We’ve never been more involved with our screens, but is the relationship a healthy one?

As I sit down to write this piece, my smartphone is in the next room, timed to remain silent for 45 minutes, during which I don’t want to move away from my writing desk. My writing document is offline, and my mind wandered for ten minutes before I could write the first version of this sentence.

‘Lock your phone away’ is a common productivity hack that I baulked at until I looked at the screen-time analysis on my phone for this story. It seems I check my phone 139 times on average every day. This number is much lower—by a fourth—on days when I have social engagements or a project that doesn’t include gadgets, such as my weekend meal prep or cleaning. Most other times, I have to stay away from my phone physically to avoid being distracted.

All the books and research I’ve read on the subject assert that this is not a feature of a weak will; it’s only our primal response to a cleverly designed reward system. Our phones are to us what food was to Pavlov’s dog.

In 2020, of the 749 million internet users in India, 744million are estimated to have accessed it via a mobile phone. In the same year, India had a smartphone penetration of 54 per cent. India is one of the fastest-growing markets for both mobile phones and phone data.

Smartphones and the internet are the new television. Though the ‘idiot box’ expanded the worldview of generations, we also pointed fingers at cable television for numbing our minds, making us buy things we didn’t know we wanted and making us couch potatoes. History repeats itself and we have yet another paradox—this time in our hands, and a foot away our eyes.

Screens—for those of us who have them—gave us access to healthcare services and education during the lockdown and no-contact days of the COVID19 pandemic. But does the India that attended online classes and went to work on video calls since 2020 also run the risk of losing its agency to the lure of gadgets?

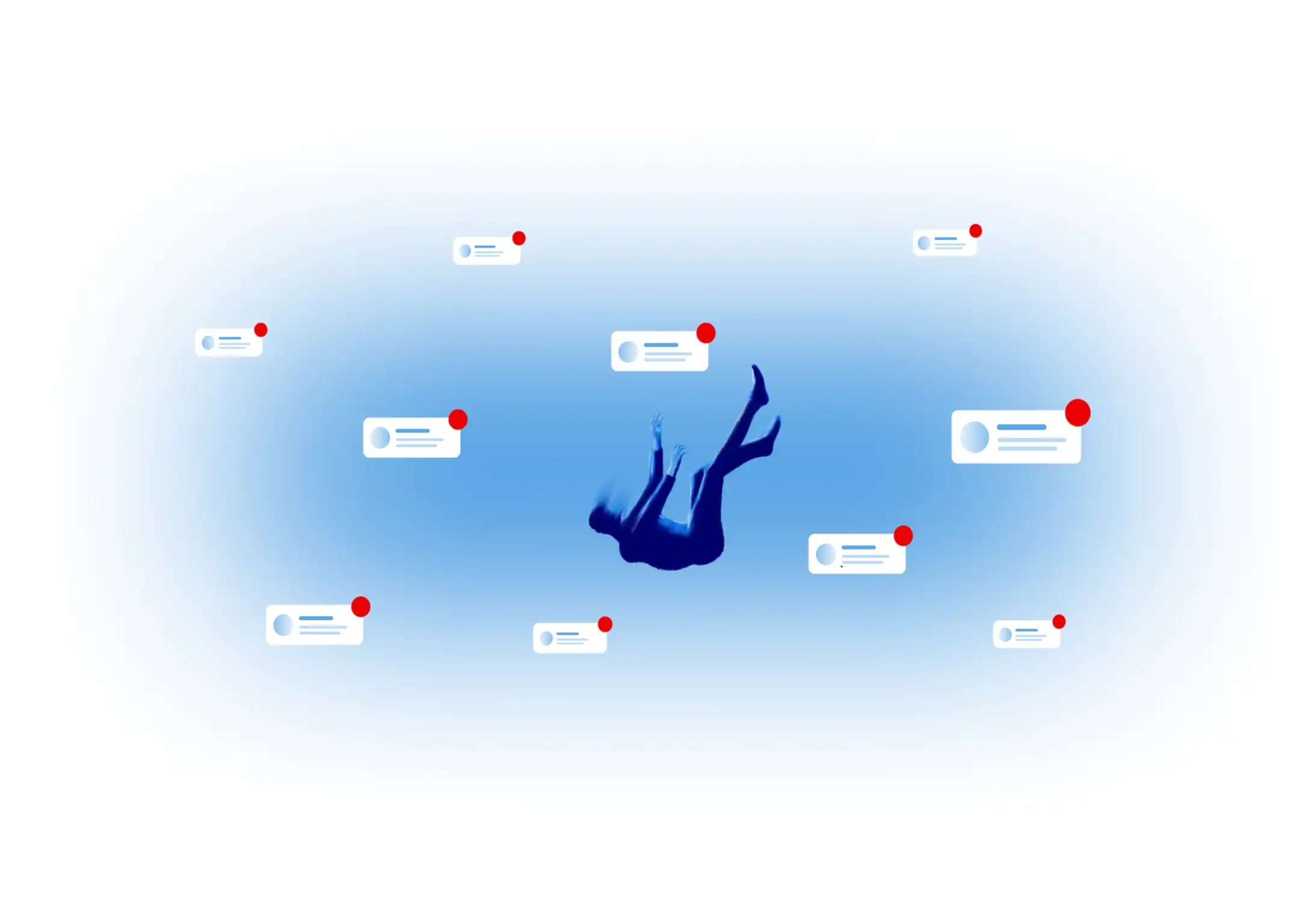

It is widely understood that gadgets are designed for stickiness, and apps and websites are designed to get our attention and turn it into advertising revenues. Clicks and bounce rates are the new circulation numbers, they all want your eyeballs, they all want your data. Attention is such a hot commodity that advertisers are willing to pay celebrities such as cricketer Virat Kohli, who reportedly charges US$ 680,000 for a single Instagram endorsement.

The first President of Facebook, Sean Parker, talked about this in 2017, “It’s a social-validation feedback loop … exactly the kind of thing that a hacker like myself would come up with because you’re exploiting a vulnerability in human psychology.” he said in an interview to Axios. The tech industry, while aware of the whirlpool, continues to gamify our experience on everything from news sites and social media to payments apps and grocery stores. The science behind this, in its simplest form, lies in understanding how habits are formed.

Habits are connected to a reward pathway in the brain called the mesolimbic dopamine system. This circuit or pathway looks for stimulants that are pleasurable, such as food, sex, substances, social interactions or alerts from gadgets and tells us to learn and repeat the actions that led us to the stimulus. We then memorise the series of behaviours and act to automatically seek the same rewards. It’s a pathway that was perhaps created to help us seek food and sex for survival without great cognitive load.

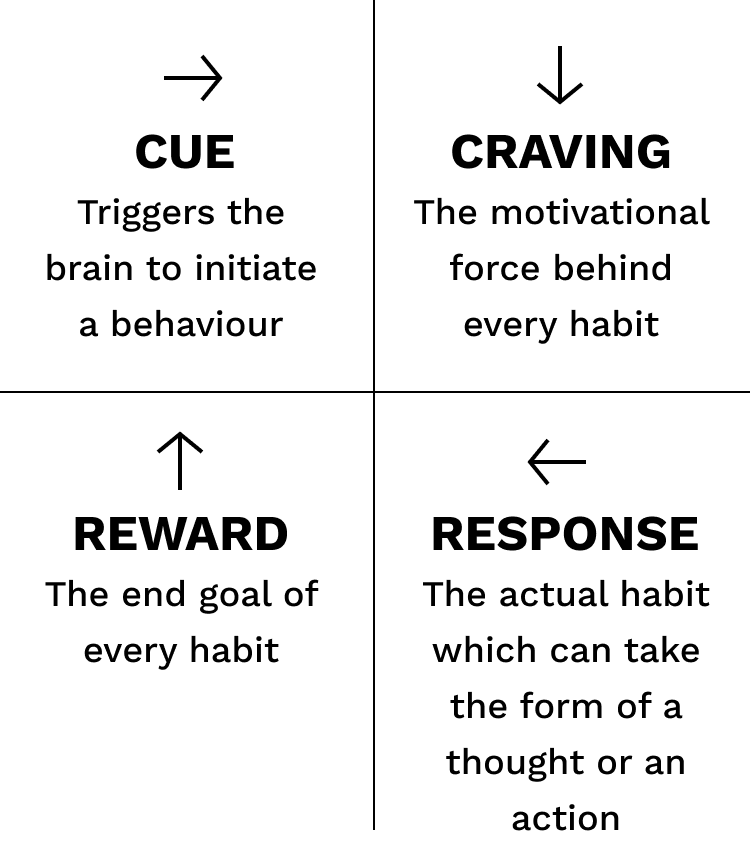

When we repeat any behaviour several times it forms a neurological loop that doesn’t take deliberate effort every time we perform it. This applies both to good habits and bad ones. James Clear in his now widely popular book Atomic Habits talks about the loop. “ In summary, the cue triggers a craving, which motivates a response, which provides a reward, which satisfies the craving and, ultimately, becomes associated with the cue. Together, these four steps form a neurological feedback loop—cue, craving, response, reward; cue, craving, response, reward—that ultimately allows you to create automatic habits. This cycle is known as the habit loop.”

If you think about your behaviour, there is always a cue that triggers a craving. If you light a cigarette, or pour out a cup of coffee as a response to a stressful situation (cue) a few times and feel relieved after the first puff or sip (the solution), you then look for a cigarette/ coffee when in a stressful situation or expecting one. The same applies to the ping of a smartphone notification: You remember the dopamine release you felt when you last checked out a ping. Ping (cue) – craving – response (pick up the phone) – reward (dopamine release from seeing a new email/ like on a social media post).

The Problem Phase

CUE

Your phone buzzes with a new text message.

CRAVING

You want to learn the contents of the messages.

Solution Phase

RESPONSE

You grab your phone and read the text.

REWARD

You satisfy your craving to read the message. Grabbing your phone becomes associated with your phone buzzing

Repeated behaviour becomes encoded in the brain: When you start to feel a compulsion to engage in a behaviour while being aware of its negative effects, you may have crossed over to being addicted.

Are we all addicted?

The short answer is, no. Addiction is a pathological dependence on a substance that has a significant effect on your day-to-day life. The keywords are dependence and compulsion. For the most part, most of us don’t struggle to keep away from our screens when otherwise engaged in fun and flow inducing activities.

But we are using our screens more every year. According to numbers crunched by the State of Mobile by App Annie, Indians spent over 4.7 hours on their mobiles in 2021 versus 3.7 hours in 2019. India also ranks second in downloads growth with 26.6 billion downloads of the combined global aggregate of 230 billion downloads globally.

Mobile usage data like this often don’t represent rural areas and there’s only anecdotal information to see how see how rural India compares to its urban counterparts. Nonprofits working in rural India struggle to provide digital access to their rural beneficiaries, and even more so to women.

In a survey conducted by GraamVani, on the impact of the lockdown on children’s learning, of the 1243 only 17% of parents said that they have separate smart phones with internet for their children to do online classes while 20% said that their children share the smart phones among themselves to undertake online classes. Around 55% of parents said that either they have a single smartphone in their houses for daily use or there is no smartphone. This affects their children’s education. However, even with the low usage number, 8.8 per cent of the sample size said that “the most severe adverse effect of not being able to attend school” was that children ended up spending too much time on smartphones and games.

We could well wave this away as parental apprehension but the numbers at NIMHANS’ SHUT ( Service for Healthy Use of Technology) clinic, the only clinic in the country to exclusively treat digital addiction, tells us that more people are crossing the threshold of what constitutes an addiction. The clinic now sees 12 -14 cases per week compared to 8 per week before the start of the pandemic “ Most of these cases are of people who are addicted to gaming and pornography. Gaming among adolescent and young adults and pronograpghy among adult men,” says Dr Manoj Sharma, professor of clinical psychology, who runs the clinic. The cases at the clinic are mostly from urban India.

“Since families are now in closer proximity to each other than ever before, they are getting a chance to notice excessive phone use in each other,” says Dr Sharma, adding that the need to be online constantly for work and academic commitments left no time for physiological needs such as sleep, exercise and healthy meals and created the dependent behaviour.

The data corroborate this. In a study conducted by App Annie, Indians took the top spot in missing meals to play games. We are at par with the global average of hours spent gaming (India reported 6.35 hours vs the global average of 6.33 hours). Around 57 per cent of those quizzed say they play games during their working hours.

Dr Sharma also talks about emotional distress, which often triggers addictive behaviour. “Adolescents feel that their parents don’t understand them and veer towards games and social media where they can interact with their peers and feel like they belong. In some cases, this becomes a way to escape emotional distress that they may be experiencing in their real life.”

In 2015, N, then a first-year student of engineering, recalls being in a flux, stuck with an academic course that did not excite him. A high-achiever throughout school, N found himself uninterested in the subjects being taught. “I have always been interested in Computer Science but had opted for electronics and communication without fully understanding what course details were. When I started attending college, I felt like the people around me hadn’t advised me well and I felt stuck. Instead of dealing with the problem, I decided to ostrich my way through it and started missing classes to start playing DotA [Defense of the Ancients] all day,” he says.

DotA is a multiplayer strategy game that N first came across when he was in Class 12. “It’s a challenging game in which you can get better and better and are matched with higher skill level players. I didn’t get this kind of immediate affirmation in academics, which was, you know, hours upon hours of not very fun work,” says N, adding that he skipped days of college to be at the gaming parlour. His teachers noticed his absence and reported it to his parents. N, who recalls this as being a turning point for him, then agreed to seek the help. Treatment included therapy and medication prescribed by a psychiatrist.

“I went back to college and did well. But I am still constantly aware of my addictive tendency,” he says. N, now 31 and a successful 3D artist, still games but never when he still has work pending from the day, and mostly when he wants to catch up with friends. “As long as I’m following the rules I have set for myself, I feel like I am okay,”

Addiction works in pretty much the same way whether to alcohol, cigarettes, gaming, gambling or our phone. Substances may have a higher biological hold over our bodies, but the rewards loop is the same. The hold of the substance apart, new treatment protocols recommend looking at the emotional health of those addicted rather than simply the medical aspect.

Author Nir Eyal talks about this in his book –Indistractable, How To Control and Choose your Life – in the context of distraction. Eyal, an expert in behavioural engineering says that the leading cause of distraction, even when we set out with a goal in mind, is often not an external trigger. Instead, it is boredom, uncertainty, fatigue, and anxiety. Our response to our emotions is what causes us to pick up that cigarette, phone or check that social media notification. The habit loop follows.

In a study conducted in 1972, the year when 13,760 enlisted American soldiers returned from Vietnam, it was established that up to 35 per cent had tried heroin, a highly addictive narcotic substance. However, in the year that followed their return, less than five per cent tested as re-addicted and around 12 per cent were addicted three years later.

“Most addicted Vietnam soldiers either gave up their narcotics use voluntarily shortly before their departure or did not revert to use after a brief detoxification subsequent to their discovery as users before departure,” wrote Lee N Robins et al in their paper to recommend that the standard method of treatment, which was forced detoxification and use of tranquillisers, to be revisited, at least in the case of veterans. Robins’ study showed that a change in environment, lower stress, and absence of associated triggers changed behaviour even where substances like heroin were involved.

The effect of screens

Are we okay as long as we’re not addicted? Addiction by definition means pathological dependence. Even in the absence of dependence, some kinds of screen usage do affect us adversely. In a significant 2019 Stanford study, 1,600 US-based students were recruited and asked to deactivate their Facebook accounts for four weeks in the run-up to the 2018 US midterm elections. This group reported a small but significant sense of well-being. While the deactivation of Facebook left them less informed of the news, they were also less polarised and found themselves spending more time with friends and family.

Closer home, in a rare community study done on the effect of screens on children under the age of five, Nimran Kaur et al from the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research (PGIMER) at Chandigarh, found that approximately 59.5 percent of children of the 400 studied had excessive screen time. Screen time was higher on weekdays (58.5 per cent) compared with the weekends (56.8 percent).

The team found that excessive screen time can have adverse effects on a child’s development: delay in language development, cognitive skills and motor skills, lethargy, impaired concentration, aggression, sleep problems and poor academic performance.

The effects are accentuated as the child grows older, with a preference for sedentary activities and hyperactivity sometimes. Following this Kaur and her colleagues also developed an intervention labeled Program to Lower Unwanted Media Screens (PLUMS) that was administered both to the parents/ caregivers and the children over eight weeks. The intervention largely included theme based activities for the children and guides for parents to involve their children in media-free activities. “We also developed a validated screening tool that paediatricians and healthcare workers can use in their clinics so they can identify excessive screen behaviour early and counsel parents on appropriate screen time ,” says Dr Madhu Gupta, a researcher in the study.

In 2020 following Kaur and team’s literature review The Indian Academy of Pediatrics (2020) released a set of guidelines recommending only one hour per day for children between 2-5 years and no screen time for children less than 2 years. But it’s not an all bleak story. Access to information and even games not only made learning easier but has also helped brain development. Despite the heavy forewarning, Kaur and the team also note this in their paper.

Game designer Jane McGonigal, who has designed a game called SuperBetter to help patients recover from concussions, believes strongly that gaming (the right amount) helps you become sharper and learn to solve problems of varied kinds. Counterintuitively, she even recommends that children be given gaming time before their homework but never before bed. “ You retain what you learn before you go to sleep, “ she says in an interview with Shane Parish for his podcast, the Knowledge Project.

On how much is too much, she says: “ So if it’s over 21 hours a week, I do recommend that you start trying to control it or shape it unless they are an extremely accomplished e-sports player.” McGonigal warns that if gameplay seems to increase in intensity while real-life problems are also increasing you need to work with them to put their attention on other things as well.

The same applies to all screen behaviour. Dr Sharma from the SHUT clinic talks about building a healthy relationship with screens. “It’s important to pause and think about how screens are impacting other areas in our lives. Screens are a necessary part of our lives today, but using them as unfettered methods to cope with stress or defocusing on other parts of our daily routine should act as a red flag,” he says.