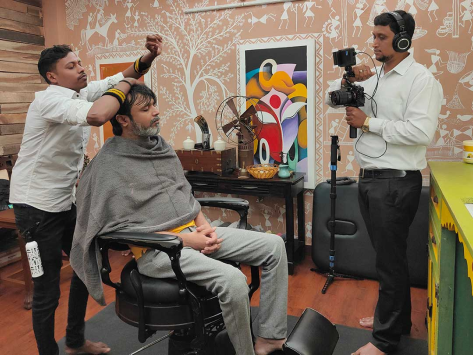

At 39, Santosh Ojha has his work cut out for him. He sits in a barber’s chair at a salon he owns and gets a head massage week after week. A videographer captures this on camera. The massage videos, skilfully shot with heightened visual and audio-sensory inputs, are then uploaded on his YouTube channel Indian Massage, where thousands of users around the world watch these massages as a way to destress. Ojha, whose vocation helps him earn roughly north of Rs. 1.5 lakh per month, runs multiple YouTube channels under the unusually popular Indian barber category.

Ojha found his calling a decade ago when on a freelance assignment for Italian YouTuber Massimo Tarentelli, who asked him to meet and film Sohan Lal Sen, popularly known as Baba Sen or Cosmic Baba, giving a head massage. Tarentelli was compiling videos of massages given by rustic, roadside barbers in hinterland India.

Intrigued, the Nagpur-based Ojha made a call and fixed up a date with Sen in the Rajasthani pilgrim town of Pushkar, a popular destination of Western tourists looking to score the local weed.

Ojha recalls meeting a short, lanky man probably in his late thirties, with a signature grin revealing betel-stained teeth and sporting a heavy mop of hair and a thick moustache, and wondering about his appeal for an Italian YouTuber and his audience.

Baba Sen was a regular among tourists, showing them around Pushkar as a tour guide or offering them a shave and a haircut or an occasional massage.

Roughly in the late 2000s, a European tourist who went by the name Christian, recorded a grainy video of Baba Sen giving him a head massage. The video depicted an animated and energetic Sen, who occasionally glanced at the camera, seemingly unsure why he was being filmed, while vigorously swaying his hands and making heaving sounds in what seemed like an attempt to ward off negative energy from a visibly relaxed Christian. It is now viewed as the origin of ASMR content from India.

Autonomous sensory meridian response, better known on the Internet as ASMR, has become an unlikely trend on social media in recent years. The term defines the relaxing sensation someone experiences when watching certain visuals or listening to particular sounds.

Relaxing audiovisuals

Over the years, like Ojha, many Indian Youtubers have found a global audience devouring videos of Indian barbers performing vigorous massages using hot oils, candles, ice, stones and jade rollers in rustic roadside salons in the plains and Himalayan mountain valleys.

Ojha, who has studied 3D animation, worked briefly as a visual artist and videographer. He worked as an animation artist at Reliance BIG and Zee Institute of Creative Art before becoming a freelance videographer and eventually a YouTuber in 2017.

Ojha has had a long journey to where he is now–he has been on numerous train trips across the country–from the Western ghats of Maharashtra to the banks of the Yamuna in the north and to the bridges of Kolkata, meeting local barbers and recording them performing energetic head massages.

“After a long day at work or classes, some people don’t want to watch Netflix or read books. That’s the space for ASMR content. It is essentially an audiovisual experience that helps people relax. You don’t need to use your mind. It’s like an adult watching a cartoon video. It relaxes you,” says Ojha, who along with Tarentelli, now his business partner, has invested around Rs. 16 lakh in setting up a studio in Nagpur to record ASMR videos.

Ojha runs multiple YouTube channels airing Indian massage videos. With one of them, Indian Massage, attracting 280,000 subscribers, Ojha says Baba Sen, who died of a cardiac arrest in 2018, started the trend of Indian head massages on YouTube before ASMR as a content category was even introduced on the Internet.

Before his passing, many YouTubers from Europe, Russia, the Middle East and US travelled to Pushkar to shoot videos of Baba Sen performing massages. It has helped their YouTube numbers so much that many of them made repeated trips to Pushkar to shoot videos with Sen, says Ojha.

Even after his death, his videos remain insanely popular, attracting millions of views. The popularity of Sen lifted demand for Indian barber massage videos among ASMR consumers globally.

Hundreds of channels exist in the Indian head massage ASMR genre with YouTubers hunting down local barbers in all parts of the country, planting their expensive mics and cameras at the roadside salons and tipping barbers for performing massages on camera.

From neck cracking to scalp popping to using props like chopsticks, rolling pins and even fire for pain relief, Indian massage ASMR content on YouTube is sold to Westerners as a cheaper and healthier alternative to sleeping pills.

Is this for real?

When I first observed the trend on YouTube and reached out to Ojha through his Instagram page, he asked me to send a list of questions to set the context for our conversation. Among other things I was curious to know who watches these videos. Is his audience regular people browsing the Internet for entertainment or oddballs looking for weird content on YouTube?

“Our audience is different,” Ojha responded to my question through Instagram. “Some of them are students in the middle of exams. Some are mothers looking after their newborns. A few are racetrack drivers preparing for the next competition. They are all looking for a way to unthink for a while so that they can fall asleep,” he wrote.

These videos are generally shot in a soundproof room to minimize unwanted sounds. The focus is to create a heightened audio-visual experience for a viewer by highlighting sounds that are termed triggers in the ASMR context.

For example, scratching of the head, tapping of fingernails, the sound of soapy foam when it’s lathered on skin with a shaving brush and so on. It’s almost as if the barber is creating a massage experience for the mic and camera more than the person on the chair.

Warm and tingling

Consumers of this content often ask Youtubers to use certain sounds in their videos that work as triggers for them. Often described as a warm and tingling sensation that starts on the scalp and moves down the neck and spine, there are many sub-genres in ASMR. Head massages, whispering, role-playing and chewing sounds while eating aka mukbang (in Korean) are some popular sub-genres of ASMR on YouTube.

“Different people have different triggers,” Ojha tells me a few weeks later over a phone call. He opens up about his experience in creating, understanding and eventually becoming a consumer of such content.

“Even though I filmed and watched a lot of barber massages as a part of what I do, it didn’t work for me personally,” he says. “I later found my trigger while watching construction ASMR, like the sound of cement mixing with water. That helps me relax and fall asleep.”

But how does a video played on a screen aid in someone relaxing and eventually falling asleep? I ask Ojha, still skeptical about the appeal of such content.

“Have you never fallen asleep while watching TV? That’s unintentional ASMR. The sounds get monotonous and help you relax and calm,” says Ojha, adding that many people need sounds of trains, buses or river streams because they are used to sleeping to those sounds.

Newborns need white noise that replicates sounds inside the womb, helping them relax and sleep. This isn’t much different except that it is intentional ASMR. These sounds are deliberately created to replicate an experience that helps calm a viewer down.

What is ASMR?

According to various sources on the internet, ASMR, which sounds a lot like a clinical term, was born and christened on the Internet by Jennifer Allen, a cybersecurity red teamer. Allen, who recalls looking up a term to describe the sensation of tingling spreading through the scalp repeatedly, found her tribe on a message board forum titled “WEIRD SENSATION FEELS GOOD.”

People on the forum were thrilled to find others like them who had experienced similar “brain tingles” and voiced the need for a community. Allen then founded a Facebook page for this community and also coined the term autonomous sensory meridian response.

Over the years, the thread grew to have thousands of replies from people describing the sensation as a euphoric feeling of tingling mostly triggered by external factors like someone talking in a hushed tone or watching someone paint. A majority of the people on the forum said the feeling is triggered when someone is focusing on a task 100 percent for you.

Craig Richard, professor of biomedical science at Shenandoah University in Winchester, Virginia,. and author of Brain Tingles, a book on triggering ASMR for improved sleep and stress relief, equates the tingling sensation caused by ASMR to frisson, a brief sensation often manifested physically in the body in the form of goosebumps or chills.

Hormonal release

“Many people first experience ASMR by accident through a hairdresser or a soothing teacher or a grandparent through their caring and gentle mannerisms,” writes Richard in his book, adding that many ASMR triggers, like whispering or brushing of the hair or petting a dog are synonymous with receiving personal attention from a caregiver.

Activities like someone speaking to you gently, touching you lightly, reading to you, sharing a story with you or brushing your hair may stimulate the release of oxytocin (the hormone that causes a surge of positive and happy emotion) and therefore the feeling of relaxation, notes Richard.

“Though you are not a cave person whose life is being threatened, there are times in modern life where you need to trust certain strangers in situations in which you are vulnerable—like a visit with a masseuse, a therapist, a clinician, or a scissor-wielding hairdresser. Their expertise, professionalism, caring nature and gentle personalities seem to be the core traits of an ASMR-stimulating disposition,” says Richard.

This explains the popularity of barbers like Baba Sen or his successors or all those young women who talk into their mics by making eye contact with their viewers and whisper caring phrases into headphone-wearing viewers, gently wheedling them to sleep through personal attention and familiar sounds.

Nurturing social interaction

In 2018, Giulia Poerio, a University of Essex researcher and Google scholar performed a study on 112 participants (half of whom said they experienced ASMR) and hooked them up to electrodes to observe how their bodies reacted when they watched their preferred ASMR videos.

While watching the videos, participants’ heart rates fell – a sign of relaxation. But they also perspired more, indicating heightened emotional arousal, noted Poerio in the results of her tests.

In another study by Richard conducted in the same year, participants watched ASMR videos while undergoing MRI scans of their brains, pushing a button inside the MRI scanner to let the researchers know when they felt relaxed or had tingles.

The study indicated that ASMR tingles lit up many brain areas, including ones that process reward, emotional arousal, and social behaviour. It also indicated activity in the medial prefrontal cortex, the hub of the brain’s social network. Evidently most ASMR videos on YouTube also fulfil the basic requirements of nurturing social interactions: giving personal attention, talking gently or whispering and focusing on a task at hand with utmost attention.

Freelance writer Aatmajyoti Aarya, who first experienced ASMR when she was 29, describes the experience as the “opposite of stimulating.” Single monotonous sounds like those made by makeup brushes on the skin or the sound of paintbrush on canvas helped her calm down when she felt anxious.

“It’s a gradual process but I could notice changes in my body. Within 15 to 20 minutes into an ASMR video, I could feel my shoulders relax and my head feel lighter,” says Aarya, who has also sought guided meditation in the past to help with her anxiety.

Though she doesn’t recall experiencing unintentional ASMR, Aarya says there’s a treasure trove of content on YouTube, carefully curated to enhance the viewing experience.

Pop culture movement

In the last decade or so, ASMR had its own pop culture movement with celebs like Ashton Kutcher and Gal Gadot participating in it to brands like Dove, Pepsi, KFC and Sony creating ASMR-inspired commercials.

Food bloggers on Instagram often resort to sound-induced triggers like chopping, grating and water pouring, borrowing pleasant audio cues from ASMR creators aka ASMR-tists.

Evidently, a lot of ASMR consumers go on to become ASMR-tists and creators on YouTube. Twenty-year-old business administration student Devya Gurjar says that she discovered makeup ASMR videos on Instagram during the first COVID19 lockdown. They helped her sleep. Gurjar who was always fascinated by YouTubers, started her own channel, Devya Gurjar ASMR, where she now posts personal attention videos, where she uses role playing, whispering and nail-tapping among other triggers for her videos.

“The overall awareness or understanding of ASMR in India is still at an early stage,” says Delhi-based Gurjar, adding that a lot of people who watch it the first time may find it strange.

Ojha says that even though there’s very high demand for Indian barber’s massage content in the ASMR genre from India, the majority of the viewers are based out of India.

Most of his audience is in the US and European countries, where stressed Internet users log in, usually late at night, to watch Indian barbers perform tranquilizing massages that soothe them into slumber.

YouTuber Santosh Ojha in the barber’s chair with barber Vikram Nandurkar doing a head massage

Ojha’s studio in Nagpur— a joint investment of Ojha and Italian YouTuber Massimo Tarentelli

Behind the curtains, camera and mic

It is July; months after Ojha and I first interacted on Instagram. I’m at his studio, a quiet room behind a regular salon that keeps Vikram Nandurkar, his payrolled barber, occupied when they’re not shooting videos. Ojha has half a dozen barbers who shoot for him regularly or drop by when they need to make an extra buck.

The studio has a very well-lit false ceiling needed for visual appeal and even lighting during recordings. The walls are an undertone of solid brown with white Warli paintings on them. The ceiling fan is conspicuously absent. There is an air conditioner for when it gets hot. On an average the summer temperatures can soar upto 45 degrees in Nagpur. An antique metallic table fan and gramophone placed on a solid wood table add to the overall ambience of the room.

Besides being very artfully designed, the studio is soundproof like a black box. A wall of the studio is plastered with cured wood to muzzle outdoor sound while keeping the aesthetic intact. There’s a dehumidifier in the room to prevent the wall and the wooden floor from moisture damage.

The main piece of furniture in the room is the wooden green and yellow mirror shelf that has a host of oils, soaps, brushes and massage props like rollers of all shapes and sizes, stones and wooden hammers on display.

Ojha explains how every prop and instrument on the shelf is almost a collectible item—either handpicked from a shop or imported from another country. For example, finding a straight razor in India was quite a task a few years ago. So he got one from Germany. There’s a honing stone for sharpening these razors, almost a vintage item for salons these days. Shaving brushes with real badger hair sit on the top shelf adjacent to the mirror. While faux badger hair brushes are sold online for under Rs. 500, the real ones can cost upto Rs. 13,000. The most expensive brush in Ojha’s studio is worth Rs. 9,000.

How would his audience watching these instruments on screen know the difference between a real or fake badger hair brush, or why would he need a straight razor for that matter, I ask him.

“People watch our videos for the experience,” Ojha says. Straight razors that have recently been replaced by the use and throw ones add to the authentic experience and old world appeal. The kind of lather a real badger hair brush can generate cannot be matched by a fake one, he says.

“Because people are in this for the visual and audio triggers, these authentic tools can enhance the overall experience,” says Ojha. His studio is a classic example of creating an old world experience for new-age users seeking comfort in authenticity. Ojha’s team also records videos for Tarentelli’s channel The Quiet Barbershop in this studio.

The shooting equipment, including the cameras and mics cost up to Rs. 4 lakh and require frequent repairs, maintenance and replacement due to wear and tear, says Ojha. The barbers also need to be educated in terms of what works well on the camera, what can be called triggers and what viewers are looking for. These are new skills for them that sometimes can be daunting and have a steep learning curve.

“Are you aware that barbers in ancient India were traditionally used as messengers, mediators and even confidants?,” Ojha informs me as his team of a videographer and barber prepare for a recording session.

When you sit on a barber’s chair, your neck and guard down, it leaves you exposed and vulnerable to a scissor-holding barber. Naturally, this is a relationship based on trust.

Fear of technology

Ojha says that Baba Sen, Nandurkar and almost all barbers he’s worked with come from a family line of barbers with the profession now evolving to the men’s grooming industry that we see today.

And even though the demand for Indian barbers on YouTube has shot up in the last few years, there are hardly any barbers who run their own channels.

“There is obviously the fear of technology and learning how to shoot, edit and upload videos that holds back barbers from getting into this. Also keeping up with the YouTube algorithm isn’t exactly a linear learning process,” says Ojha, adding that Baba Sen himself never had his own channel, until a Youtuber helped him set it up.

The channel had a few videos and eventually fizzled out before it could be monetised. In fact, even though Sen helped many YouTubers globally in raking up their numbers and income via YouTube, he died in massive debt. Sen’s older son Rohit Sen, known on YouTube as Baba Sen Junior, now runs the barber shop and is also sought out by YouTubers to record his massage videos.

“My father was probably the most famous barber in the world but when he died he only had Rs. 4,000,” says the 29-year-old junior Sen. Despite knowing the challenges of being an Internet-famous barber, Sen says he hopes to continue his father’s legacy on YouTube by posting his father’s old videos and his new videos on it.

The ASMR market on YouTube, though niche, has evolved quite a lot in the last few years. Ojha recalls recording his first ASMR videos on a Samsung S7 phone with a 12 megapixel camera. Competing with developed country YouTubers like those from the US and Israel, the video and audio equipment have to be at par with theirs and require a massive investment today, says Ojha.

Barber Nandurkar ready to perform a head massage for YouTube viewers

The barber’s cut

The unspoken agreement between a barber and a YouTuber or videographer who records a barber is to tip the barber “handsomely” after the shoot. Ojha says that initially he’d pay a barber a 100 percent tip; so for a haircut and massage that cost Rs. 100, the barber would end up getting Rs. 200. Later, when he developed a relationship with a barber or the barber became a regular, he also helped them whenever they had big expenses like a medical emergency or a wedding in the family.

Ojha admits to the discrepancy between the money a YouTuber makes versus the percentage paid to the barber.

The profession of a barber by itself doesn’t pay much but when the act is scripted, recorded and amped up on the Internet it can completely flip the monetary value of it. A head massage by Nadurakar in his salon costs Rs. 100, but a massage he performs in the fancy studio designed and built by Ojha, when uploaded on his channel with 280k subscribers, in tune with YouTube’s latest monetisation algorithm, can probably make up to Rs. 50,000.

“In some countries like Israel there are barbers who have upskilled and become YouTubers. But Indian barbers still have a long way to go. Unfortunately life hasn’t really changed for them despite this trend,” says Ojha.

Nadurakar smiles and nods in agreement. He is now ready to roll. Ojha gets on the barber’s chair as Nadurakar rolls up the sleeves of his white shirt and pulls up armbands on both his arms. He fixes a wrist mic on each of these bands and plugs a spray bottle on his trouser pocket. The videographer holds the camera in hand and exchanges a look with Nadurakar.

The camera starts rolling and Nandurkar breaks into a gentle smile. He puts a towel around Ojha, who rests his head on the chair and closes his eyes. Nandurkar flips the bottle, which contains water, from his pocket and sprays it on Ojha’s head – Whoosh, Whoosh, Whoosh, Whoosh, Whoosh…