Morningstar calls it

design, build, grow.

THE MAN WHO

GROWS BRIDGES

FROM ROOTS

MAWKYRNOT

VILLAGE,

PYNURSALA,

MEGHALAYA

Morningstar calls it

design, build, grow.

In Meghalaya’s remote hills, one man is preserving a 500-year-old tradition of living root bridges—before it disappears.

by Pankaj Mishra

We had been walking for over an hour—down a steep, moss-slicked staircase cut into the hillside of Rangthylliang, a remote village in Meghalaya’s East Khasi Hills. The forest thickened with each step: bamboo groves pressed in close, trunks darkened by rain, the sound of a stream somewhere below.

And then, around a bend, it appeared.

A bridge. But not built—grown.

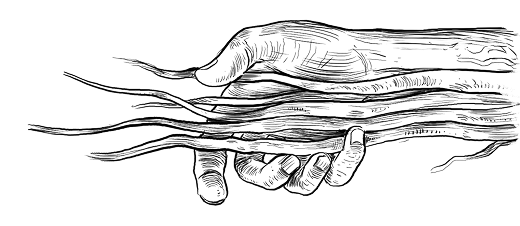

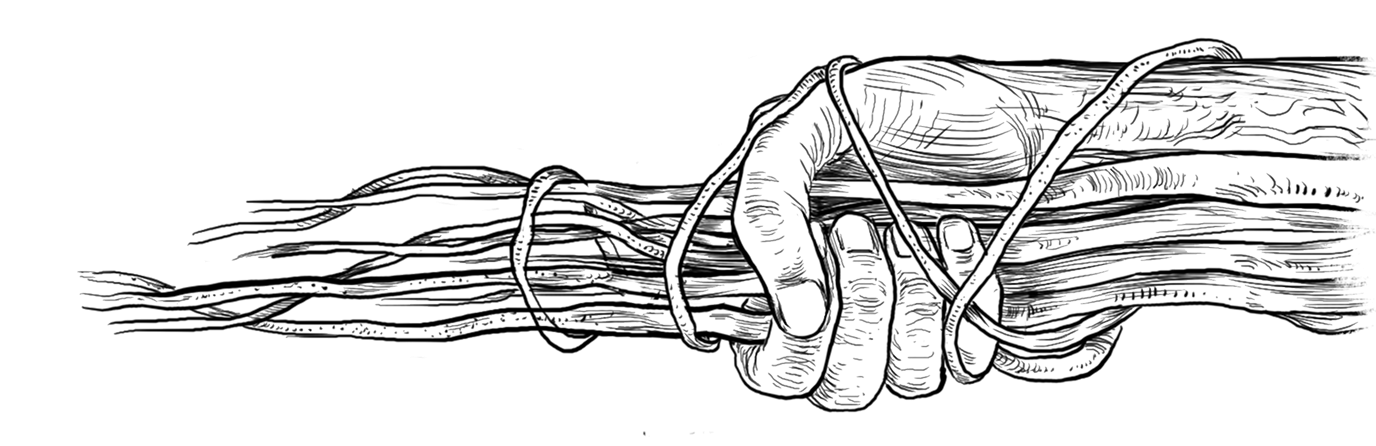

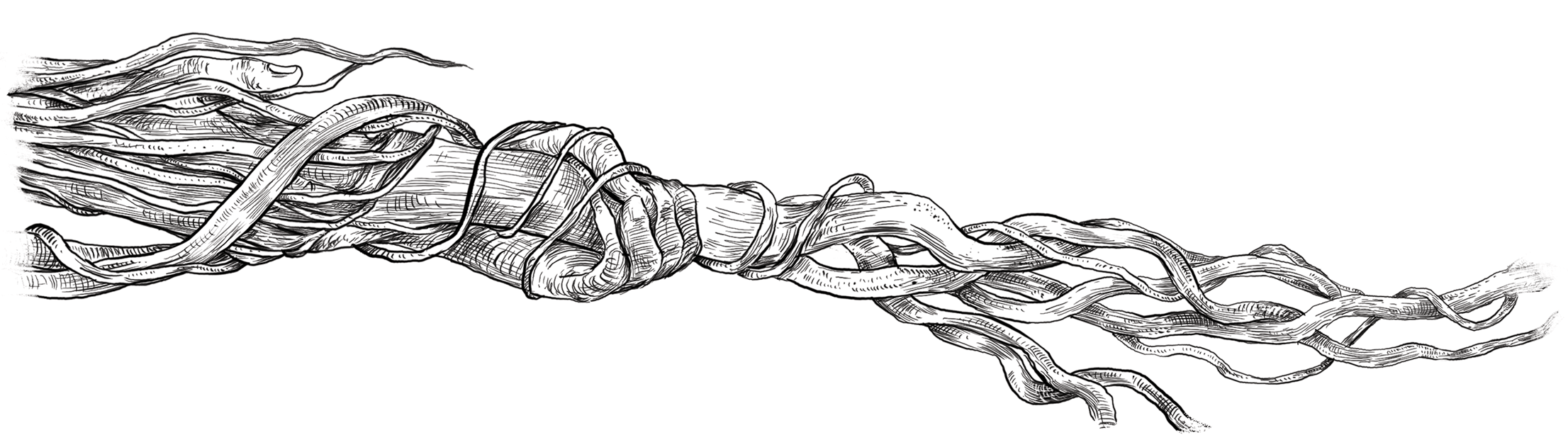

Braided roots—some as thick as a thigh, others still slender and pale—stretched 53 meters across a river gorge, anchoring from one bank to another. They coiled and twisted through the air like something alive–because they were. This was no ordinary structure. It was a living root bridge—a marvel of bioengineering shaped by hand over decades, even centuries, using the aerial roots of Ficus elastica trees. What began as a sapling on either side of the stream had been trained, over generations, into this span. No nails. No cement. Just bamboo scaffolds and time.

Together, they formed a span that felt less like infrastructure and more like the forest folding in on itself to offer passage. And it didn’t look out of place. It belonged—as much as the trees, the stones, the water flowing below.

“This one,” said a voice ahead of me, “is still learning to walk.”

Morningstar Khongthaw was crouched near the bridge’s edge, touching a pale, new root lashed to the bamboo guide. He pointed a few steps further to an older, hardened line of root now fused deep into the body of the bridge. “That one, maybe 300 years. We don’t build them. We raise them.”

Barefoot and slight in frame, Morningstar moved with the precision of someone who knew every knot and creak. He walked slowly, talking as he went—explaining how roots are selected, how they’re fed with compost from the forest floor, how each one is trained over monsoons and winters, checked, re-checked, then left to grow in their own time.

He wasn’t a scientist or a civil engineer. He was something else. A conservationist. A campaigner. A guardian of knowledge that barely exists on paper but lives in the hands and memory of a fading generation.

“I was six when I crossed this bridge for the first time,” he said. “Back then, it was just one root and two bamboo poles. My father carried me on his back.”

Now, he’s the one guiding new roots across. And with them, perhaps, a new generation.

Morningstar Khongthaw has staked his life on protecting them. What does it take to keep a bridge alive in a world that prefers speed over seasons?

And why has he staked his life on protecting something that takes 25 years to grow strong enough to hold a human?

That’s the story this walk would begin to answer.

As India nears its 100th year of independence, plans for highways, smart cities, and bullet trains dominate its future narrative. But in the hills of Meghalaya, another blueprint persists—one built not on concrete, but on roots. For generations, the Khasi and Jaiñtia tribes have grown bridges, not built them—living structures coaxed from rubber fig trees, shaped by hand over decades, passed down like heirlooms. But that inheritance is at risk. Tourism moves faster than the roots. Policy arrives from the top down. And the knowledge—passed barefoot through forests, from uncle to nephew—is fading.

Morningstar Khongthaw, a 29-year-old Khasi conservationist, is trying to hold the line. His story isn’t just about preserving tradition. It’s about whether we still know how to grow anything that lasts.

“Root bridges are perhaps one of the most elegant examples of ecological intelligence and cultural heritage intertwined,” says Sameer Shisodia, CEO of Rainmatter Foundation, which supports community-led conservation projects across India. “Morningstar’s careful approach shows us that meaningful innovation often lies in quietly enhancing traditions rather than forcing external solutions.”

“A single tree is a forest,” Morningstar said. “Imagine if we had more.” He sees the Ficus not just as a structure, but as an anchor and climate shield. “They help the water table, prevent landslides. Even a lone Ficus supports life—birds, squirrels, insects, people.”

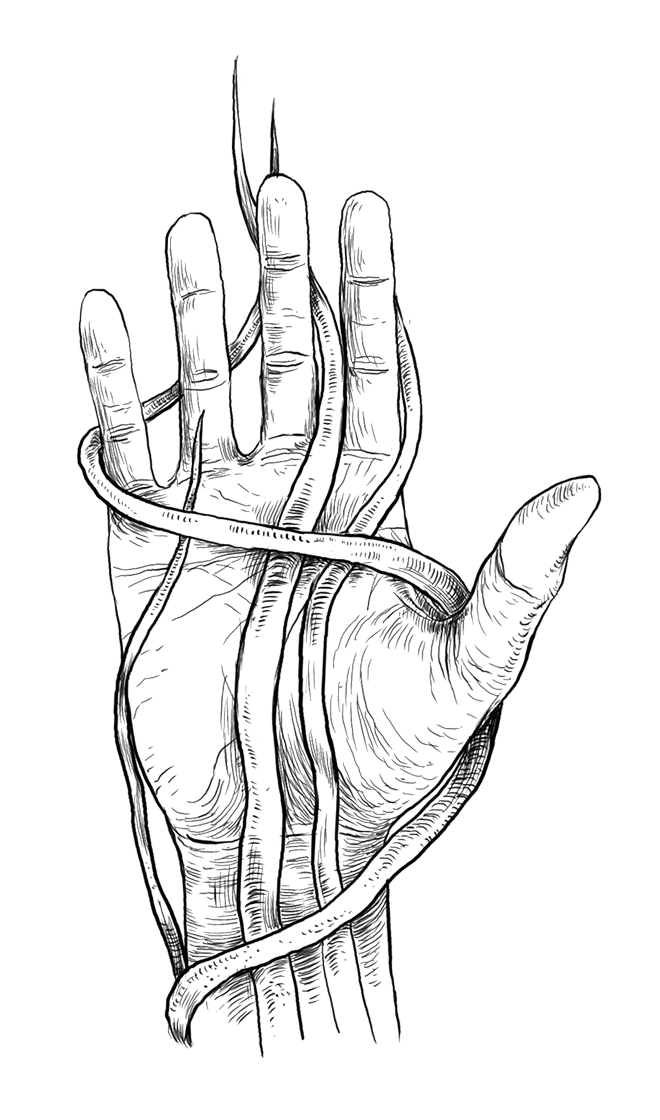

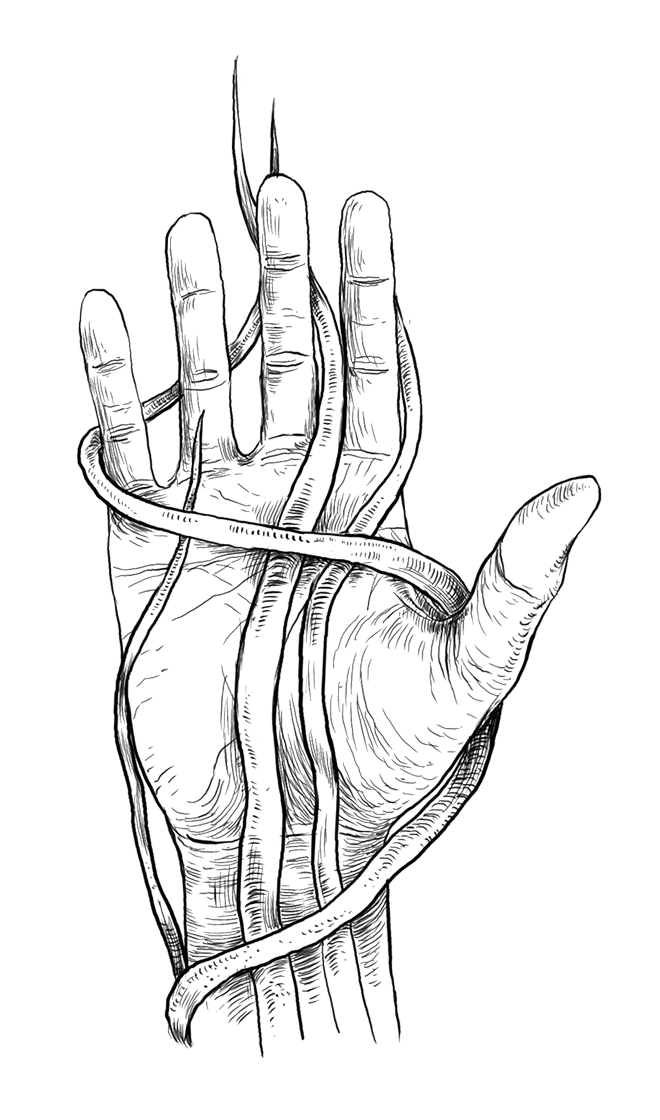

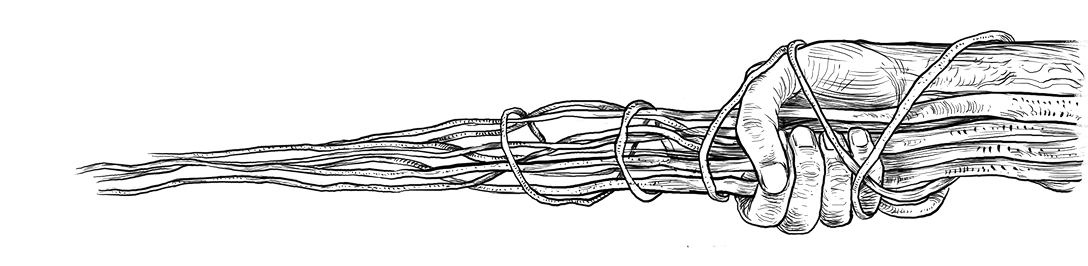

Morningstar Khongthaw ties a young aerial root to a bamboo guide during the monsoon, when roots soften “like jelly.” Guides are replaced annually as they rot; the root will be checked each season until it fuses into the structure.

The First Crossing

Morningstar was six the first time he crossed a root bridge.

“There was only one root,” he said. “One root, and two bamboo poles on either side.” He clapped his hands, gently. “That was the bridge.”

It wasn’t a full crossing—just a single aerial root strung like a tightrope across a gorge, with bamboo tied to the sides for balance. The river that carved through Rangthylliang churned far below. The bridge swayed under weight. It held, barely.

“My father carried me on his back,” Morningstar said. “We crawled together, slowly, on the living root.”

He didn’t understand what it was then—only that it was the way across. “I asked him, ‘What is this?’ He said, ‘We have to cross this to reach the other place.’ As simple as that.” The height terrified him. “Very scary,” he said. “If the root broke, we’d fall.”

That bridge still stretches across the gorge—but now it’s no longer a single line. It has thickened, matured. Morningstar has added three or four new roots, each guided over time until they fused into the structure.

Now others cross it without hesitation. But he still remembers that first crawl: the way the root trembled, the river’s sound below, and the strength of being carried.

It wasn’t a marvel then. It wasn’t beautiful. It was necessary.

It was the only way across.

Root bridges are just one expression of a wider tradition. Depending on the terrain, Morningstar and his community shape living ladders up cliffs, tunnels through the forest, and even swings woven into the canopy. “If it’s a rock face,” he said, “we don’t need a bridge. We build something to climb.” In some places, the aerial roots become scaffolds for play—suspended like vines from a Tarzan story. “It’s not just engineering,” he said. “It's an adaptation.”

A single bridge can take 25 years to mature, and once formed, it only grows stronger—some lasting centuries. Today, more than a hundred of them exist across the Khasi and Jaintia Hills, many unnamed, passed down like heirlooms.

The First Crossing

Morningstar was six the first time he crossed a root bridge.

“There was only one root,” he said. “One root, and two bamboo poles on either side.” He clapped his hands, gently. “That was the bridge.”

It wasn’t a full crossing—just a single aerial root strung like a tightrope across a gorge, with bamboo tied to the sides for balance. The river that carved through Rangthylliang churned far below. The bridge swayed under weight. It held, barely.

“My father carried me on his back,” Morningstar said. “We crawled together, slowly, on the living root.”

He didn’t understand what it was then—only that it was the way across. “I asked him, ‘What is this?’ He said, ‘We have to cross this to reach the other place.’ As simple as that.” The height terrified him. “Very scary,” he said. “If the root broke, we’d fall.”

Morningstar Khongthaw ties a young aerial root to a bamboo guide during the monsoon, when roots soften “like jelly.” Guides are replaced annually as they rot; the root will be checked each season until it fuses into the structure.

That bridge still stretches across the gorge—but now it’s no longer a single line. It has thickened, matured. Morningstar has added three or four new roots, each guided over time until they fused into the structure.

Now others cross it without hesitation. But he still remembers that first crawl: the way the root trembled, the river’s sound below, and the strength of being carried.

It wasn’t a marvel then. It wasn’t beautiful. It was necessary.

It was the only way across.

Root bridges are just one expression of a wider tradition. Depending on the terrain, Morningstar and his community shape living ladders up cliffs, tunnels through the forest, and even swings woven into the canopy. “If it’s a rock face,” he said, “we don’t need a bridge. We build something to climb.” In some places, the aerial roots become scaffolds for play—suspended like vines from a Tarzan story. “It’s not just engineering,” he said. “It's an adaptation.”

A single bridge can take 25 years to mature, and once formed, it only grows stronger—some lasting centuries. Today, more than a hundred of them exist across the Khasi and Jaintia Hills, many unnamed, passed down like heirlooms.

AT A GLANCE

Ficus elastica — the tree behind the bridges

Species

Ficus elastica (Indian rubber fig)

Native range

India, Nepal, Bhutan, Myanmar, Southeast Asia

Growth habit

Produces aerial roots that descend from branches, thicken with age, and can be trained into load-bearing structures

Strength

Mature inosculated roots develop tensile strength comparable to softwood beams; strength increases with age rather than declines

Timelines

~10 years: bridge can begin to bear light weight

~25 years: span stable for daily use

~50+ years: structure fully mature; can last centuries

Timelines

~10 years: bridge can begin to bear light weight

~25 years: span stable for daily use

~50+ years: structure fully mature; can last centuries

The Tree Named Morningstar

He was born just before dawn. “Four a.m.,” Morningstar said, smiling. “Still dark.”

His mother gave him the name.

She was the only educated woman in their village then—Rangthylliang, tucked deep in the East Khasi Hills. “She decided to give her name Morningstar,” he said. “So that’s how I got mine.” On paper, in school, everywhere: Morningstar.

There’s a certain inevitability to the name now—but it didn’t always fit.

As a child, he was restless. He went to school like the others, stood in the prayer assembly in the mornings, looked at the walls, the rules, the textbooks. “I ran away,” he said with a laugh. “When I saw my father outside, I just left. I walked out of school.”

He wasn’t reprimanded. “He never scolded me,” Morningstar said. “He always made the decision positive, whatever I chose.”

That freedom stayed with him. It took shape in books—but not in the way school prescribed. “I wasn’t good at writing,” he said. “Or learning, you know, the formal way.” But when he liked something, he read it cover to cover. “That’s how I passed,” he said. “Just read the whole book.”

He made it to eleventh standard in Shillong. “But I left after three months,” he said. “The books were too much. I told my mother: "I don't want to be unemployed at the end of this road.”

She didn’t speak to him for six months.

He left anyway.

“I just wanted to find something else for me,” he said. “Not everyone needs to follow the same path.”

He began walking different ones—in the forest, between villages, toward people and places no curriculum ever mentioned. Those wanderings became his education. He met elders. He learned the old ways—not taught, but shown. The bridges. The trees. The reasons why they mattered.

And he started to imagine something else—not for himself, but for the village he had left and returned to.

DESIGN.

BUILD.

GROW.

The root bridges of Meghalaya aren’t built. They’re raised. Not with cement or steel, but with time and care passed from one generation to the next.

“First, you look at the stream,” Morningstar said. “If there are no trees on either side, you plant.”

It begins with a Ficus elastica sapling—an Indian rubber fig—chosen for its aerial roots that descend from branches and seek the ground. If the terrain allows, trees are planted on either side of the stream or gorge.

“Two is best,” Morningstar said. “That way, the roots meet faster. If it’s only one tree, it takes longer.” Once the trees are in place, the waiting begins.

In the rainy season, when the roots are soft — "like jelly," Morningstar said — they are gently bent and guided across the span using bamboo scaffolds, hollowed areca palm trunks, or ropes. The bamboo structures are replaced annually as they decay. The roots are lashed in place with whatever is available: natural fibers, plastic cords, even aluminum wire.

“You don’t touch the roots too early,” he said. “They’ll snap. Three or four months old, they’re too fragile. One or two years—that’s when they become candidates.”

Guiding the root is not a one-time action but a sustained relationship. The team returns each monsoon to weave, check growth, replace bamboo, and feed the roots — not with fertilizer, but with forest compost. “Rotten leaves, branches, old wood,” Morningstar said. “We place it under the root like you’d place money for something precious. That’s how we feed it.”

There are no blueprints. No manuals. “One uncle to another,” he said. “You grow up near a bridge, you start helping.”

He pointed to a pale root tied to a guide. “Five or six years,” he said. “Then it will touch.”

Even once complete, a bridge is never finished. It may take ten years before it holds weight. Twenty-five to be strong. Fifty to endure.

“We don’t stop weaving,” Morningstar said. “Even after you walk on it. Even after it holds.”

Every bridge is a collaboration—not just between roots, but between people. One person starts. Another finishes. “It’s inheritance,” he said.

In Khasi myth, there’s a golden bridge of roots—jingkieng ksiar—that once linked earth to heaven. Morningstar doesn’t elaborate. He only gestures toward the trees.

“It’s in the stories,” he said. “But mostly, it’s in the roots.”

Some bridges don’t fall. They fade. “When a bridge grows weak, we plant a young Ficus on top of the mother tree,” Morningstar said. “So when she dies, the child is already growing.” Even endings, here, are designed to carry on.

The old stories weren’t instruction manuals, but they seeded something just as enduring—an intuition passed down not through diagrams, but through doing.

IN PRACTICE

How living root bridges are kept alive

Seasonal tending: Monsoon is the key period. Roots soften and are guided across scaffolds; teams return each year to adjust lashings and check growth.

Bamboo scaffolds: Temporary frames; rot within a year, forcing replacement and continual care.

Feeding roots: Beds of forest compost—rotted leaves, branches, wood—placed beneath guided roots for moisture and nutrients.

Innovation: Some weavers now use dark irrigation pipes. The enclosed space creates humidity and shade, speeding early root growth.

Never finished: Even after a bridge carries people, new roots are woven in, weak strands retired. A bridge is always in progress.

The Promoter Who Became a Guardian

When Morningstar first returned to Rangthylliang from Shillong, he saw the bridges differently.

Shillong exposed him to new ideas—unfamiliar people, different rhythms, what he called “great minds.” It was brief, but it stayed with him.

In 2013, a Doordarshan crew arrived in Rangthylliang to film the elders and their stories. Morningstar was asked to help. “I was just a student,” he said. “But that’s how it started.” For the first time, he saw the bridges through a different lens. They weren’t just crossings. They could be destinations.

Other places were already being promoted—the double-decker in Nongriat, the one in Molnau. “I thought maybe we could do the same here,” he said. “Bring people. Show them.” He thought he could be a promoter. But the more he explored those tourist sites, the more unsettled he became. The noise. The footfall.

He saw bridges roped off, rotting under crowds who came for photos, not stories.

“It became a turning point,” he said. “Before we promote, we need to learn how to protect.”

He began asking different questions. What happens when a root is stepped on a thousand times? When a bridge that took 50 years to grow snaps in a single monsoon?

He started visiting elders again—not for folklore, but for instruction. How did they guide the roots? How did they feed them? “I learned the Ficus is a keystone tree,” he said. “One tree supports many others. Even animals.”

Slowly, the bridges stopped being landmarks in his mind. They became archives. Living structures. “We grow them with our hands,” he said. “It’s not construction. It’s conservation.”

So he turned around.

From a boy chasing a tourism dream to a fierce conservationist. “I wanted to protect what we still had,” he said. “And protect it the way it was meant to grow—slowly, patiently, from the roots.”

Then one night, a bridge fell.

The Night the Bridge Fell

Morningstar remembers exactly where he was when the news reached him. It was late evening, sometime in August or September 2018—he isn’t entirely certain of the exact day, but he clearly remembers the elder who brought him the news emerging from the forest path, weary and heavy with concern. They met quietly, standing at the edge of the village, as shadows lengthened across the hills.

“I couldn't sleep the whole night,” Morningstar recalled, the emotion still fresh, years later. “I kept thinking about the tree. I woke up with a heavy heart and went to find the old man who brought me the news.”

In the early morning, he walked to the elder’s modest home in the village. Together they sat, sharing tea and sadness, reflecting on the sudden loss. They talked about the bridge—the roots carefully guided for years, now severed overnight. The elder explained gently: the tree belonged to an old man named Ba-Bli Khongthani, who lived bedridden and frail in Pynursla, nearly 90 years old. Ba-Bli had purchased the tree around thirty years earlier, sometime in the late 1980s, for just sixty rupees from an old village woman—a small, almost symbolic sum against the significance of what had been lost.

Morningstar knew what he had to do. Returning home that day, he began meticulously drafting a handwritten agreement—his very first—to formally transfer ownership of the tree. “I personally wrote that agreement,” he said later. “I got it typed immediately because I didn't want to waste his time. He was old; he was sick. It felt urgent.”

Later that evening, as the sun dipped behind the dense forest hills, Morningstar gathered two companions: the village elder who brought him the news, and Willem Betts, his tall Canadian friend who had been staying with his family for the past fifteen days. Together, carrying lanterns, they walked slowly along the path toward Ba-Bli’s small home in Pynursla.

Inside the humble dwelling, Ba-Bli lay on his bed, weak but alert, his wife and daughter seated close by, uncertain about their late-night visitors. Morningstar knelt near Ba-Bli and spoke gently. He described his vision for the tree—not just protecting it but nurturing it as a symbol and inheritance for future generations. Ba-Bli listened, nodding softly, his eyes thoughtful.

After a pause, Ba-Bli broke the silence. “In fact,” he said softly, “I would be very happy to hand it over to someone who could take care of my tree.” He remembered aloud the modest transaction decades earlier: “I bought it thirty years ago, from an old lady, for sixty rupees.” He paused again, smiling faintly. “If you really want to take care of the tree, then it's yours.”

Without ceremony, Morningstar presented the agreement. Ba-Bli motioned, indicating Morningstar should sign. Morningstar quickly signed the document, his Canadian friend Willem Betts adding his name as a witness, alongside Ba-Bli’s relative from the village. The paper—typed hastily earlier that day on a simple A4 sheet—carried the date clearly marked in Morningstar’s own handwriting: August or September 2018 (later, he would laminate this precious document, carefully preserved like a sacred heirloom).

When Morningstar left Ba-Bli’s home that night, stepping back into the darkness of the forest, he felt a profound sense of relief. Yes, a bridge had fallen—but ownership had passed from one generation to another.

“It’s a living book for me,” Morningstar later said of that laminated page. “Something I can hold, something I can protect.”

And something he could grow again.

Dibanson Marbaniang, who works with conservationist Morningstar Khongthaw, stands by a 200-year-old ficus tree passed down in his family.

The Avatar Tree

Morningstar still remembers the first time he stood beneath it—the giant Ficus tree casting its own weather, the light shifting in its branches.

“It was going to be cut for charcoal,” he said. “The old man was ready to sell it off.” The tree was over 400 years old. Its aerial roots had been guided into two working bridges, he later found. It had sheltered generations. But the family that owned it needed money. And the deal was nearly done.

“I couldn’t let it go.”

He borrowed ₹5000 from a friend. “That’s all it cost. A sacred tree. A living bridge.” The transfer wasn’t formal—no paperwork, no documentation. Just a conversation. Just intent. The old man handed it to him the same night. “Now it’s yours,” he said.

For Morningstar, it wasn’t just a tree. It was an inheritance. A lab. A commitment.

“I started dreaming about it,” he said. “Not just to protect it. But to build something inside it. A root nest. A hut in the canopy. Something that shows what’s possible.”

He calls it his Avatar Tree.

The canopy now hosts a bamboo ladder that rises into the branches. Morningstar built it with his team—a vertical scaffold, temporary, handmade. It collapsed once during the lockdown. He plans to rebuild it. Slowly. Properly.

This time, the roots won’t be guided down into a bridge. They’ll be shaped inward—into a circle.

“Not for people to look at,” he said. “For us to stay. Sleep. Live in.”

Mystics in the village believe the tree is more than shelter. They say it carries messages. When someone is about to die, a whisper comes. Or the sound of a baby crying—heard through the roots.

Morningstar doesn’t dismiss the stories. He just listens. “If you grow up here,” he said, “you learn not to separate spirit from soil.”

The Avatar Tree became a monument not to ownership, but to care—and to choice. Where others saw timber, he saw time.

“I wasn’t gifted land, or money,” he said. “I was gifted a tree.”

So far, Morningstar has mapped 133 bridges across Meghalaya. “Still more to discover,” he said. Many remain unnamed, tucked inside forests only elders still remember.

The Mentor Who Climbed Barefoot

Jalong Khomola rarely wore shoes. Even into his seventies, he moved barefoot through the Khasi forests, scaling tall ficus trees to gather saplings, each destined to become a bridge. “He dedicated his whole life to root bridges,” Morningstar recalled. “Barefoot, always climbing trees, always guiding roots.”

Their relationship began in 2015, at village meetings or near Khomola’s orange orchard close to Morningstar’s newly acquired tree. Morningstar often found himself interpreting for foreign visitors who came to see the bridges. Khomola, patient and gentle, would explain the slow art of weaving roots into bridges—stories passed from elder to younger, like whispers through generations.

In 2018, Morningstar received his first public award for root bridge conservation. He invited Khomola as a guest of honor. Khomola stood on stage barefoot, accepting recognition humbly—almost reluctantly. A photo of that day still remains with Morningstar, a cherished keepsake.

But in October 2022, tragedy struck. Khomola, then nearly eighty, fell from a tree while picking jackfruit. The impact shattered his thigh. Doctors at the hospital warned the injury was severe enough to require amputation. Morningstar resisted fiercely: “I told him we have to trust traditional healers instead. The doctors would just cut; our healers would save him.” He rallied friends, raised funds, and helped arrange for traditional treatment. Slowly, Khomola healed. But the injury weighed heavily on him. Restless without his forest, he dragged himself daily through the village, struggling but determined to keep moving.

When Khomola passed away shortly afterward, Morningstar stood at his funeral, heart heavy and voice strained. “I couldn’t speak much,” he said, remembering the moment months later. “It hurt too much to talk about him.”

Yet Khomola’s legacy endured, alive in every root bridge Morningstar touched. Especially in one innovation that Morningstar learned from his mentor: using plastic irrigation pipes instead of open bamboo scaffolds. Khomola had discovered the pipes, dark and enclosed, encouraged roots to grow faster. Tradition had silently embraced innovation.

Today, Morningstar continues that practice, blending old knowledge and new tools, feeling the presence of his barefoot mentor with every root he guides.

RESPONSIBLE VISIT

If you go, tread like a guest, not a consumer

Go small, go slow: Visit in small groups, off-peak hours. Avoid peak monsoon stress.

Step wisely: Walk only on mature decks. Never tread on pale or loosely tied roots.

Footwear: Shoes with grip but no spikes. Don’t lean poles or tripods on living roots.

Noise & conduct: Keep voices low. No music playback. Drones only with community approval.

No shortcuts: Don’t ask locals to cut new paths or speed root guidance for visitors.

Compost gifts: Only if invited—natural fiber or compost. Never add materials yourself.

Respect privacy: Ask before photographing residents. Avoid geotagging exact sites.

Support locally: Hire guides, pay fees, buy food or tea in the settlement rather than carrying packaged goods.

Battles in the Forest

Not every bridge is lost to time. Some are undone by belief.

Morningstar still remembers the morning after they built the bamboo scaffold—twenty villagers working shoulder to shoulder through the day, coaxing young roots into position, tying, tucking, guiding. By dawn, it was gone. Cut down at night.

“The uncle didn’t want it near his farmland,” Morningstar said. “He thought it would curse his crops.” No warning. Just an undoing.

In another clearing, a half-grown bridge collapsed after a feud between neighbors—two families, one bridge, and an argument no one could resolve. One night, one of them ended it by ending the bridge.

The reasons vary—belief, boundaries, old resentments—but the outcome is the same. Roots once tended by hand, left severed in the soil.

Morningstar doesn’t argue. He returns with stories. He sits with the elders, brings tea, and waits. Then he asks, simply: “What did the bridge do wrong?”

He reminds them to watch the forest more closely. How roots seek each other, not apart. How they grow stronger by holding. “The bridge never divides,” he says. “It connects.”

His original team of thirty has thinned to five. “Many left,” he said. “Some needed jobs. Others wanted faster change. This work doesn’t offer either.”

Those who stayed, stayed with their hands. They gather roots, replace scaffolds, count seasons. No shortcuts. No promises. Just care.

In 2022, the monsoon came early. Rivers swelled. Paths vanished. Five bridges were lost—washed away, roots torn from their anchorings.

Morningstar didn’t mourn. “When a bridge falls,” he said, “you don’t ask why. You start weaving again.”

Defending the Roots

In 2019, the government came with paperwork and plans.

A proposal to include Meghalaya’s living root bridges on UNESCO’s tentative list had begun moving through bureaucratic channels. On the surface, it looked like recognition. To Morningstar, it sounded like a warning.

“They were calling it a top-down approach,” he said. “But these bridges are not top-down. They are root-up.”

The blueprint barely involved the people who raised the bridges—who still guided roots each season, replaced scaffolds each year, remembered which ancestor planted which tree. No elders were consulted. No weavers invited. “How can you write policy,” he asked, “if you don’t even know what inosculation is?”

What troubled him wasn’t heritage recognition—it was how it was imposed. A template from elsewhere, dropped onto a landscape with its own rhythm, its own sacred groves, its own rules.

“We already had rules,” he said. “Our clans made them in 1939. You cut a tree, you paid a fine. We didn’t wait for UNESCO to tell us what was sacred.”

He refused to endorse the plan. Instead, he gathered elders, youth, and landowners from eight clans. Some were hesitant. Others feared missing out.

He asked them to look at the bridges—not just the roots, but the way they grow. “No root dominates. No hand forces. We all weave.”

To make his point, he referenced a story every Khasi child knows—the golden root bridge, jingkieng ksiar, that once connected earth to sky.

“This isn’t tourism,” he said. “It's a memory. It’s instruction. It’s ours.”

Officials called him difficult. Some said he was politicizing trees. But Morningstar wasn’t against recognition. He was against erasure.

“We don’t want fences,” he said. “We want responsibility. That’s what makes a bridge last.”

The Hundred-Year Vision

The Hundred-Year Vision

In the hills above Rangthylliang, Morningstar bends over a sapling barely a foot tall. Its roots are tentative, unsure of their place in the soil. Around it, bamboo scaffolds rise like skeletal bridges-in-waiting—a signal that this patch of forest has been claimed not by extraction, but by intention. This is where Project 2047 begins.

“It takes 25, maybe 30 years,” Morningstar said, brushing dirt from the young Ficus stem. “So we start now. When India turns 100, these bridges will stand.”

The idea began as a way to preserve root bridges in a time when both memory and patience were running out. Over time, it hardened into a blueprint: thirty bridges, planted and raised with the help of village elders, students, and barefoot engineers. No cement. No contracts. Just a living vision of what infrastructure could mean. By the time most government projects break ground, these roots will already be growing.

Each season brings its own rhythm. Monsoon is for weaving—when aerial roots soften and can be gently bent into place. Winter is for replacing bamboo, checking growth, and keeping the forest healthy. It’s not just planting trees. It’s building bridges without blueprints—relying on time, touch, and trust.

Morningstar calls it design, build, grow. A phrase he repeats often, sometimes to schoolchildren with wide eyes, sometimes to funders skeptical of a project whose return lies decades ahead.

“The bridge doesn’t belong to me,” he said. “It belongs to the child who will cross it when I’m gone.”

Project 2047 is not just about bridges. It’s about reviving Law Kyntang—sacred groves protected by community law and oral memory. In these forests, Morningstar says, “we don’t walk in with shoes. We don’t speak loudly. Even the trees listen.”

Morningstar calls it design, build, grow. A phrase he repeats often, sometimes to schoolchildren with wide eyes, sometimes to funders skeptical of a project whose return lies decades ahead.

“The bridge doesn’t belong to me,” he said. “It belongs to the child who will cross it when I’m gone.”

Project 2047 is not just about bridges. It’s about reviving Law Kyntang—sacred groves protected by community law and oral memory. In these forests, Morningstar says, “we don’t walk in with shoes. We don’t speak loudly. Even the trees listen.”

He’s working with local schools—encouraging students to adopt nearby bridges, guiding them through root weaving, asking them to track growth and sketch what they see.

“Not everyone will stay,” he said. “But some will. And that’s enough.” He walks the hills almost daily—sometimes alone, sometimes with visitors, often with a bundle of bamboo tied over his shoulder. He greets elders. He checks saplings. He listens.

Project 2047 is a slow defiance in a world too quick to build and too reluctant to care. “When they ask what development looks like,” Morningstar said, “we can point to this. A root in the ground. A bridge above a river. Still growing.”

Traditionally, only old, unmarried men were allowed to plant Ficus trees. “You had to be over 50, with no daughters or sisters,” he said. Morningstar ignored all of it. “Belief is important,” he said. “But belief in yourself is more important.” He planted 25.

A Promise Beneath the Feet

In the soft light of late afternoon this May, Morningstar stepped once more onto the living bridge. The roots held him—not just as structure, but as memory and belief. “I’ve been walking here more than twenty-two years now,” he said. “But I started caring for it later.”

He pointed to a young root guided along a bamboo scaffold. “This one, I weaved in 2021. Still learning.”

Each root on the bridge had passed through someone’s hands. And those hands, like his, belonged to people who never trained as engineers—but who carried an inheritance. “You don’t build a root bridge,” he said. “You raise it like a child.” Now the child was growing up.

He has already planted 25 saplings—ignoring customs that said only old, unmarried men should do so. “Belief is important,” he said. “But belief in yourself is more important.”

There were setbacks. Bridges cut down in feuds. Volunteers who left. A landscape filled with fault lines. But he stayed. “We should learn from the bridges,” he said. “So many hands, so many knives, all making one thing.”

At the edge of the bridge, he paused.

“In 2047,” he said, “our country will be 100. I want our root bridges to still be here. Stronger. With more roots. More hands.”

A single root dangled nearby, just beginning its descent. Morningstar watched it for a moment.

“This is not just a bridge,” he said. “It’s a promise.”

“My legacy,” he added, “is not just the bridges I build. It’s the belief that young people can shape tradition. That we don’t have to wait until we’re 50 and alone to start planting trees. We can begin now—and someone else will finish.”

When I Close My Eyes

Every night before sleep, Morningstar sees bridges—not just as structures, but as ideas, patiently nurtured and handed from one generation to the next. He sees roots inching forward, guided and measured. Elders weaving alongside restless youths. Schoolchildren with notebooks, documenting traditions once kept only in memory.

“People called me mad,” he said with a faint smile. “They asked why I teach students to weave roots. But every night when I close my eyes, I still see them there.”

There is frustration too—borne from years of hollow reports and fleeting academic curiosity. “I’m fed up with verbal reports from elders becoming someone’s PhD thesis,” he told me. “I want real research. One-foot roots, measured, timed, documented.”

Then, almost in a whisper, he shared a dream: “My wildest imagination is creating my own living root shelter—a nest, inside a tree. My own.”

But even as he spoke of ownership, his voice circled back to an older lesson: “No one can own a root bridge. You can own a tree, yes. But never the bridge.”

In the end, that is what lingers: his clarity that the true measure of what he is building will outlast him. Bridges grow slowly—beyond lifetimes, beyond single generations—and are never truly owned by anyone.

They are promises made by one generation to the next.

In the end, that is what lingers: his clarity that the true measure of what he is building will outlast him. Bridges grow slowly—beyond lifetimes, beyond single generations—and are never truly owned by anyone.

They are promises made by one generation to the next.

WHAT ENDURES

Bridges are raised, not built. They grow stronger with each season, shaped by hands and time, not cement.

Roots need tending. Pale aerial roots are guided, checked, and fed every monsoon until they fuse into the span.

Ownership is not stewardship. A tree can be bought, but a bridge endures only when many people choose to care for it.

GLOSSARY FOOTNOTES

- Aerial root — A root that emerges from a stem or branch and grows toward the ground; in Ficus elastica, these can be trained and fused to form load-bearing structures.

- Inosculation — The natural fusion of plant tissues when roots or branches are held in contact long enough; the basis for turning multiple guided roots into a single member.

- Ficus elastica — Indian rubber fig. Evergreen tree native to parts of South and Southeast Asia. Valued in the Khasi and Jaintia Hills for strong, trainable aerial roots.

- Living root bridge — A pedestrian crossing shaped over years from Ficus elastica aerial roots guided over a stream or gorge using temporary scaffolds. Strength increases with age.

- Law Kyntang — Community rules protecting sacred groves in Khasi areas; typically ban cutting, loud conduct, and extractive use inside designated forests.

- Jingkieng ksiar — “Golden bridge” in Khasi; a traditional story about a root bridge that once linked earth and sky.

- Pynursla (pronounced: pin-UR-sla) — Subdivision in Meghalaya’s East Khasi Hills; includes villages known for living root bridges, such as Rangthylliang and Mawkyrnot.

- Keystone tree — A species that disproportionately supports an ecosystem; Ficus species provide food, habitat, slope binding, and water-table benefits.