The 300 million Indians older than 60 years by 2050 will owe it big time to a team of scientists, psychiatrists, and local health professionals in Kolar today. It is prospecting for gold of a different kind: data on how Indians grow old.

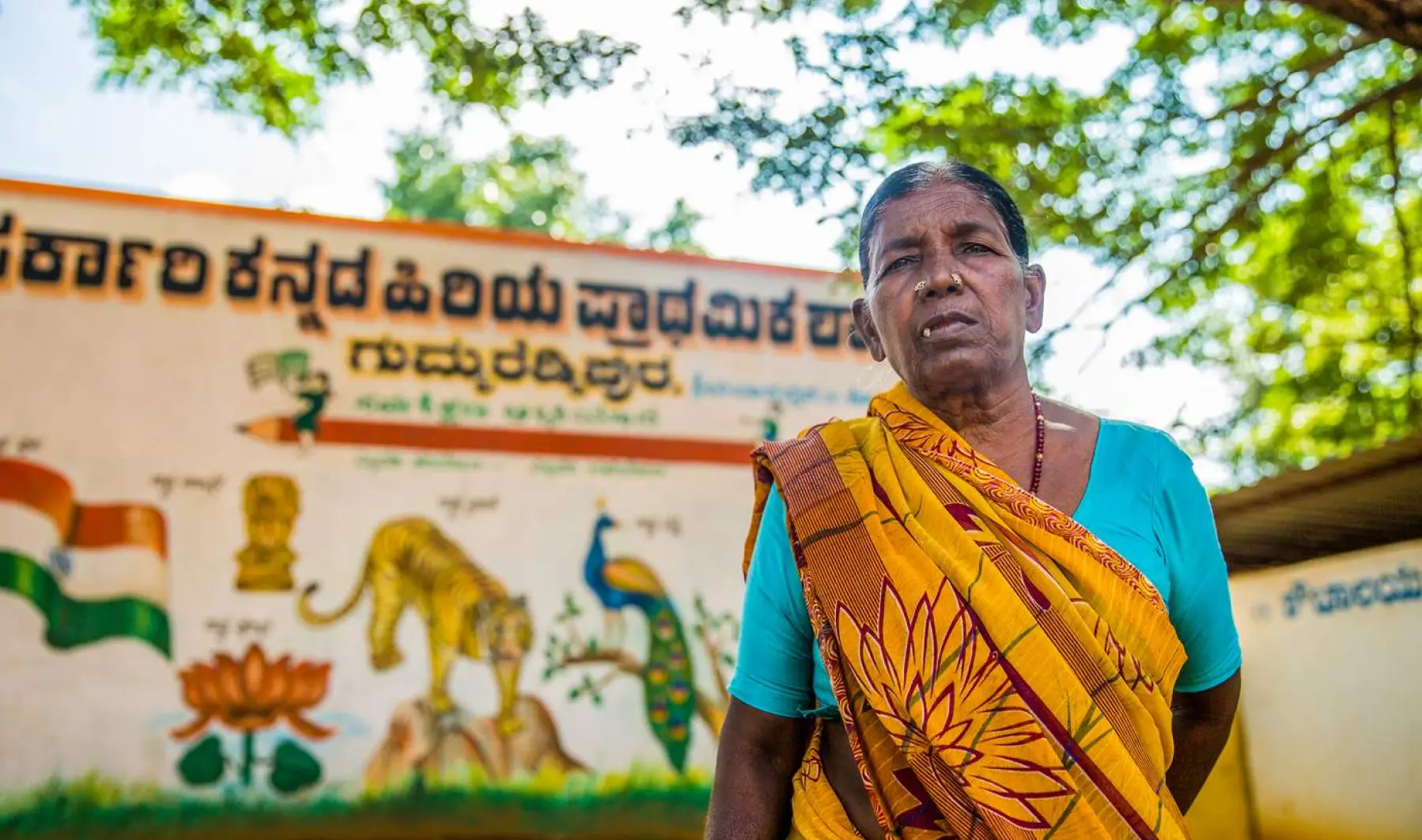

It’s a dry and nippy Monday morning in Dalasanur, a village in Karnataka’s Kolar district some 100 km east of Bengaluru. Seethamma and Rama Reddy amble into the no-frills government primary school, followed by some 30 other elderly people. Their weather-beaten, wrinkled faces tell us they are all at least 60 years old – some are limping with the help of walking sticks.

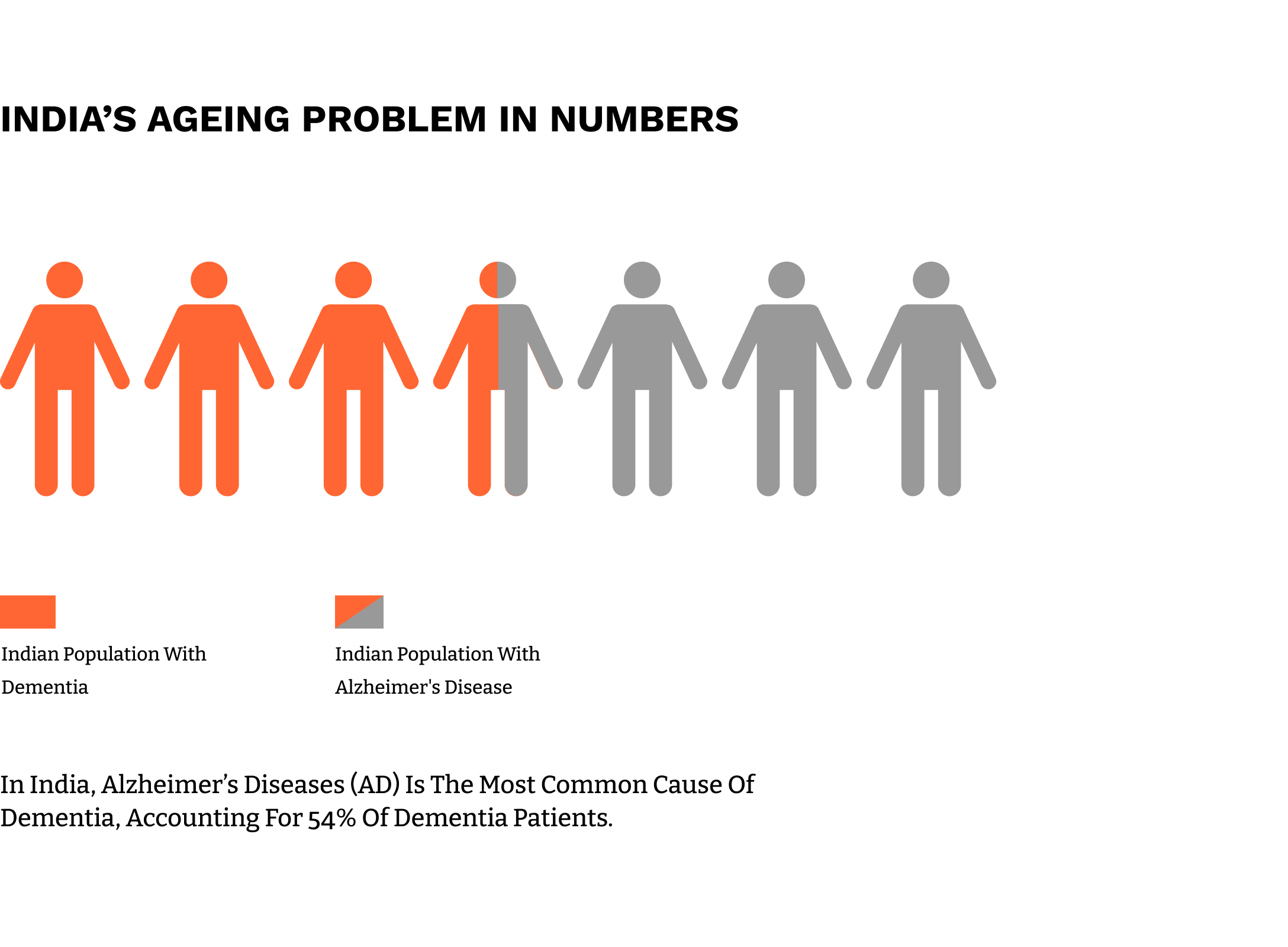

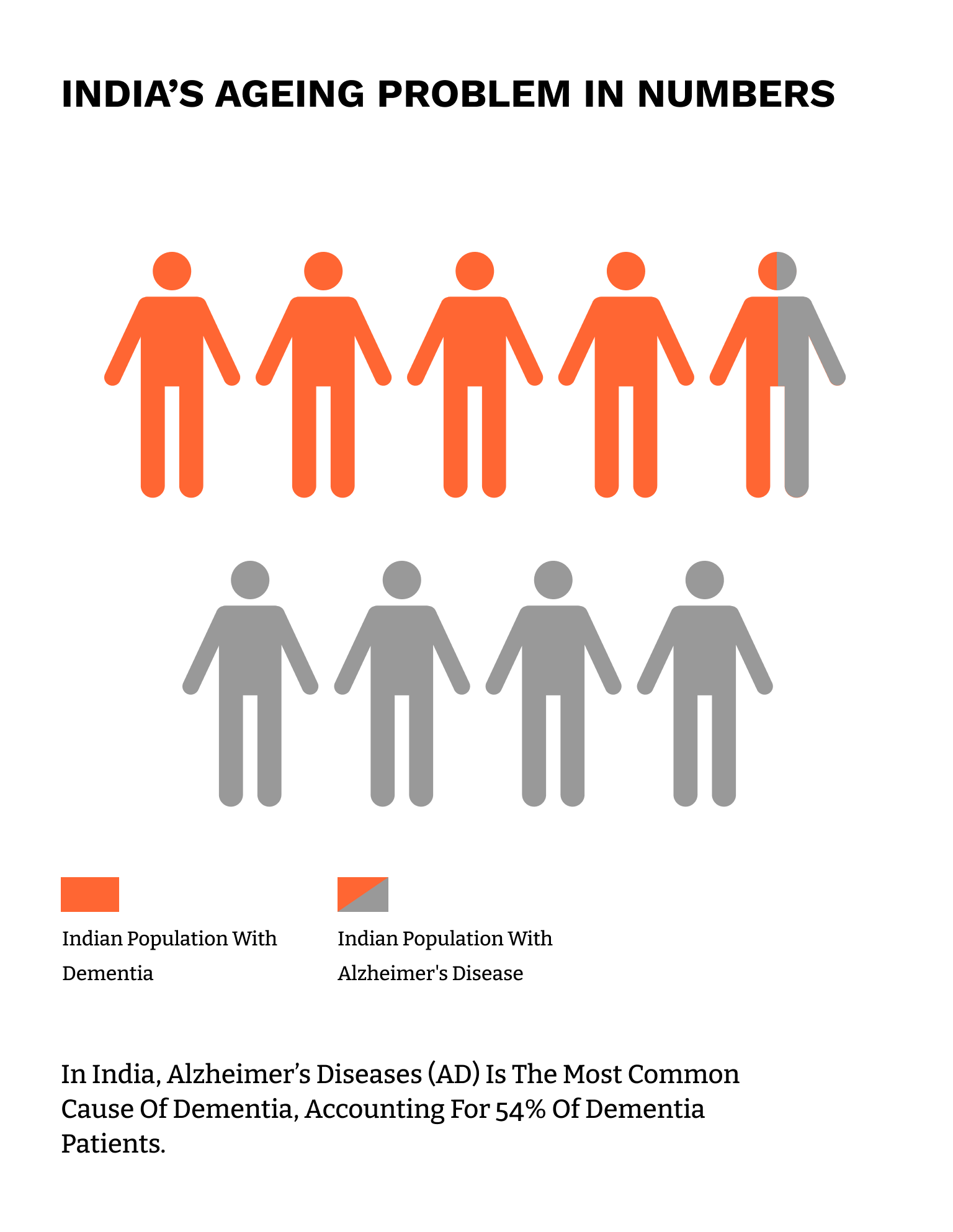

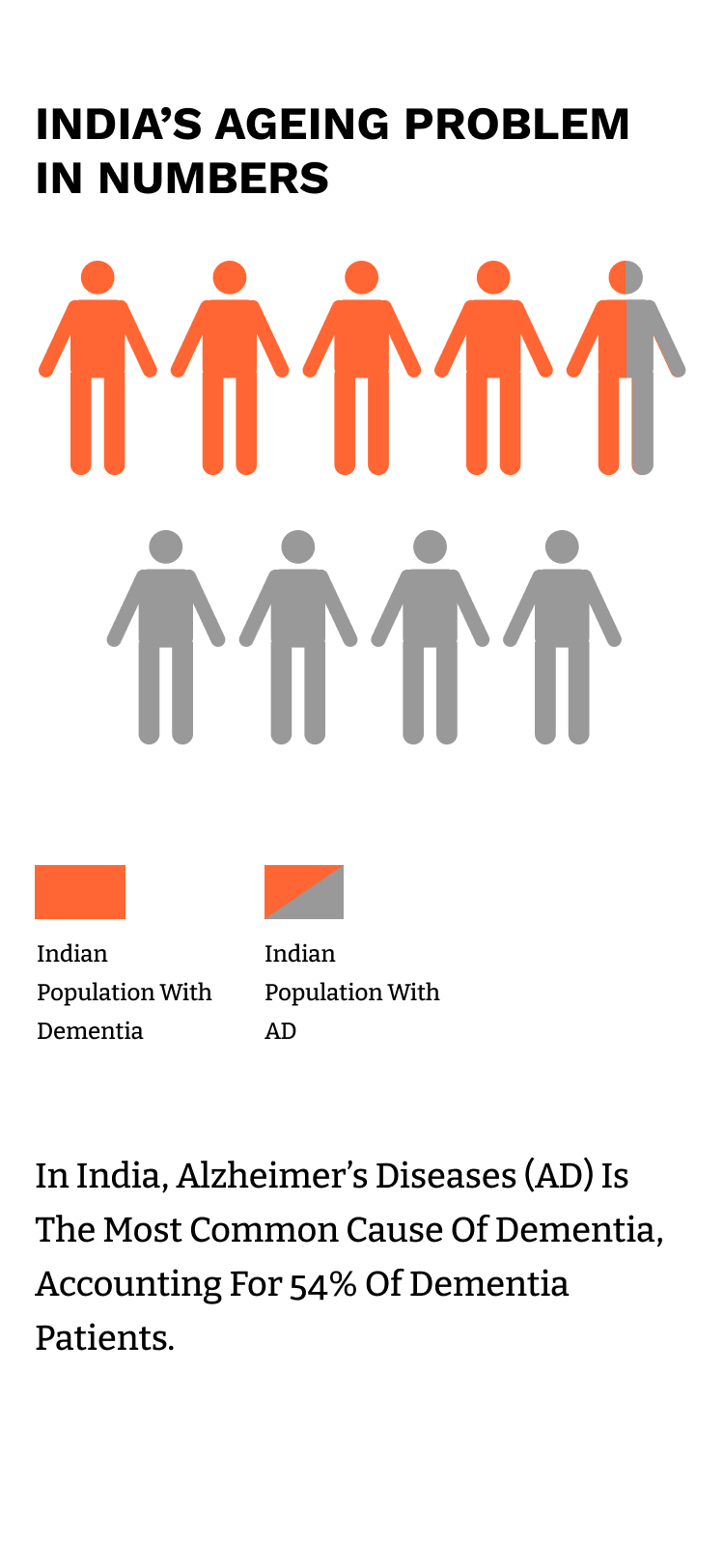

Most of them can’t even tell their exact age. In fact, Seethamma cannot even remember the names of her grandchildren. It is likely, she, along with others in the cohort, is suffering from dementia, a brain condition often linked to ageing that shows up in a host of symptoms like a decline in memory and other thinking skills which eventually lead to impairing daily normal lives. Or, even the incurable Alzheimer’s disease, the most common cause of dementia, accounting for over half of the over four million diagnosed dementia patients in India.

The school compound is buzzing with the chants-like sound of children memorising math tables.

Seethamma and others in the cohort aren’t here for any memory lessons. They are all part of a decade-long programme to capture demographic, health, brain and behavioural data of 10,000 people across 23 villages in Srinivasapura taluk of Kolar district starting with Dalasanur, Thernahalli and Chaldignahalli.

A first-in-India project in Srinivasapura? For a research cohort in a study like this to deliver long-term value, it’s crucial to identify a place where migration isn’t high. Srinivasapura with its mostly non-migrant population tending to its mango orchards was ideal for the study. This rural-focused approach comes from learnings in an earlier, somewhat similar program funded by the Tata Group, which had focused on a small, urban cohort in Bengaluru and Hyderabad and faced problems over migration.Backed with a Rs 220-crore grant from Senapathy ‘Kris’ Gopalakrishnan, the Centre for Brain Research (CBR) at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) has kicked off the programme. From Fitbits to sensors and on the ground volunteers, the program will focus on primary data collection. After that, a team of data scientists led by Bratati Kahali, a Michigan State University Ph.D., will sift through petabytes of data and come up with algorithms to help predict ageing related disorders early.

The going-cuckoo risk

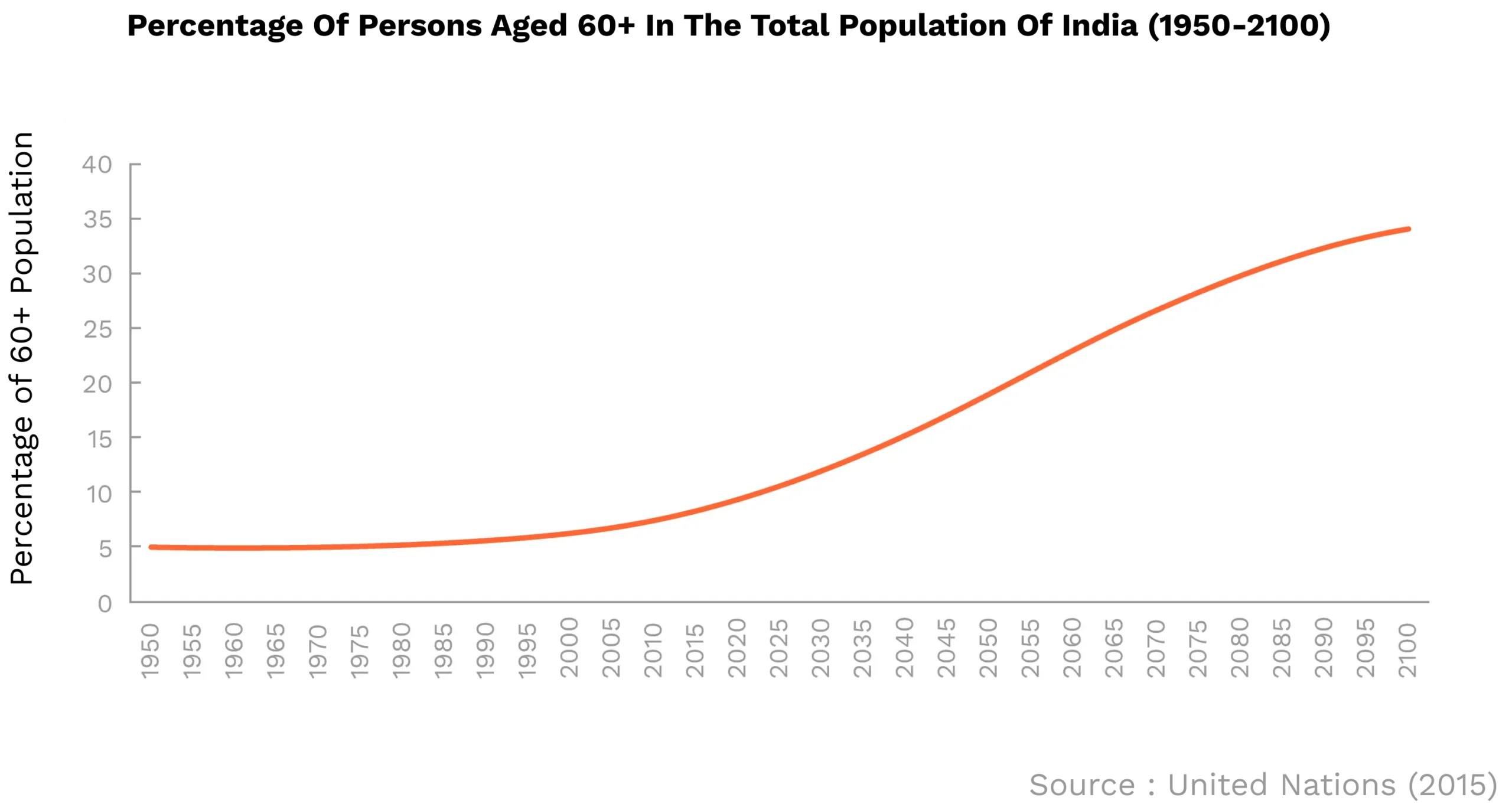

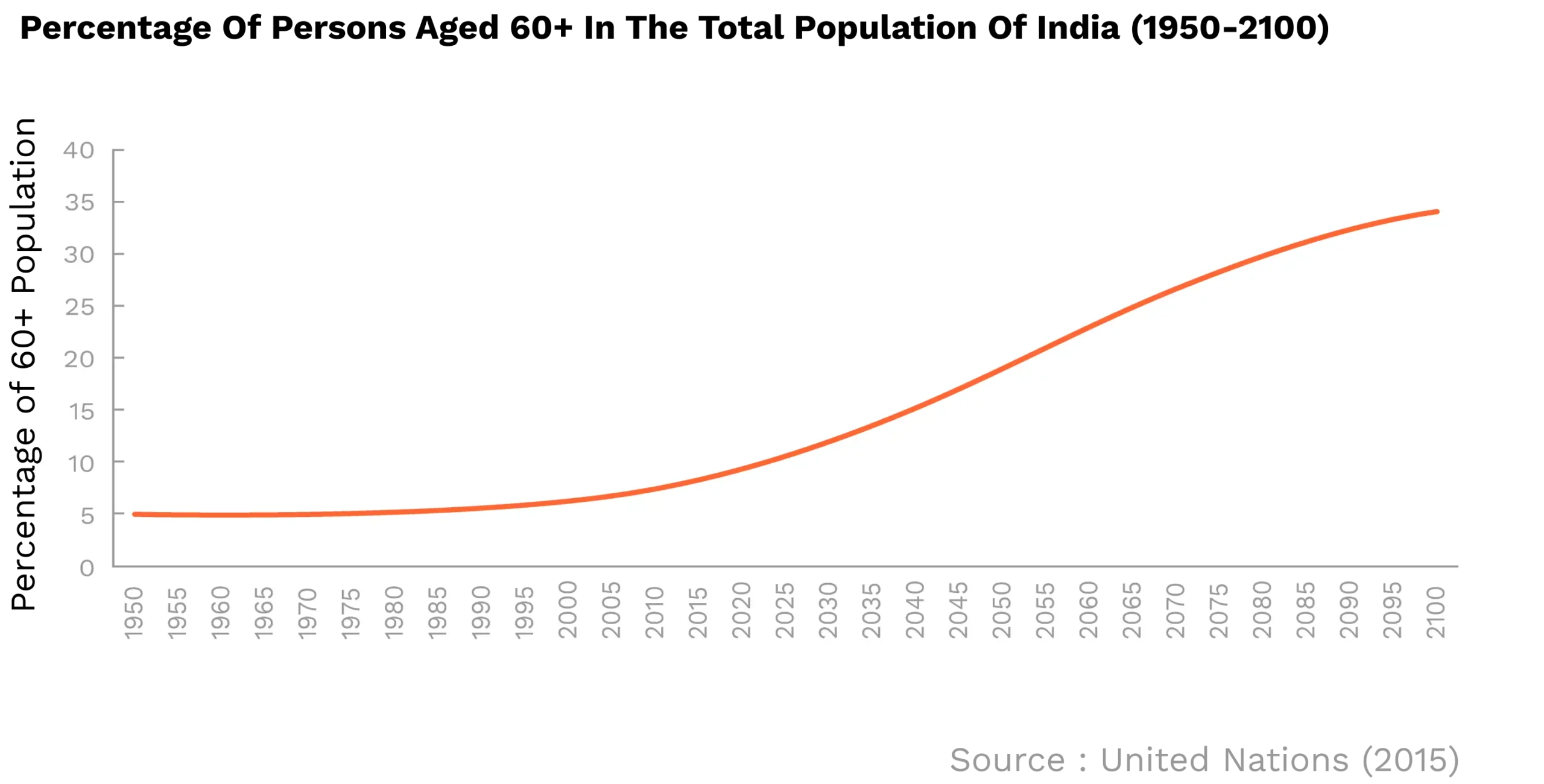

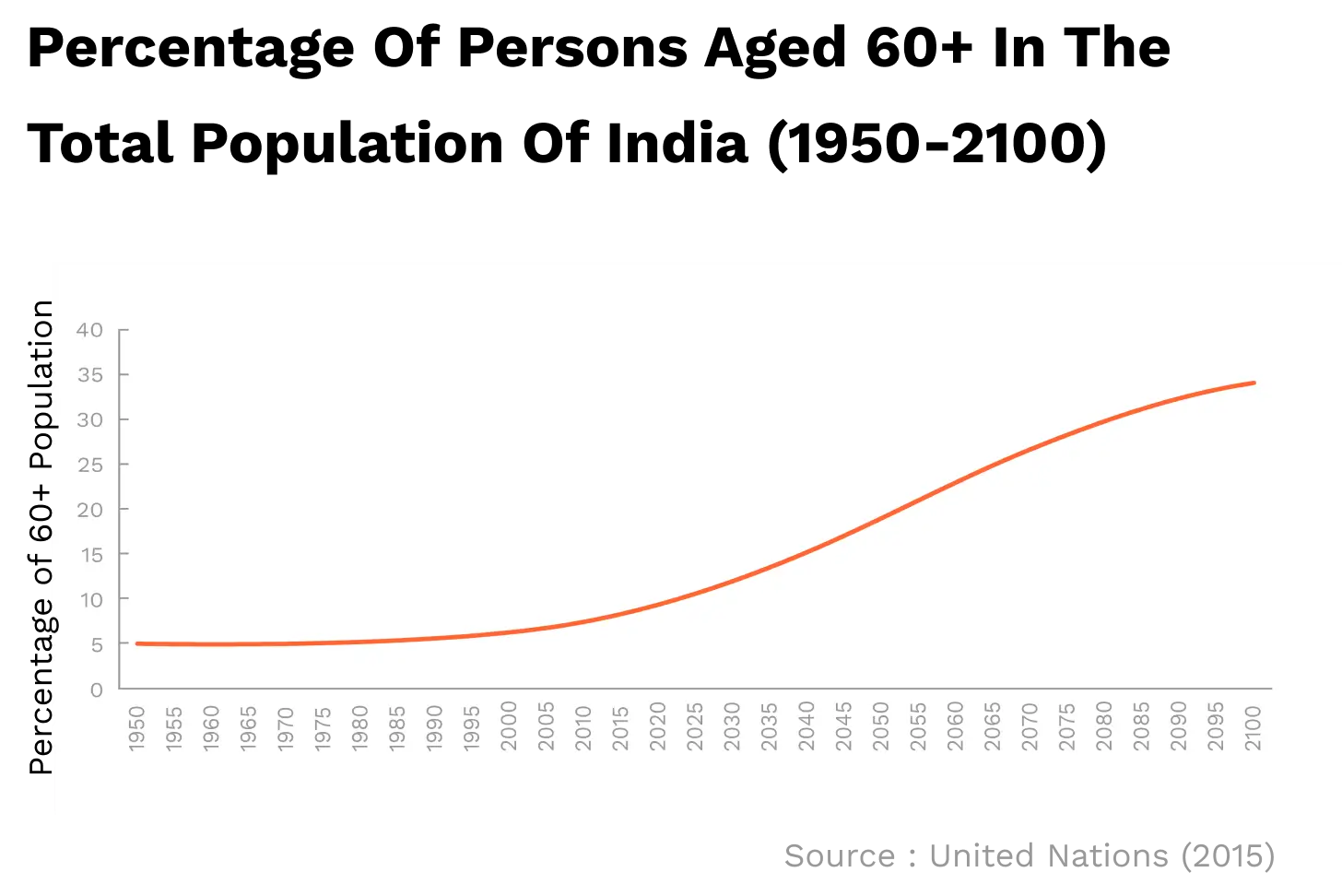

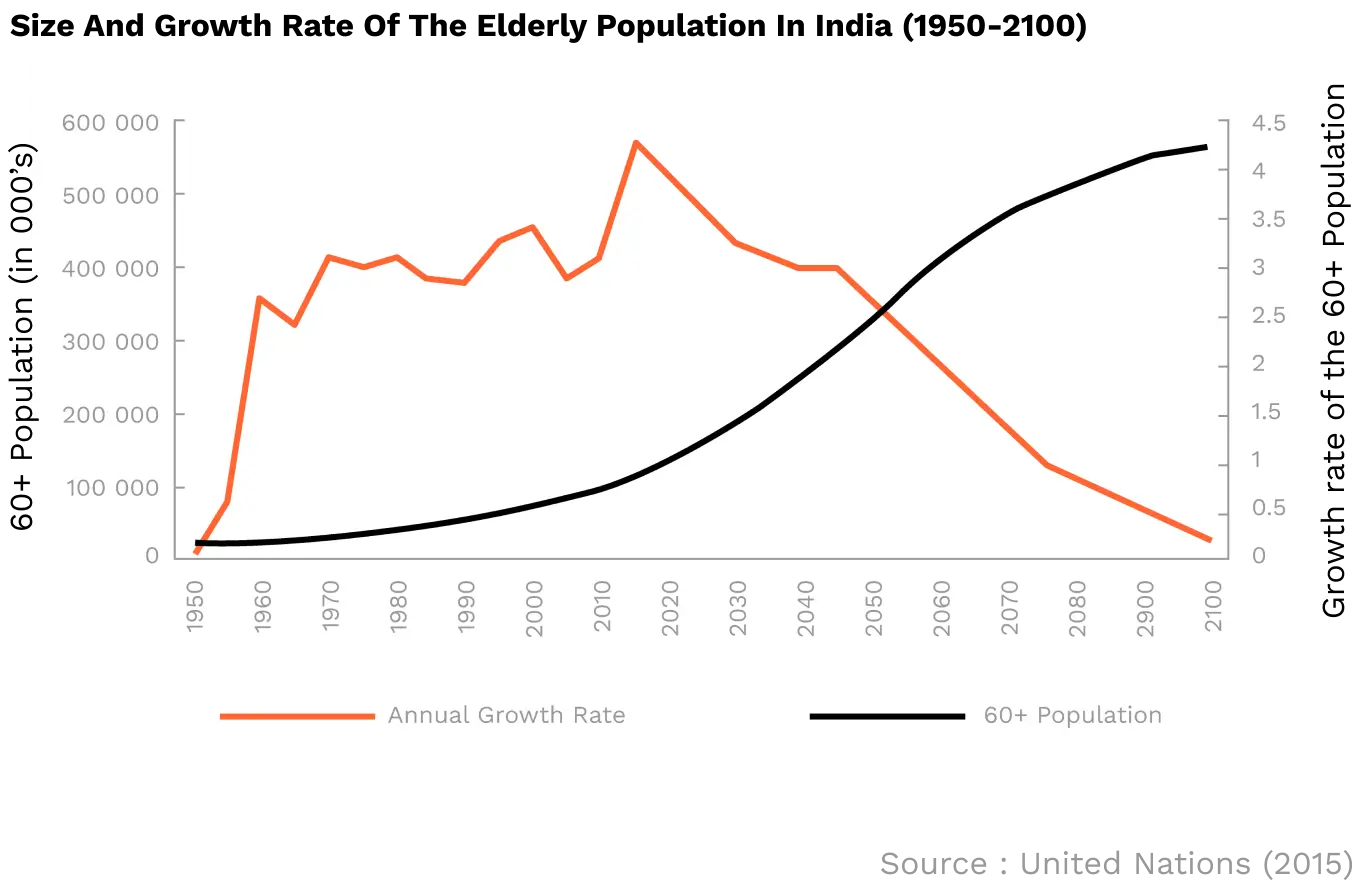

One trend is important to point to here: India’s population bulge in the middle today – two-thirds of 1.3 billion Indians are younger than 35 – will change rapidly in another three decades. UN data projects one in six Indians will be over 60 years come 2050, up from about one in 20 about 25 years ago. That’s a dramatic transition in the world, especially if you consider that India will overtake China’s population in less than five years from now. More on Indian demography later.

But why the focus on mental health? CBR sets the context: “…we need to understand the normal aging process in the brain, which often results in a decline of specific cognitive functions, heterogeneously in the population. Such an understanding can help promote normal aging and delay dementia, which is important considering the increasing life span.”

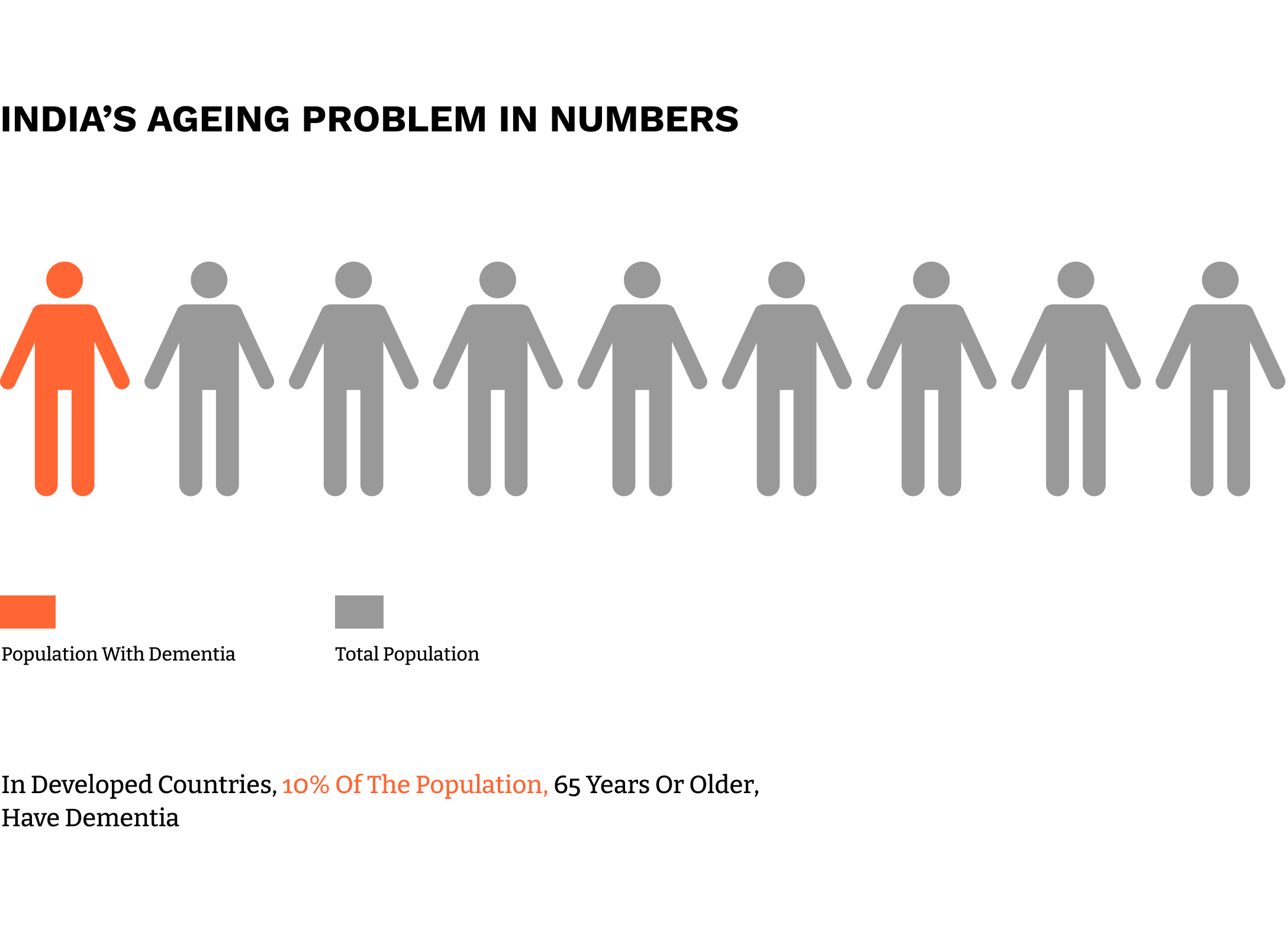

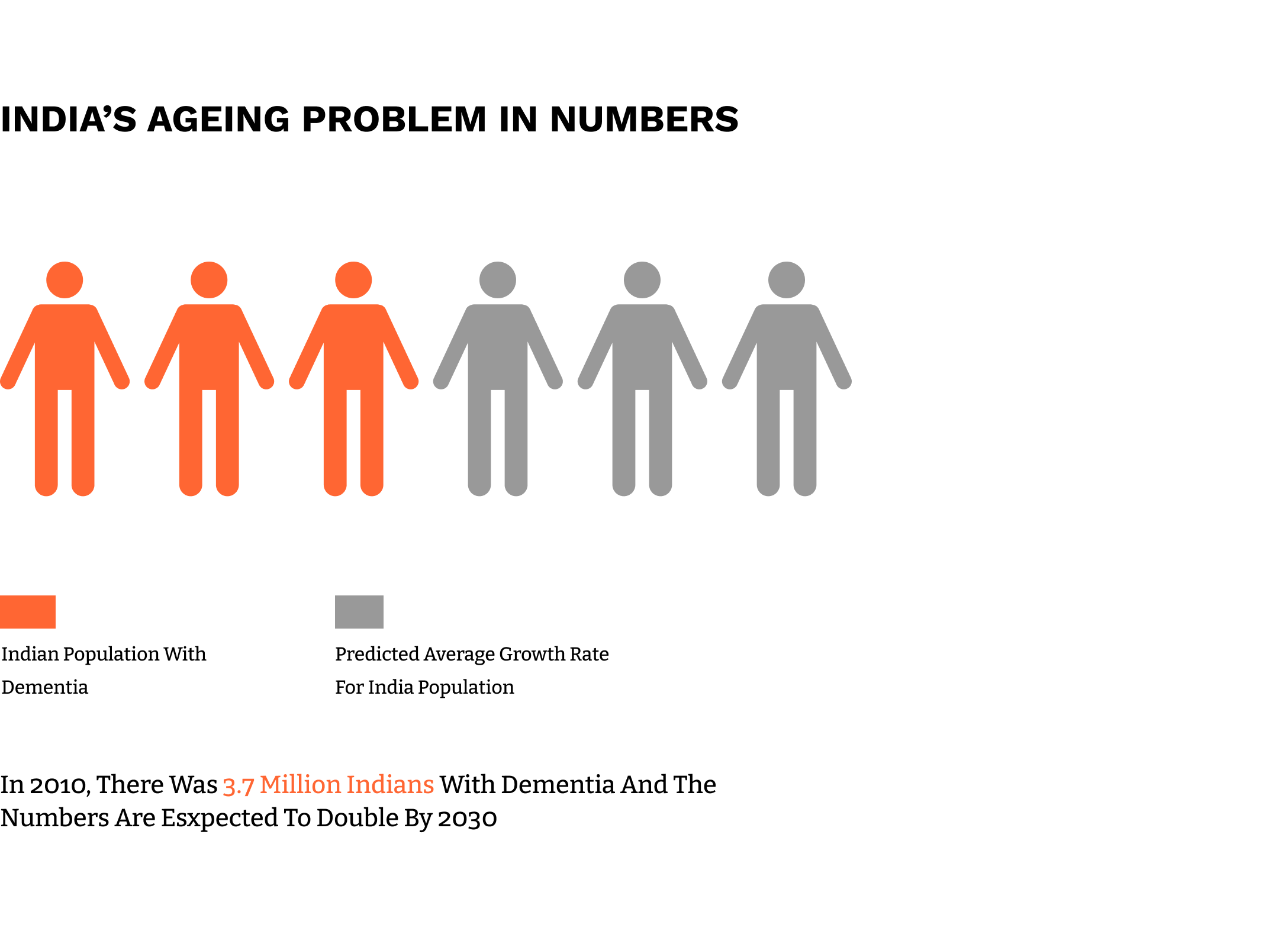

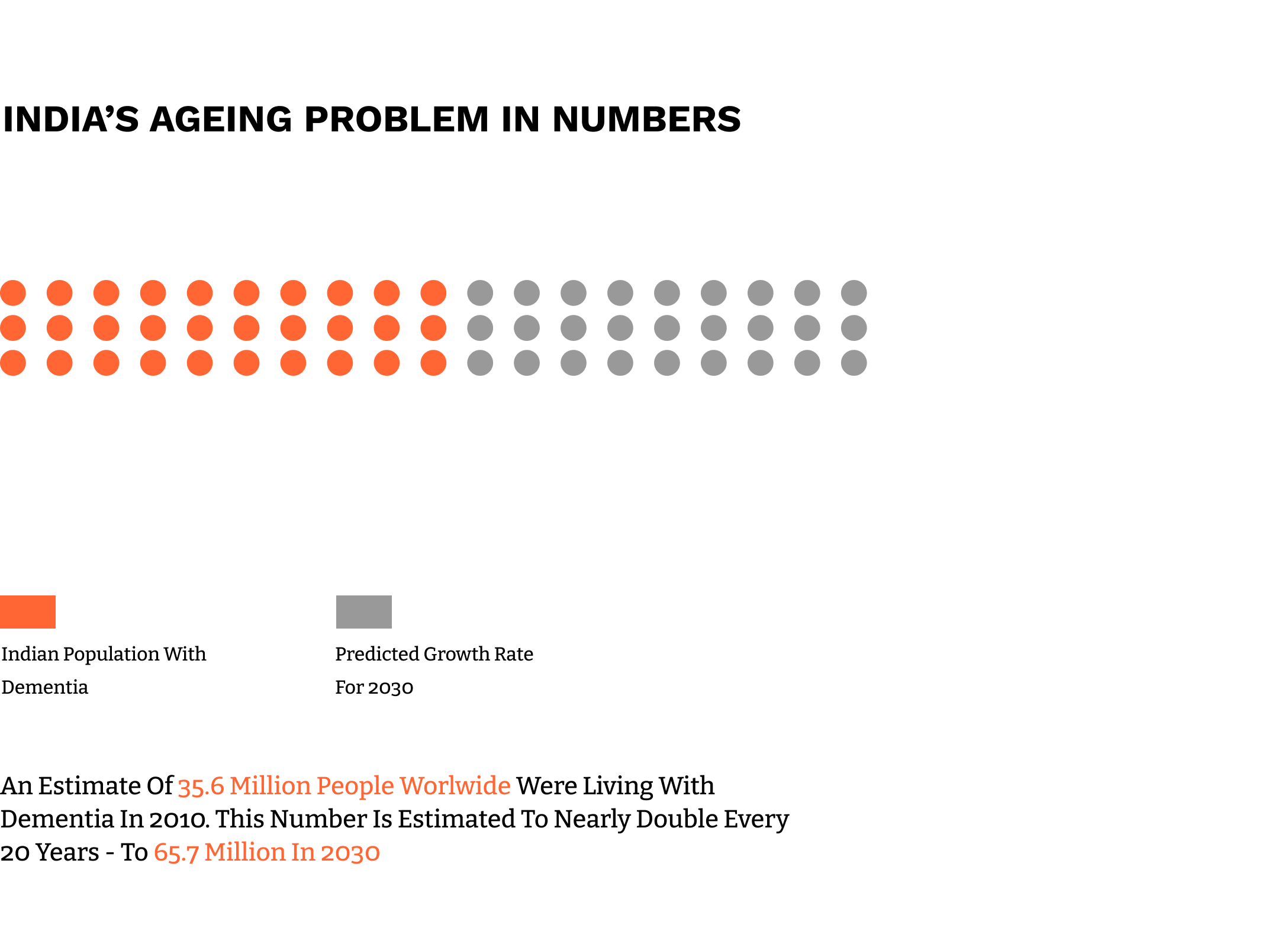

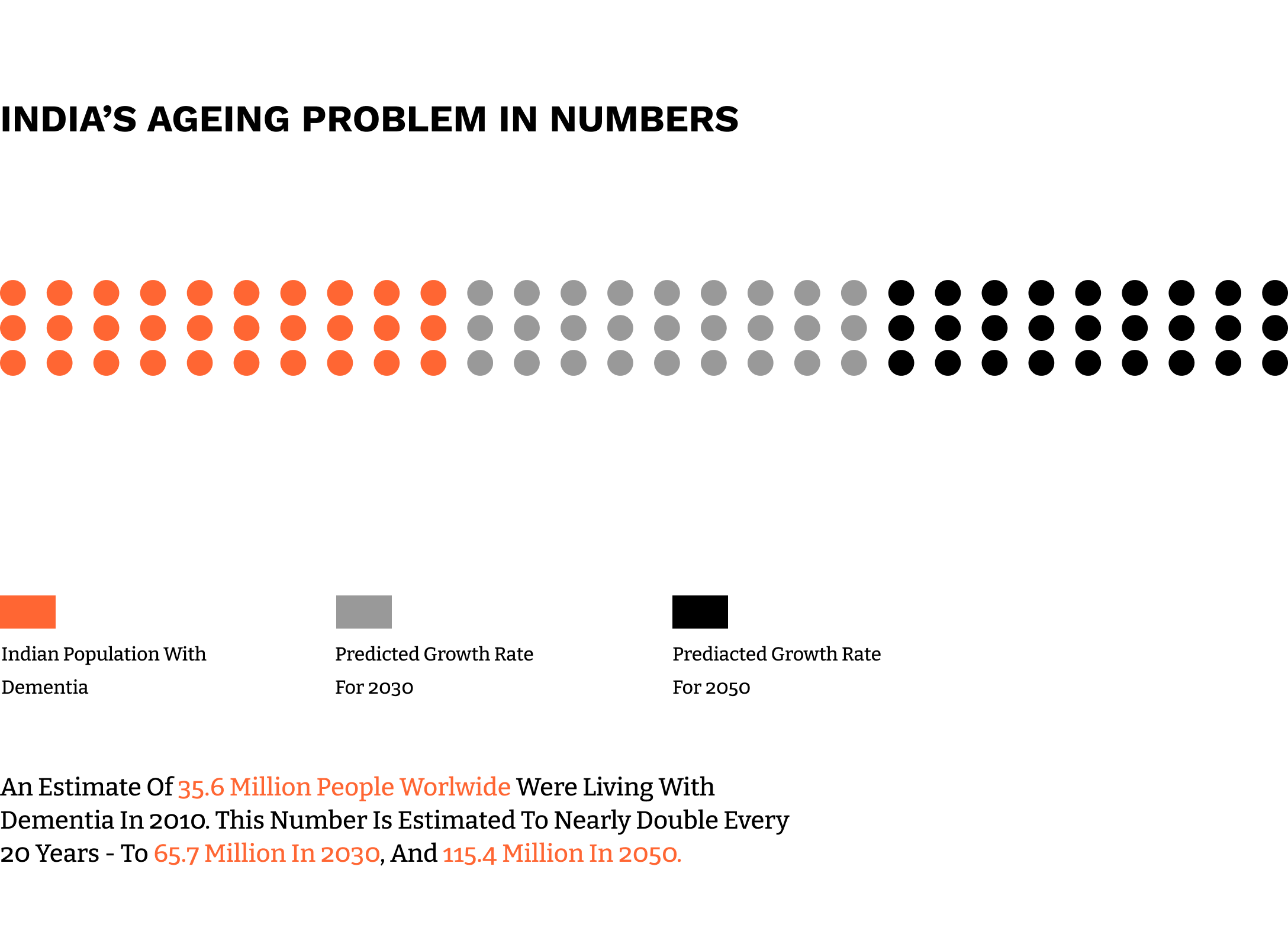

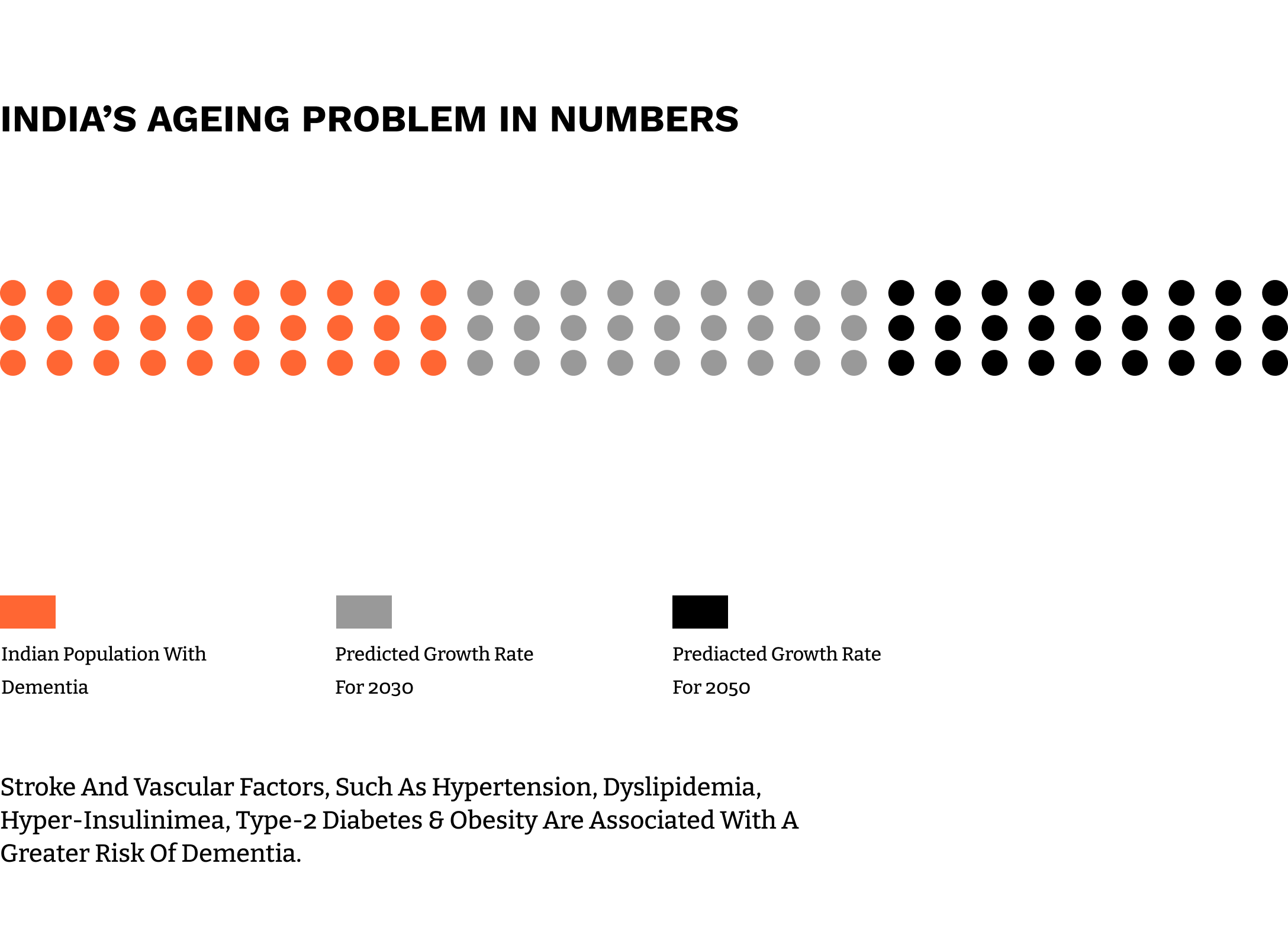

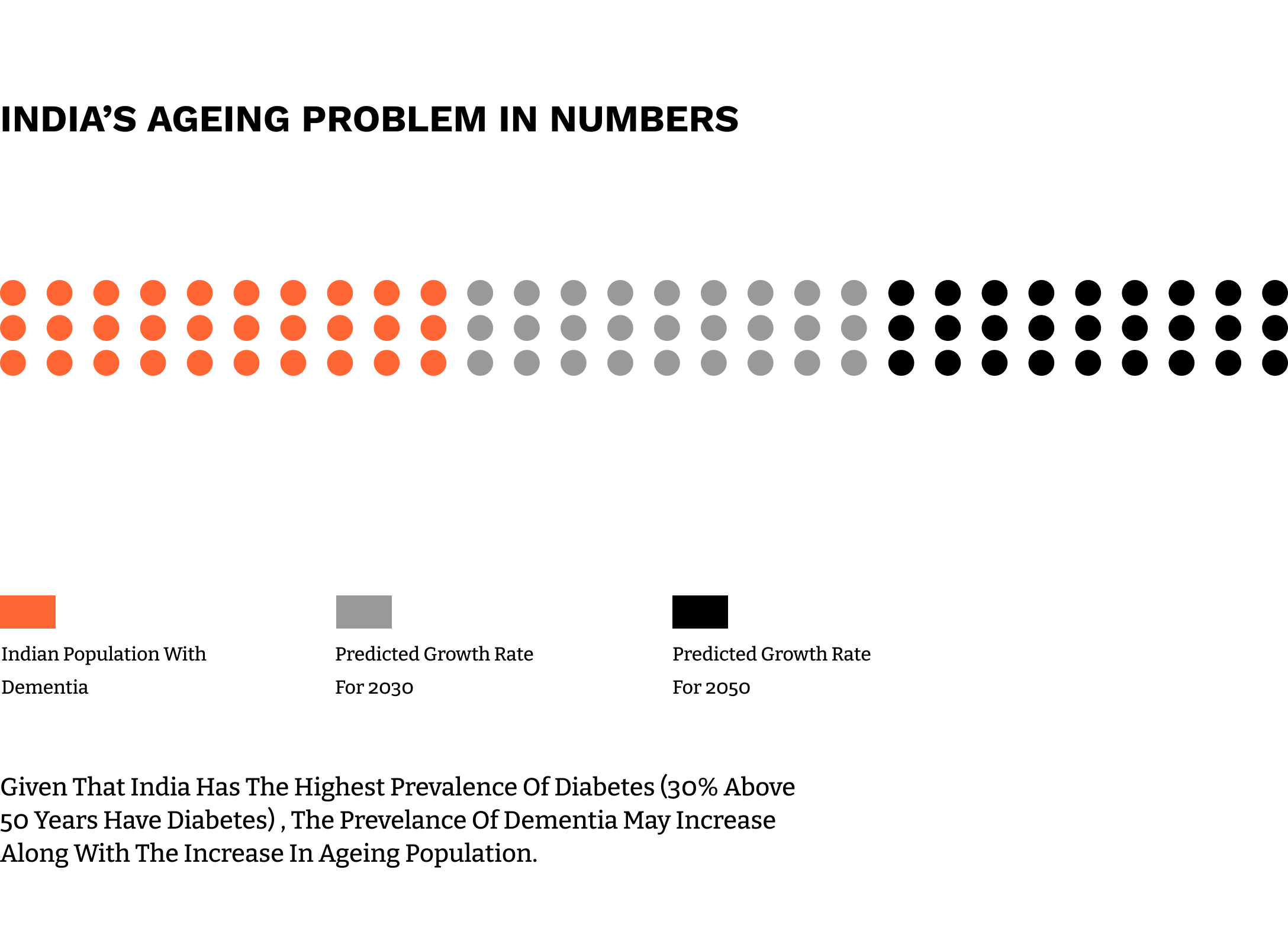

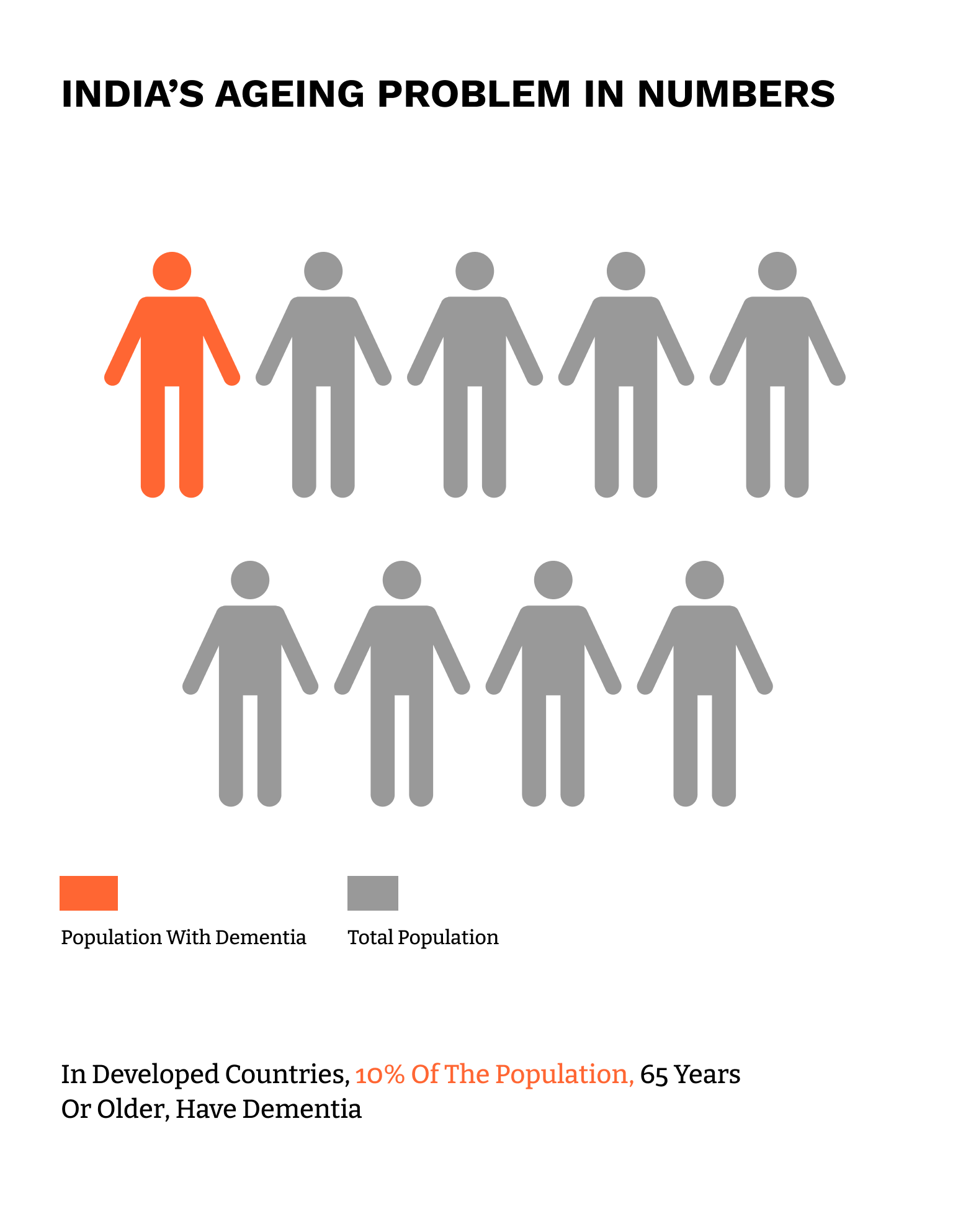

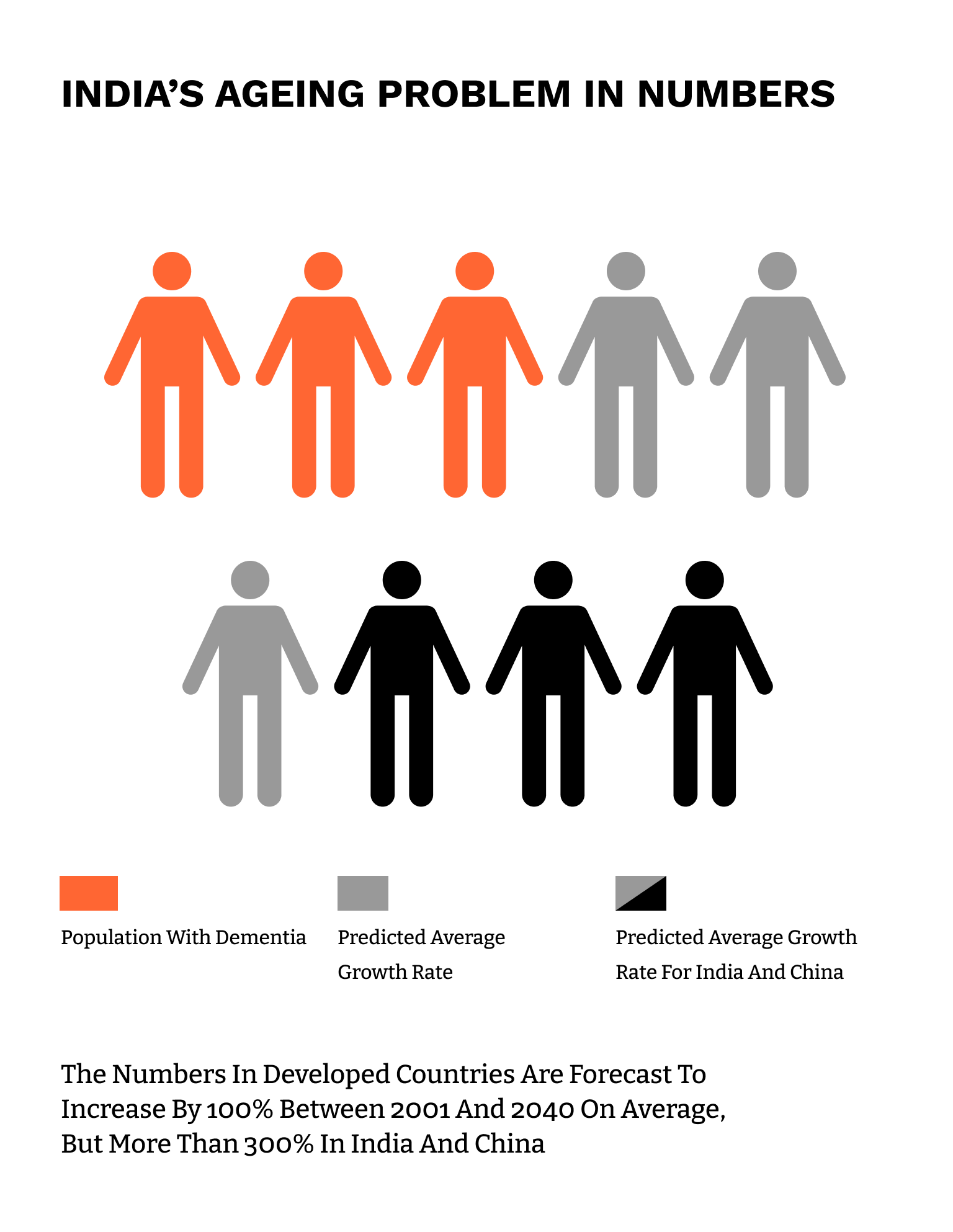

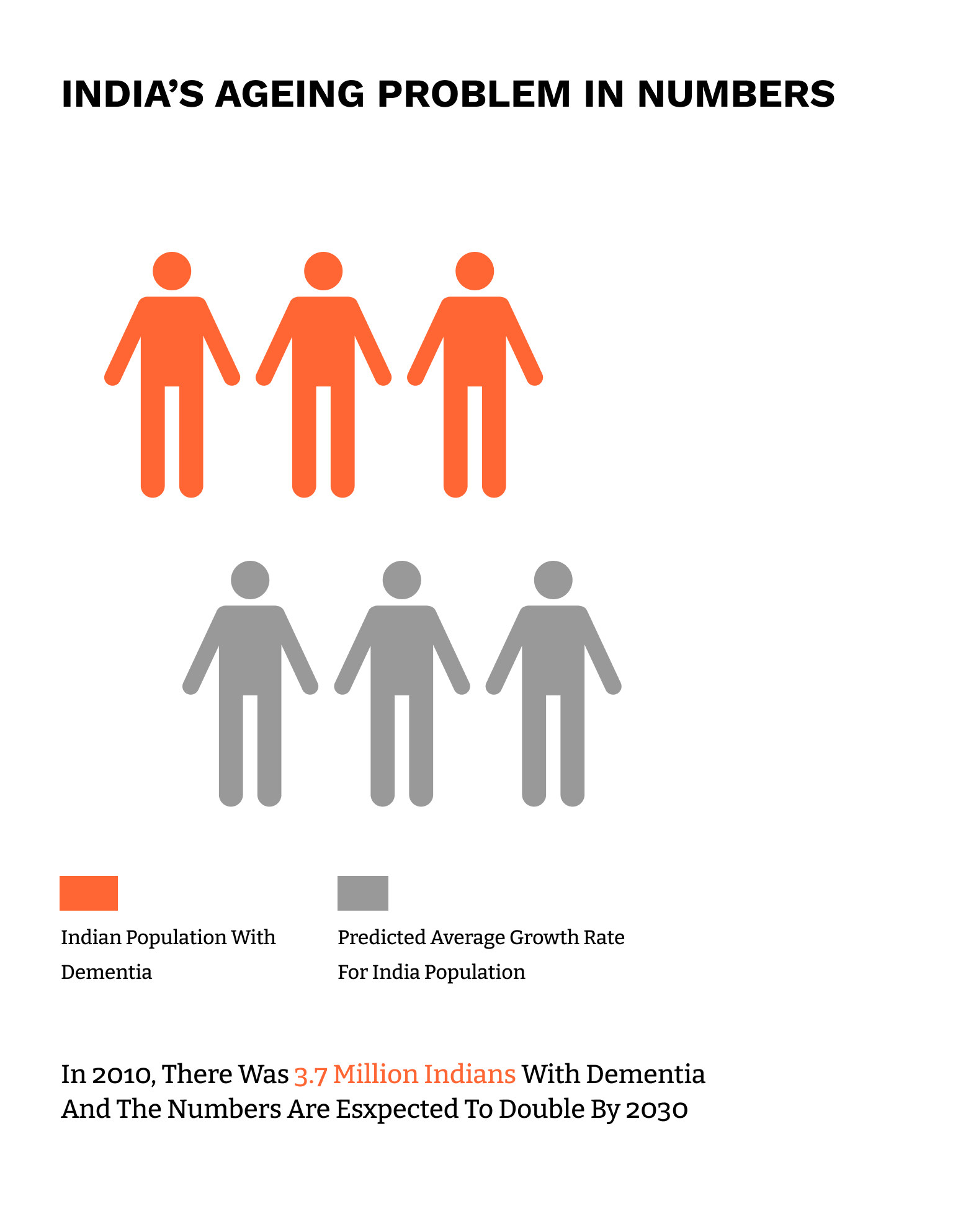

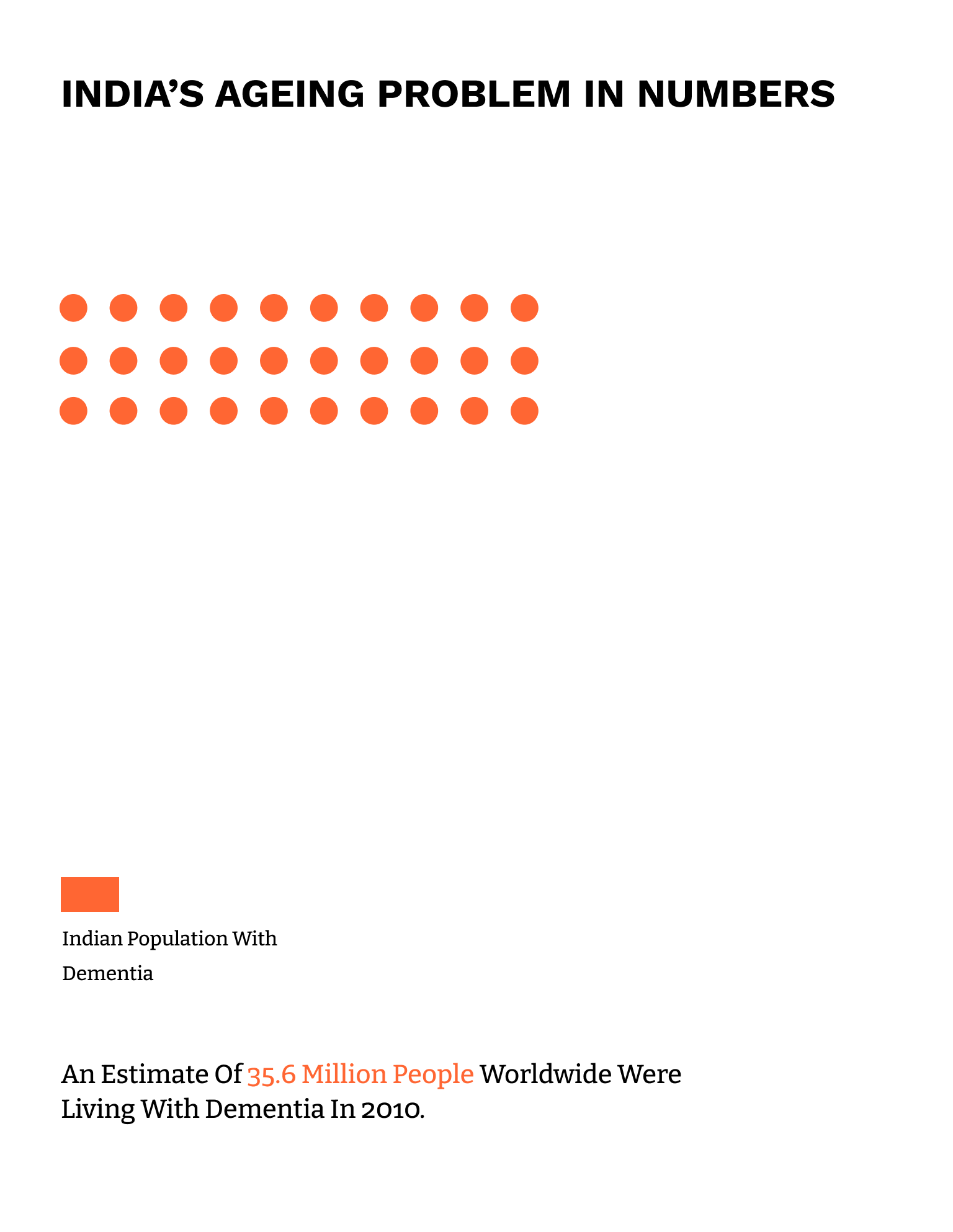

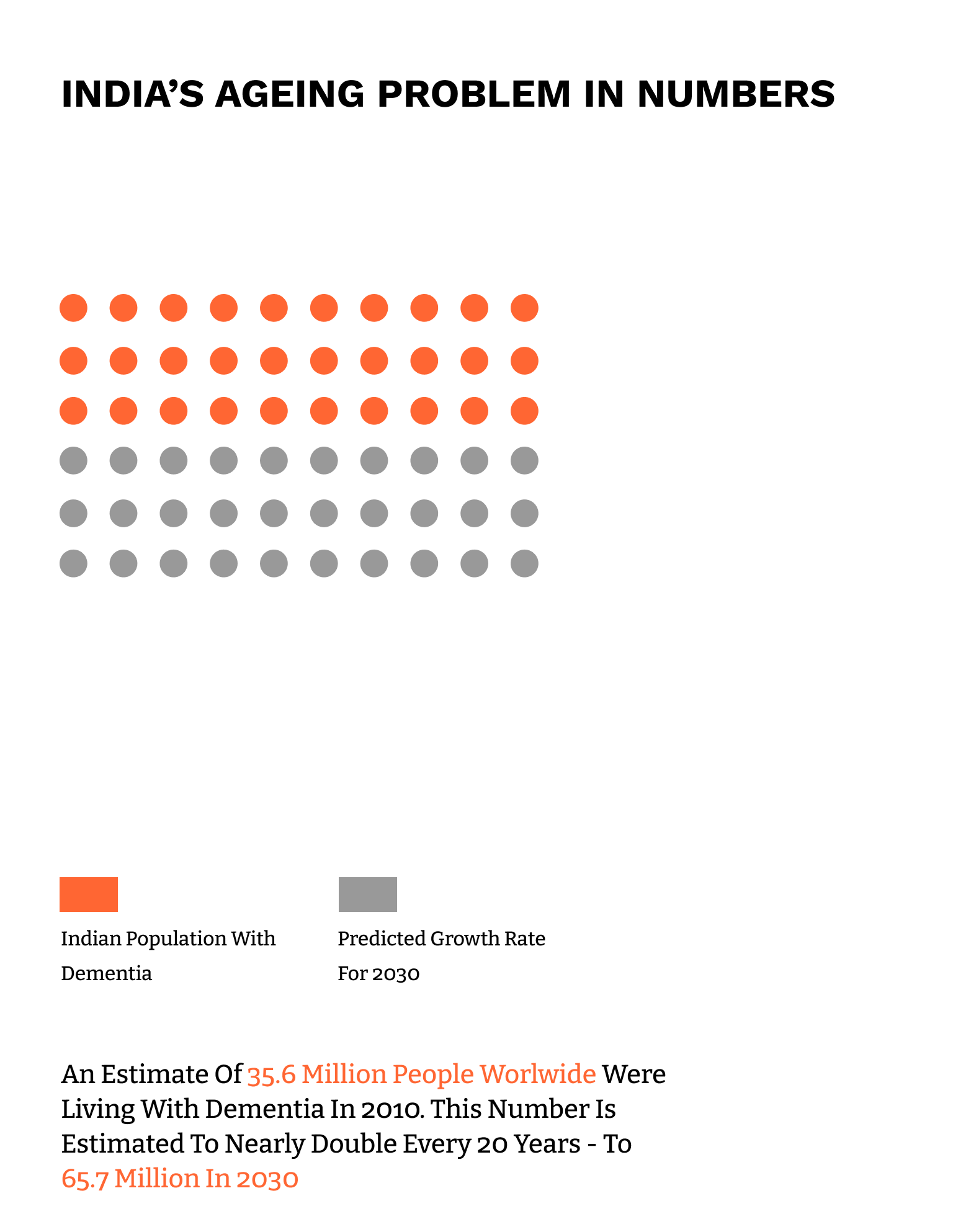

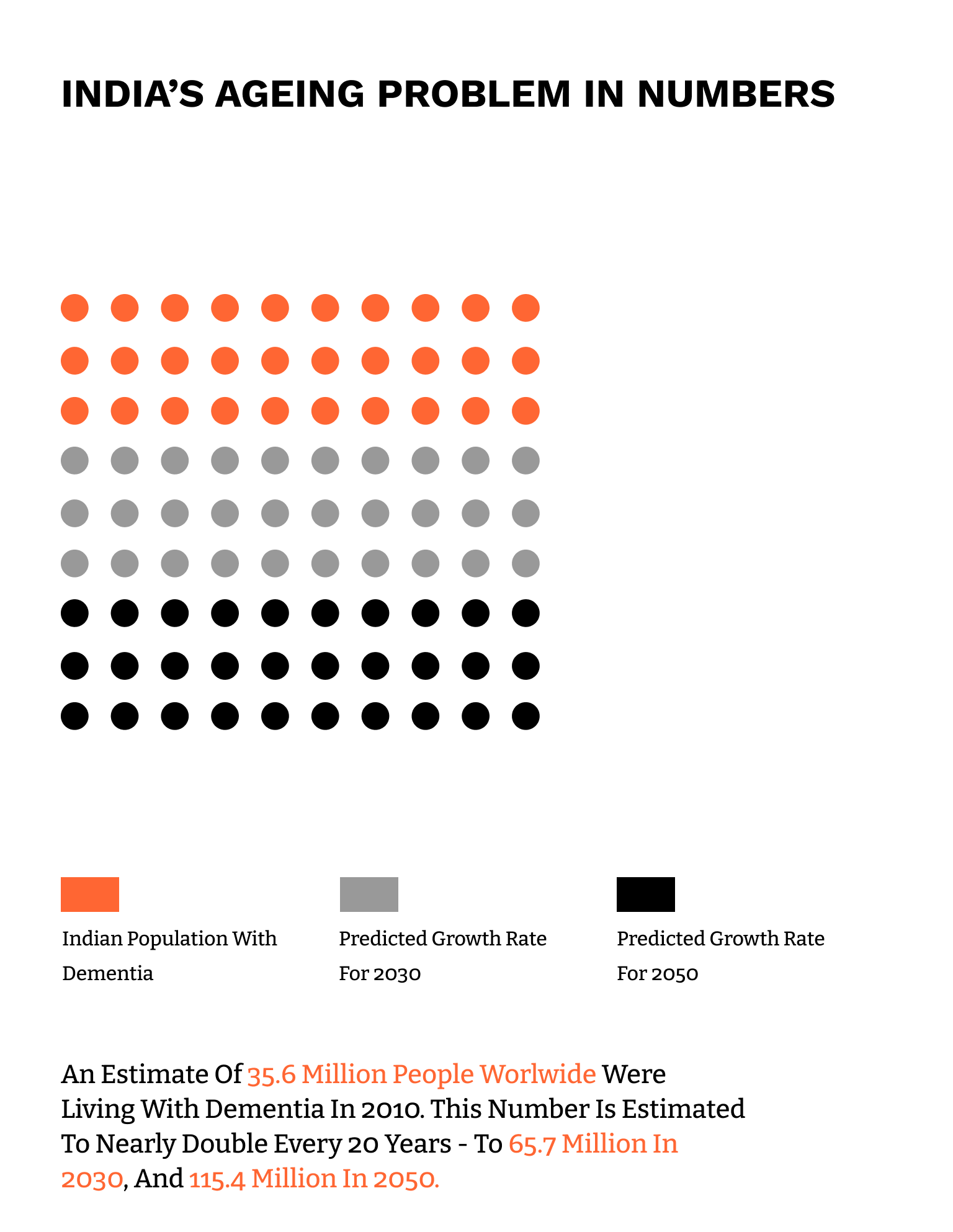

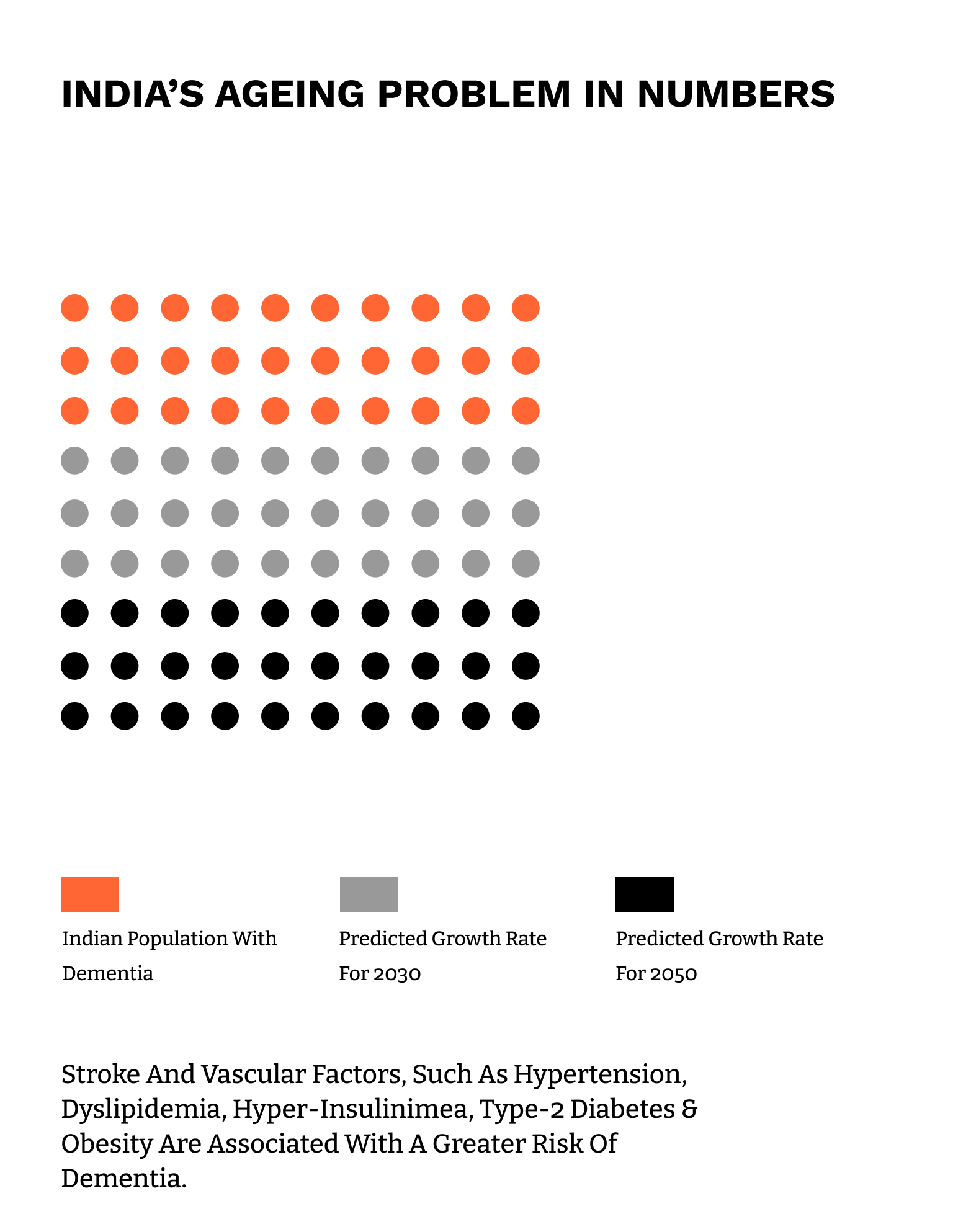

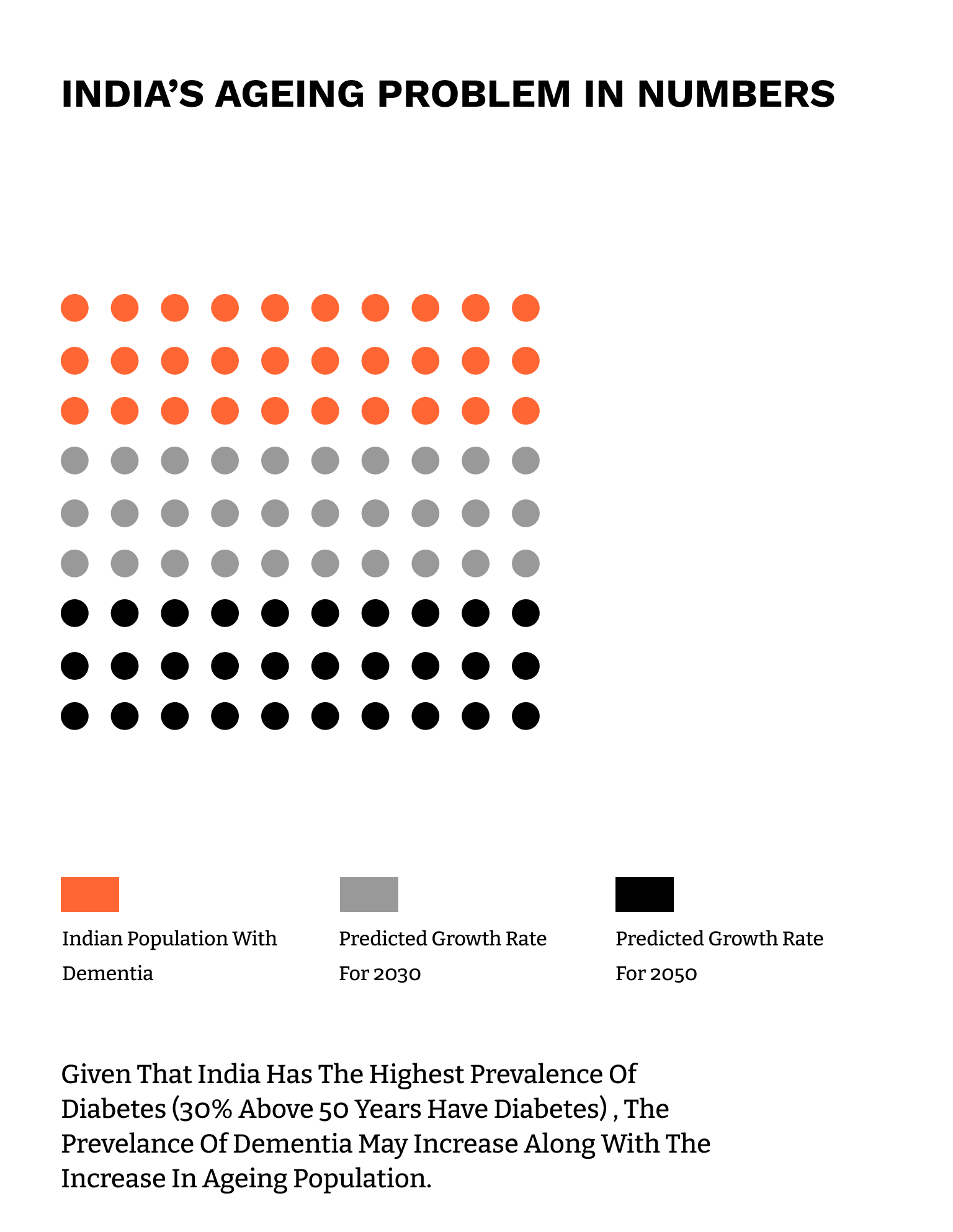

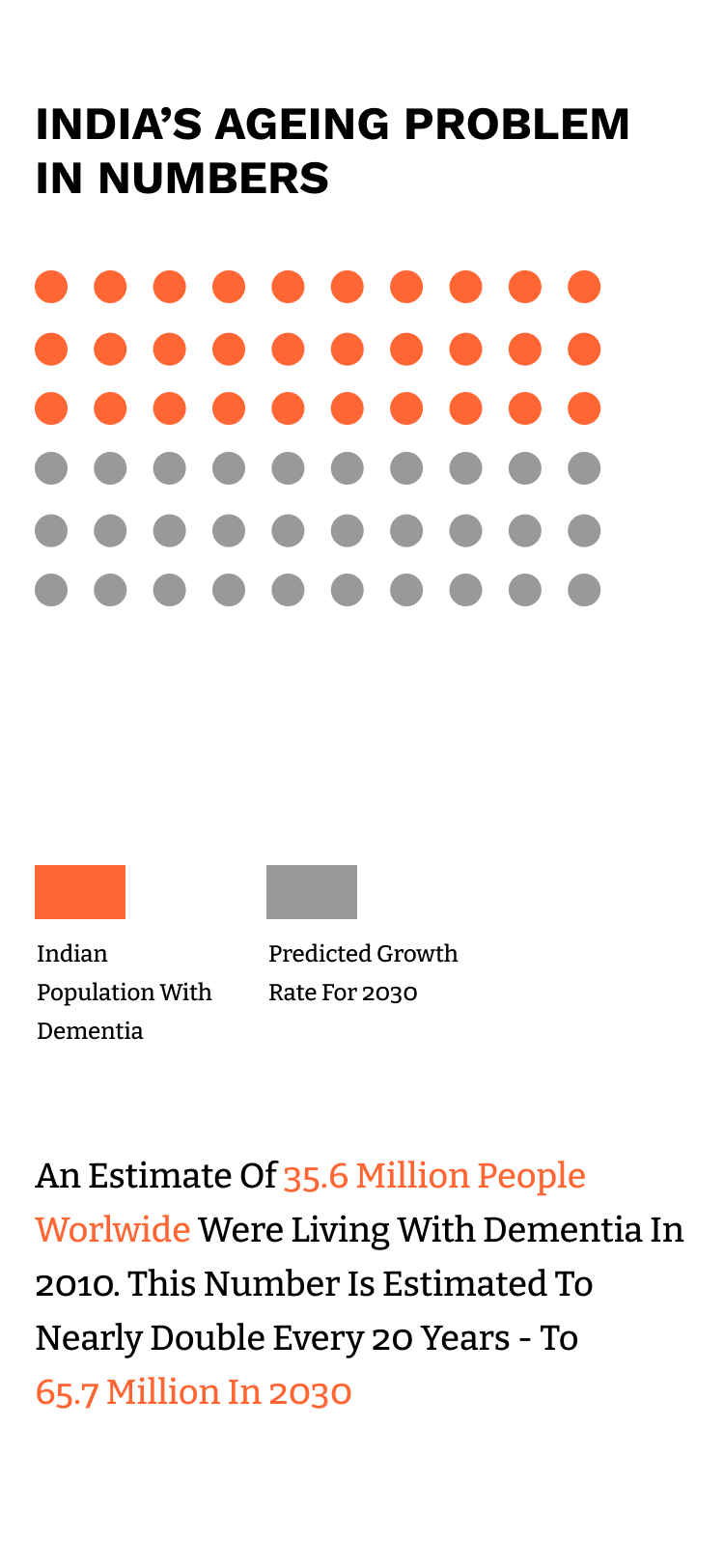

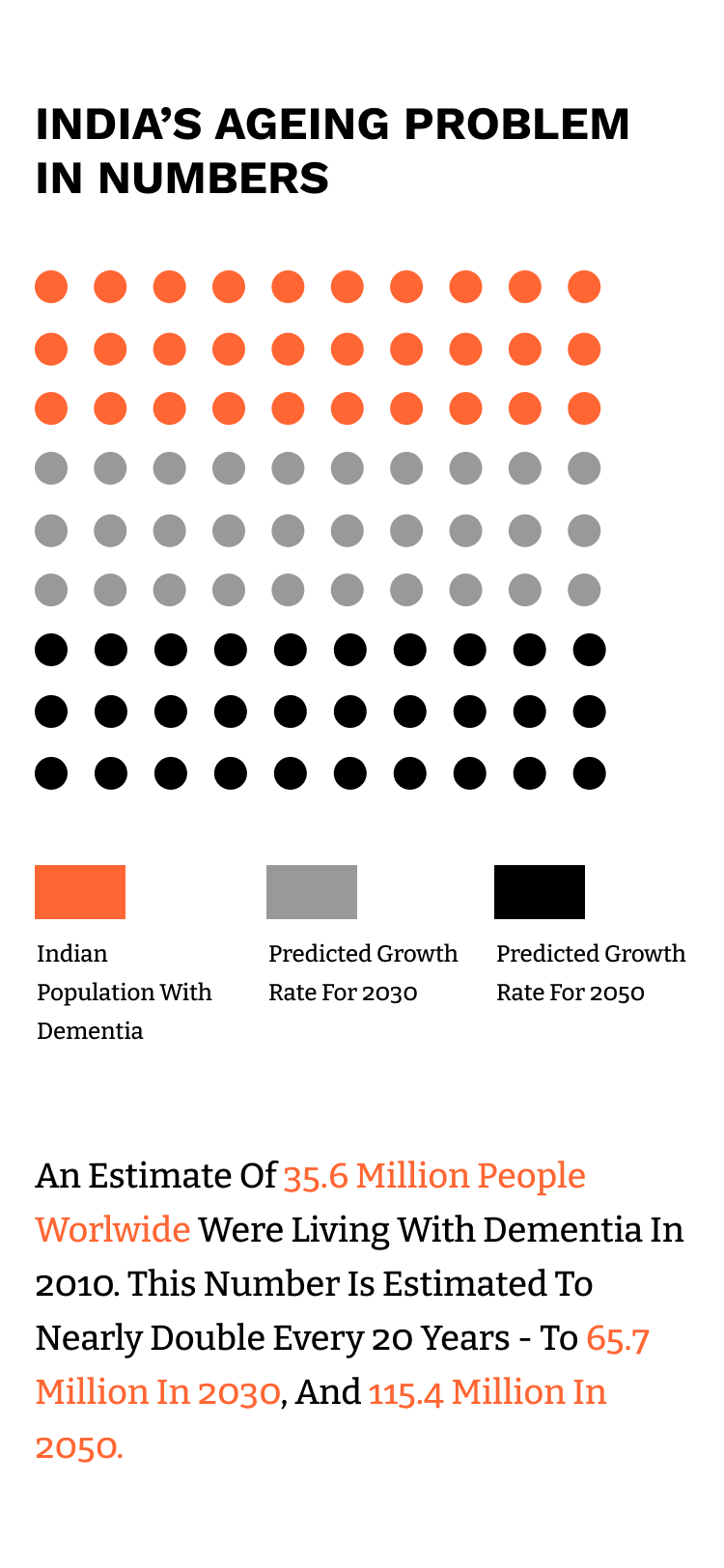

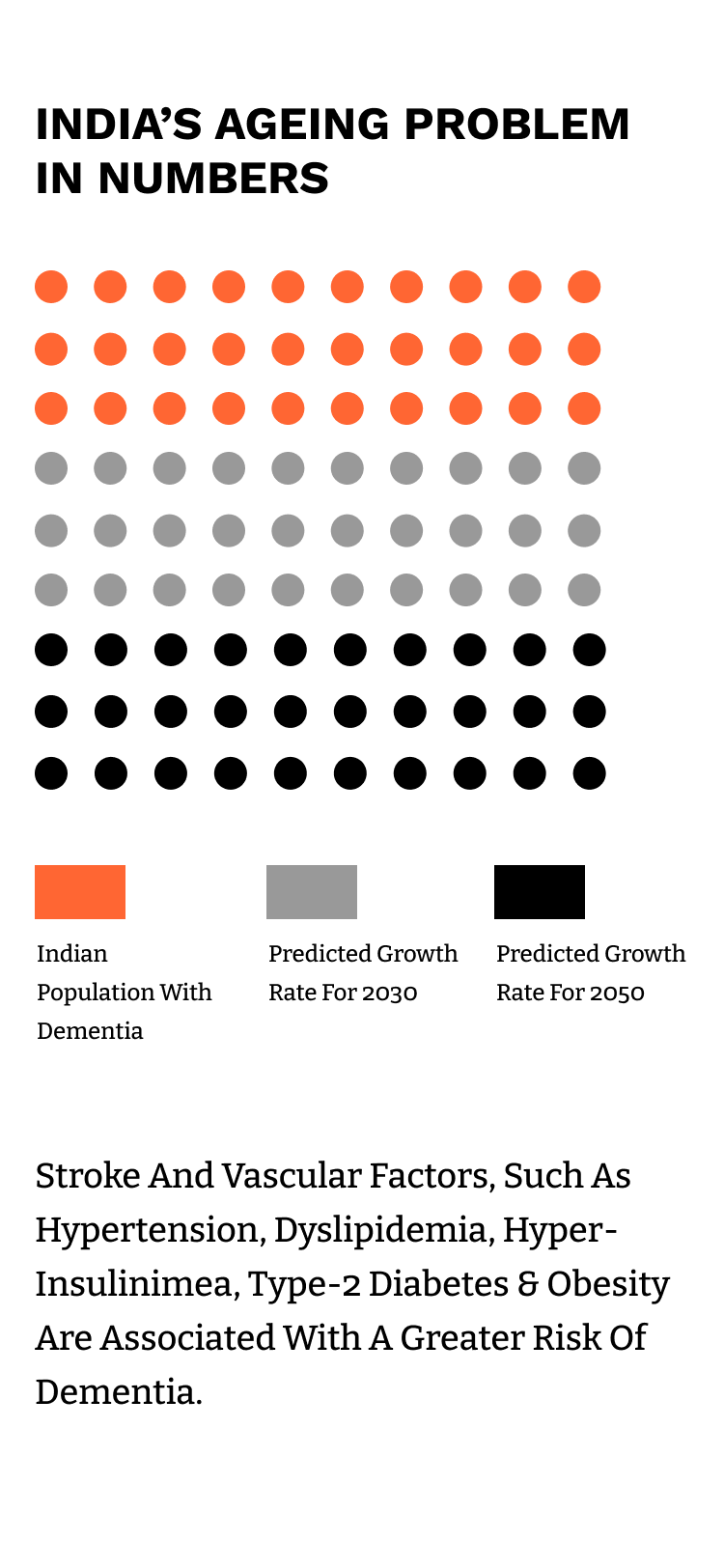

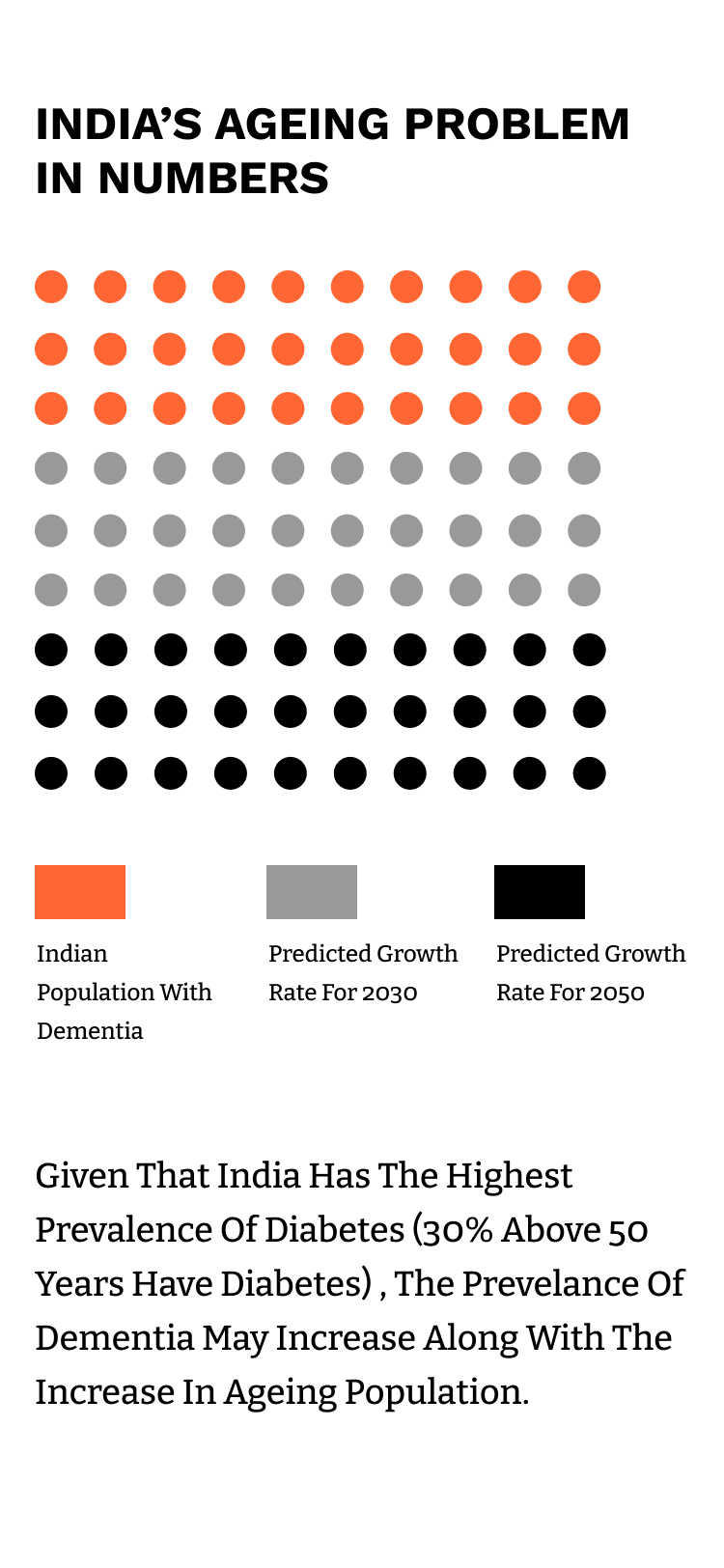

In developed countries, CBR continues, 10% of the over-65 years population has dementia. “The prevalence doubles every five years after the age of 60 and reaches nearly 50% after the age of 85 years. An estimated 35.6 million people worldwide were living with dementia in 2010… The numbers in developed countries are forecast to increase by 100% between 2001 and 2040 on average, but by more than 300% in India, China, and their south Asian and western Pacific neighbours.” Worse, risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, smoking, and alcohol abuse in India doesn’t help and “results in cerebrovascular disease-vascular dementia,” CBR adds.

The Srinivasapura playbook has previous successes to build on. The Framingham Heart Study, which started in 1948 in Framingham, Massachusetts, has helped establish correlations between cigarette smoking and increased risk heart diseases, among several research milestones over seven decades. Others, such as the Religious Orders Study, which included around 1,000 nuns and priests, also involved the cohort voluntarily donating their brains after death. It opened a goldmine of insights because many brain-related studies cannot be conducted through MRI and other imaging scans.

David A. Bennett, the principal researcher behind the Religious Orders Study, is a CBR advisor. Now the director of Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Centre in Chicago, Dr Bennett has been guiding the team of researchers and scientists at CBR led by Vijayalakshmi Ravindranath of IISc. Vijayalakshmi, 64, used to chair the Centre for Neuroscience at IISc and was also the founder director of the National Brain Research Center at New Delhi between 2000 and 2009.

“Literally every drug for Alzheimer’s has failed in the last few years, we have no medicine. What we are now trying to do the world over is to try and understand how people age,” says Vijayalakshmi. “And we cannot extrapolate data from the western world to ours because illiteracy is a risk for dementia, for instance, which is a big factor for us.”

A benign techie

“We do not have any data at all, or any such studies done so far in India,” says Kris, as he is best known, whose riches – estimated by Forbes magazine at $1.67 billion in 2015 – come from being a co-founder and CEO of software services company Infosys in a previous avatar.

For him, the age-mental health correlation in India is critical. “Are there differences in the way these disorders strike Indians? Now, India is the capital of diabetes and hypertension, and we expect that this will have an impact on ageing and people will have a lot more ageing related disorders in the country,” he says.

India, already handicapped with an anaemic health budget, is ill-equipped to handle the ballooning of its elderly and the mental health issues that accompany it. “So understanding the process… what are the causes? Are Indians going to be affected differently? Or because we are multi-lingual, a lot of vegetarian people, meditation and yoga, are there positives that could offset the negatives,” asks Kris.

The premise and promise of the Srinivasapura Ageing Senescence and Cognition (SANSCOG) project are that it could potentially help develop drugs more suited for Indian conditions and genetic construct eventually. Drugs developed in the Western world and sold in India are pricey and may not be effective on the Indian gene.

“Early diagnosis and potential treatment opportunities (can) lead to new drug discovery and development,” says Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw, chairman of biotech company Biocon. “It can also help to understand genetic differences, if any, between the ageing process in different populations based on ethnicity.” The project, she believes, puts India on par with global efforts elsewhere to find “new drugs to address unmet needs in Alzheimer’s, Dementia, Parkinson’s etc.”

CBR’s Vijaylakshmi says she got pulled into the project when Kris walked into the then IISc director Padmanabhan Balaram’s office in October 2014. He wanted to “do something in neuroscience, particularly ageing”.

She had already raised funding to start brain-related research at IISc with Ratan Tata, an early donor, writing out a cheque for Rs 75 crore in 2014. And then, Kris ponied up Rs 225 crore right after that with just one ask: set up a dedicated brain research centre on the sylvan IISc campus.

India’s demographic timebomb

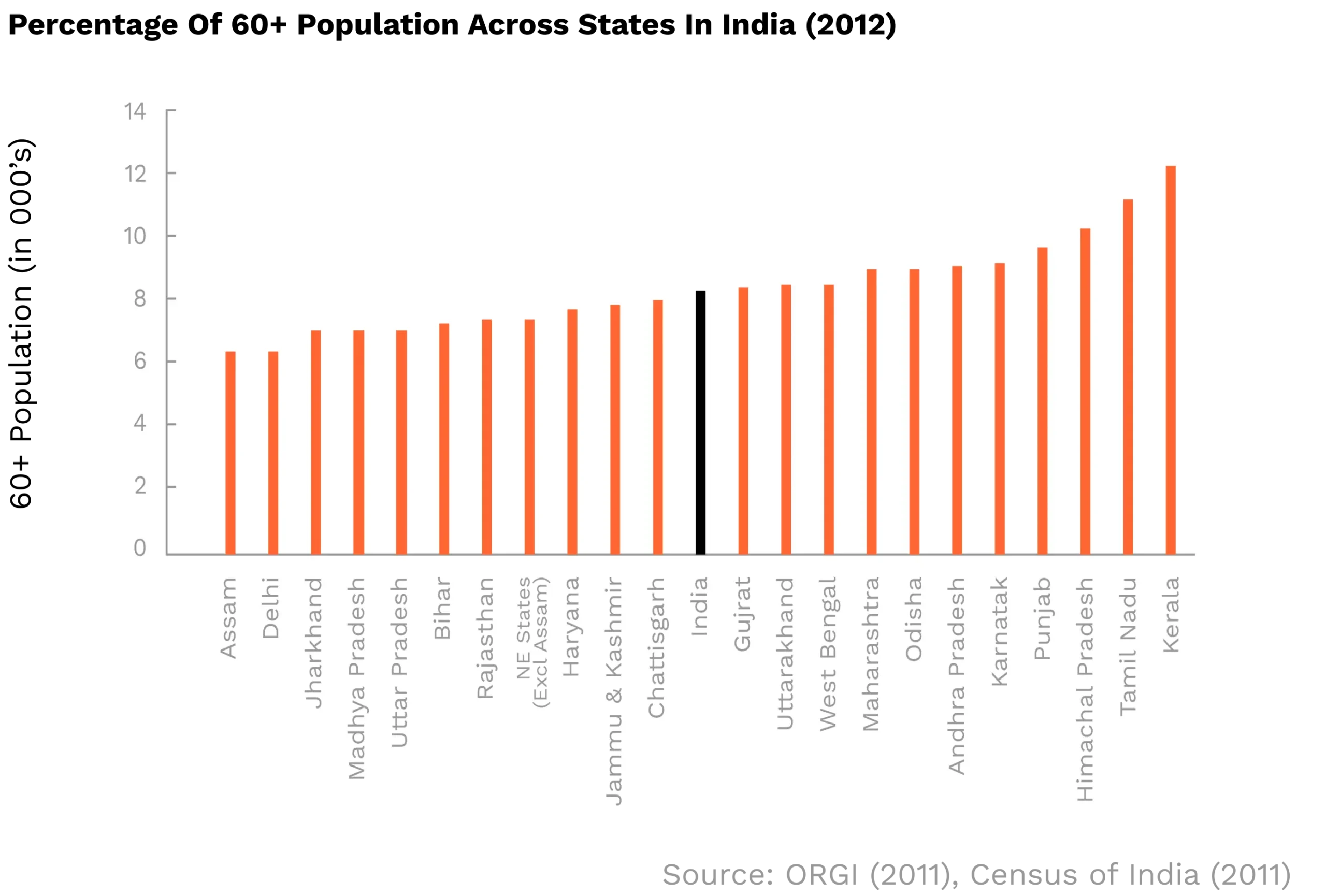

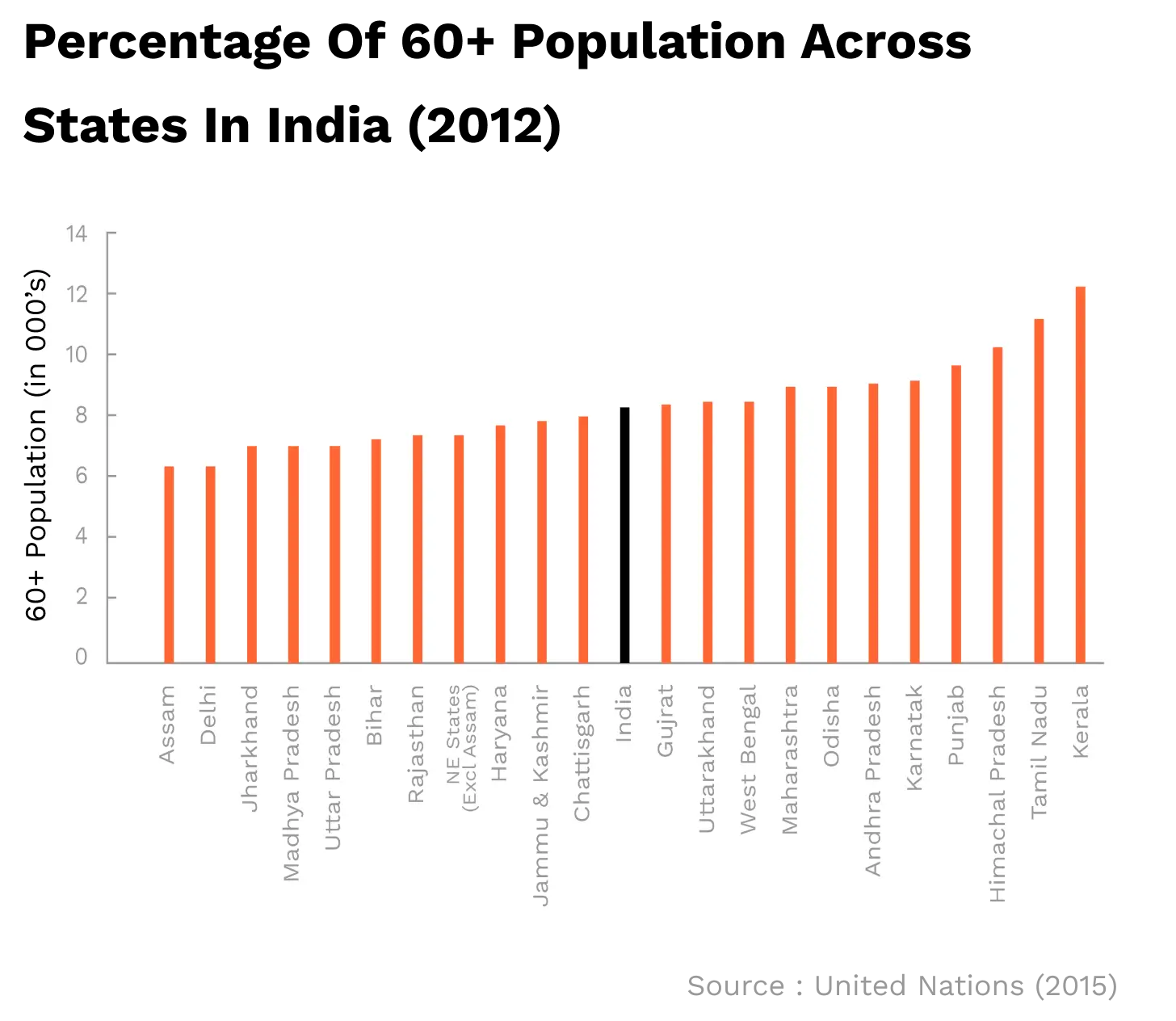

India has 2.4% of the world’s land mass and more than 17% of its population. By the year 2020, the country will account for some 14.2% of the world’s 60+ years old population. And by the end of this century, the elderly will constitute more than one-third of the Indian population, up from 8% in 2015 and 19% in 2050.

In other words, India’s demographic dividend – 40% of its population under 18 – is set to become a healthcare burden over as less as a few decades. The country’s elderly population will cross 300 million by 2050, trebling from 104 million in 2011, says a United Nations Population Fund report published earlier this year. According to research by the RAND Center for Ageing, by 2030, 45.4% of the Indian health burden is projected to be borne by older adults, who will have high levels of noncommunicable diseases.

The only way out is to come up with strategies based on insights gathered from big data. “Health policy and interventions informed by appropriate data will be needed to avert this burden,” the RAND Center said. To be sure, the projection was made in 2008 but the conclusions are not directionally wrong.

For its part, China – whose health burden on older adults is pegged at 65.6% by 2030 by the RAND Center – started a multi-decade study of its ageing population in 2011 with The China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study or CHARLS. The study, which kicked off with two pilot studies in 2008, covers around 10,000 households and nearly 17,500 individuals above the age of 45 spread over 450 villages.

“We are spending 0.8% of the GDP on research. Out of that 0.6% comes from the government and 0.2% from the private sector. Korea spends 4%, China spends 2.5-3%. I feel India needs to go to 2-3%, but the private sector has to increase significantly more,” says Kris. “The bigger picture is that in the long term if India has to be competitive, we have to have our own world-class research infrastructure.”

Back to school

The classroom in Dalasanur’s primary school has filled up with around 50 elderly people, mostly women. Men are in the fields because it’s harvesting season, a SANSCOG volunteer says.

Click here for a visual story on the Kolar project by Rajesh Subramanian.

Anu K N, a Ph.D. scholar from NIMHANS and one of over a dozen volunteers working for the program, is nervously working the room trying to make eye contact with the elderly in the room.

“I always loved elderly people, and that’s why I applied for this program,” she says while setting up her Dell laptop to work with the projector, which will beam a powerpoint presentation on the blackboard behind.

This session with the ageing villagers is the first in a series of awareness camps to be organised in Srinivasapura. The Dalasanur, Thernahalli and Chaldignahalli villages will go first. Another 20 villages will follow or will be approached in parallel to ensure that the 10,000 members of the cohort are recruited over next few months.

“How are you all,” Anu, who hails from Kottayam in Kerala and speaks Malayalam as her first language, asks the audience in Kannada. “My Kannada is not too proficient, so please bear with me.”

Over the next hour, she explains the programme, talks about its partners and probes the elderly about their mental and physical health.

Halfway, just when some of the elderly in the room show signs of their attention waning, Anu plays a Kannada movie that has an old man suffering from dementia as its central character. In one of the scenes, the old man’s son is angry and blames his father for embarrassment after an incident at a department store. The father, suffering from dementia, forgets to get a product billed while walking out. The sensors start beeping, making enough noise for everyone to notice, leaving the son red-faced.

Seethamma, Rama Reddy and others in the room have expressions ranging from empathetic to crestfallen. Many of them can now identify their ageing disorders, mostly related to memory loss.

The seasoning is done

The first cohort is now ready for the next steps, at least in terms of initial willingness required for their participation.

Then, there’s also a cash reward of around Rs 1,000 for each completed cycle of tests and data capture — a big deal in a district where the per capita income of around Rs 94,000 lags the average Rs 1.26 lakh elsewhere in Karnataka.

And above all, the cohort members will get expensive, sophisticated medical tests done at no cost.

“Will you folks also treat us,” one among the elderly asks.

“No. We will share each test findings and perhaps even advise you where to seek treatment from. We will not be offering any treatment. Is that clear?” Anu responds.

“If we don’t set the expectations right at the beginning, it might affect the program,” she tells FactorDaily.

After the session gets over, volunteers Shivanand, Shivakumar, and Harikrishna, go around with basic registration forms, asking for the names, contact details. Above all, they are also taking consent from the elderly to contact them later in the programme.

The next step involves fixing an appointment with the elderly for a visit to the local health centre in Srinivasapura or the SANSCOG site office where over 30 medical tests including blood samples to cognitive assessments will be done. After that, some of them will be given Fitbit health bands and blood pressure measuring devices to be worn 24 hours – even at nights when there’s no physical activity in sleep. Several other parameters are also tracked.

Around 1,000 of the total 10,000 people in the cohort will be brought to Bengaluru over the next year for MRI scanning.After crossing the first barrier of creating awareness, educating and recruiting the cohort, the core part of the project will begin: that of collecting data, storing them and finally start sifting through them for finding answers.

Big, deep data

All the medical data captured from 10,000 people will be first stored in a yet-to-be-named Android app developed by the CBR team at IISc. The data collected by field agents and volunteers over the year will be channeled to a central supercomputing server at IISc.

And this is where the data sets will start getting bigger, and more complex. For instance, each individual’s data could go up to few Terabytes in size. Genetic data alone can be as big as 2 Terabytes per person. MRI data can go up to 200 Gigabytes depending how much of processing is done.

The site office in Srinivasapura is where data is first harvested. “They first give their blood, which goes to blood biochemistry evaluation, then DNA from which we do whole genome sequencing. Then they undergo all other tests including height, weight, body mass, ECG, blood pressure, we do carotid doppler test, hearing ability, eye scan, and so on,” says Ganesh Chauhan, a CBR scientist. “And then we have a lot of socio-economic data. The genetic and MRI data form the bulk.”

There are more than 30 medical examinations in all.

“We also give them words to remember and test memory. We give them an image and ask them to draw it. [There are] verbal screening, go-no-go test to check reflexes and cognitive abilities,” Chauhan adds.

All data capture will be done through a software application developed in-house, right from the time volunteers visit homes for initial registrations to complex medical tests.

With each individual’s data running into a few Terabytes, the total storage required will be in Petabytes for sure. Currently, the server room at IISc can store data up to 400 Terabytes. It will need an upgrade very soon.

“The problem is we cannot calculate it (the exact estimate) because we have to follow them next year. Other than the genetic data, which is needed only one time, the rest have to be recaptured again, every year,” says Chauhan.

Chauhan looks up to the Framingham study for inspiration. “It’s a study that opened heart to the world, and they are now in the fourth generation of the study,” he says. In much the same way, he believes such study cohorts need to go on and on, across the next generations, for them to deliver any definitive results.

So what happens to the data lifecycle after a cohort member dies?

“Death is really not a loss of data actually because if a person had biological ending the important thing for us to understand is what led to the death. That would be much more insightful and will add to the data. If you know the cause of the death and what happened leading to it, did he or she die of a stroke, vascular risk factor and so on,” says Chauhan.“For all people, we want the end point data,” he adds.

the number cruncher

After on-the-ground volunteers have collected data, done the medical tests, and documented datasets for every individual, Kahali, the Michigan State University Ph.D., at IISc’s CBR lab gets into action.

By sifting through Petabytes of datasets over the next few years, Kahali aims to build models and develop software algorithms, which will help predict the onset of brain-related diseases early enough.

“In these kind of studies, they are also being assessed at a higher level by neurologists who are looking for signals to detect cognitive impairments. The hardest part is getting a neurologist,” says Kahali.

Her software predictors could replace the need for a neurologist in conducting cognitive assessments.

“What if i can develop some predictors that will not take so much time? If we’re interested in daily labourers in a particular village, what if they get tested and we predict (using algorithms) what could have been predicted by a neurologist.”

For Kahali, ensuring that every single piece of data is captured and shared back with her at IISc is crucial to find answers to the dementia problem.

“One thing is that you face a challenge about is the detailed look that people like us having trained are always looking for. And it’s very hard to make others on the ground, understand that. So they are like, ‘One cell of data is missing, so what?’” she says.

A public health expert says the accuracy of data capture on a project of this scale will be crucial. “Previously, people have been looking at a smaller set of population and within a narrow set of variables. A broad range of data capturing like this hasn’t happened before yet in India,” says Srinath Reddy, president of the Public Health Foundation of India (PHFI), a health policy NGO.

The more data sets, the more robust the model, Kahali says. “Let’s say I am dealing with only a few individuals’ data. The biggest challenge lies in the fact that I have so few actual demented individuals, whatever model I do, no matter how many simulations I do, my simulations are getting biased,” she says. “I am trying to get hold of better and larger data sets.” Kahali is a physicist who later studied computational biology.

Genome india

While incubating the research project at IISc, Kris and others realised the need to build in parallel an Indian genome database because nothing of that sort currently exists.“While doing this and while looking at genomics data, we said why don’t we also kick off a genomics project in India because we don’t have a gene pool of Indians

anywhere in the world,” Kris says.So, Genome India was born — its mission to gather genetic information and to catalog the amount of genetic variation among Indians.

It’s better late than never. For instance, while India accounts for more than one-sixth of the world’s population, the DNA sequences of its people contribute a meagre 0.2% of the global genetic databases, according to the BBC.

Already, over a dozen organisations including LV Prasad Eye Hospital in Hyderabad and Mohan’s Diabetes in Chennai have decided to contribute their genomics data to the Genome India pool.

“It will create data for research purpose. That can be used for genealogy, where did the Indians come from, why are the Indians more susceptible to diabetes, is diet causing a problem…all those things can be studied once this data is available,” says Kris.

Dr Reddy, the health policy wonk, calls the project long overdue given the unique and complex traits of Indians. “Everything from distribution of body fat, dietary habits, metabolism is different for Indians,” says Dr Reddy, who previously headed the cardiology department of the All India Institute of Medical Sciences.How does a genetic information catalog connect with a brain research project?

“First of all, there can be two or three broad perspectives: one is from disease point of view; second is our population, how did we emerge, where did we migrate from; and third is the moment we have a catalog, it is much easier to do any kind of genetic screening or counselling because then we will know the variations,” says Kahali.

She is also going to be relying on Genome India’s datasets for training the algorithms she is will be responsible for building to help predict the onset of ageing disorders early enough.

“On CBR part, we can say that we are aiming for at least 1,000 to 2,000 whole genome sequences in the short term, and around 20,000 from across different regions and diversity over 3-4 years,” Kahali says.

Conditions such as Alzheimer’s, diabetes, liver disorders, obesity and others have a particular genetic component to them. “If we carry some kind of variation, then we are more susceptible to developing that medical condition rather than others who

are not carrying that particular genetic variation,” says Kahali.

Without its own genomic database, India has been lagging.

“If we could document the entire set of genetic variations that exist in the Indian population, we will be able to associate them with different disease conditions. Eventually, that will help us in tailoring treatments towards each individual,” explains Kahali.

The big picture

For Kris, the research conducted by the six chairs he’s funded at Indian Institute of Technology, Madras and IISc, CBR, the Kolar project, and the Genome India initiative are all part of a bigger game plan. Each of them will form building blocks for understanding ageing-related disorders in India and over the next few decades, hopefully, help develop solutions to manage them better, delay the onset of dementia.

While CBR and the Genome India project will ensure there’s India specific big data available for advanced research, the six chairs – three each at IISc and IIT Madras – will run deep research projects, participate in shaping global understanding, and come up with potential solutions and products. Most importantly, the chairs will help develop a specialised pool of local talent in the areas of brain research in India.

“In my lifetime if we create a large, world class research facility, that’s a first step. Nobody has found a cure for Alzheimer’s for the past 100 years, right? I don’t want to say that we are going to find it in the next five years, but I don’t know…,” he says. “This is a long shot.”

Is there a personal reason that drives Kris so much into brain research that he’s signed out some Rs 300 crore (this includes the Rs 10-crore each research chairs)? For instance, Google co-founder Sergery Brin had donated $50 million in 2009 to find a cure for Parkinson’s after discovering that he carried a genetic mutation that sharply increased his risk of developing the neurological disease.

There’s nothing personal in this for Kris, say people who have spent time with him. His passion is brain science and possibilities research around it throws up.

Biocon’s Mazumdar-Shaw says her home city Bengaluru’s “fusion approach to Bio-IT will make this study path-breaking”. Bio-IT, as in biology-information technology. She adds: “Moreover, knowing Kris’s attention to detail, he will drive digital discipline in this study to make it as significant as the Framingham Heart Study. The fact that this study is being designed very thoughtfully to leverage digital devices at an individual level makes it that more comprehensive and more sophisticated.”

Mazumdar-Shaw has been an independent director on the Infosys board since January 2014. Kris stepped down as executive vice-chairman of the company that

October.

B N Gangadhar, the director of NIMHANS, India’s premier neurosciences education, research and medical institute, has realistic expectations with regard to outcomes and the time it will take. He believes while the first decade will deliver only optimal results, the real definitive answers will take much longer to come by.

“The richness of data will keep getting better,” says Dr Gangadhar, whose doctorate is in yoga and mental health.

PHFI’s Dr Reddy says the biggest challenge before the Srinivasapura project is to ensure that those recruited as part of the cohort stay and stay till they die. “It will affect the ongoing study otherwise. Repeat visits, year after year is going to be crucial,” he says.

At Dalasanur, for now, Seethamma and others are oblivious to the project’s grand, world changing ambitions. What’s attracting them now is a host of benefits, including the cash reward. “Free health checkup and money sounds good,” she says through a translator.

(A version of this story ran in the print edition of Mint newspaper on November 27.)