As online harassment explodes in India, the world’s second largest market of internet users, local police and judiciary struggle with the new-age crime — even if it ends in a suicide

Linkan Subudhi was on cloud nine on the morning of May 29, before her political career nosedived.

It was the day after the state level conference of the Biju Janata Dal’s (BJD) youth wing at Bhubaneswar. As a general secretary of the youth wing, she had worked hard to launch a campaign to enroll 20 lakh members. Chief Minister Naveen Patnaik inaugurated the drive, and her work was well appreciated.

So when Saroj Behera, a reporter from Zee Kalinga called her up around 10 am, Subudhi was quite cheerful.

“Linkan Ma’am, I have seen a picture of you on a website.”

Subudhi replied with a laugh, thinking he was indulging in some good-natured ribbing.

“Okay, there was a party meeting yesterday. You might have seen that picture.”

“No, it’s something else. It’s to do with escort services.”

“What is this website,” she asked.

Behera told her that it was in the personal section of a classifieds website Locanto. He hung up and landed at Subudhi’s house. On a laptop, he showed her the post.

The post was featured in the category “Women Looking for Men – Balianta.” Balianta is a suburb on the east of Bhubaneswar, separated from the city centre by the Daya river.

The post title summarises a few intimate massage services provided by a 22-year-old “Sex Girl Reema.” Below it is a picture of Subudhi.

The setting is a balcony of an apartment with potted plants around her. She’s sitting in profile, wearing a pink cardigan, with her face turned to the camera. Her hands rest on her lap, and she has a faint smile. An innocuous picture, one that could have been used as a profile photo.

Below the photo is a message.

“Hi myself Reema,” the post begins and states that she is 22 years of age (Subudhi is 33 years old). She’s staying “independently alone in her house,” and she’s available for all types of service.

It’s followed by a sexually explicit list of massage services. A mobile number with an appeal to call ‘Reema’ follows. The last line restates her age — 22 years.

Behera told FactorDaily that a friend who frequented online classifieds website like OLX and Quikr came across this post while searching for deals in Bhubaneswar. He recognized Subudhi and forwarded the post to Behera.

At the time she saw the post, Subudhi says, she was unaware that she had any detractors. But she suspected that her quick rise in the party had left a few disgruntled.

In 2013, Subudhi rose to fame as she nearly died while trying to prevent a child marriage in Noida. She received a call from a girl she taught while volunteering at a slum. The girl asked her to rescue her from a wedding.

When she reached the slum, the girl’s mother and a man (who was to marry the minor) attacked Subudhi with sticks and knives. She was hospitalized and received more than 30 stitches on her head. Even today, she suffers headaches from the injuries.

The police rescued the girl, and Subudhi moved back to her home state Odisha where she’d become a household name.

The reception on her return was rapturous. “She’s our Malala,” says Namrata Chadha, a child rights activist and Subudhi’s mentor, referring to the Pakistani Nobel laureate who was also attacked for her campaign for girls’ education.

Chief minister Patnaik was an early champion of Subudhi. He presented to her the Biju Patnaik bravery award, the first in several years.

His party, the ruling BJD, gave her a ticket in the Bhubaneswar Municipal Corporation elections. She was in contention for the mayor’s post but lost the election. Then, the party appointed her as a general secretary of the youth wing. They were grooming her for the assembly elections in 2019.

“In a very short period, I am at a level which would take most people a decade,” she says.

It was likely that someone from the party was responsible for the post on Locanto.

There was one glaring clue: the phone number mentioned in the post. When Behera checked the number on Truecaller – a phone app that lets you reverse look-up numbers to names – it revealed a name. Surya.

Neither Subudhi nor Behera knew who this person was.

Subudhi called Chadha, and they visited Satyabrata Bhoi, the Deputy Commissioner of Police (DCP) Bhubaneswar. She showed him the post. Chadha recalls that the DCP’s approach was “really very good”.

Subudhi and Chadha felt that the DCP was aware of similar such cases and within 3-4 minutes, he had a lead. He showed the Facebook profile of a man to Subudhi and said he might be the culprit.

Subudhi lodged an FIR and addressed an email with screenshots to the DCP. He told her that the inspector-in-charge of her local police station would contact her.

Later in the evening, around 4 pm, Subudhi met Inspector Deepak Kumar Mishra. Together they drafted an email to Locanto’s support email ID informing them of the offending post. “This has defamed her personality and social dignity. This is related to the life and dignity of women(sic)…”.

A three-point action plan followed. First, to remove the post including the photograph. Second, to provide details of identifiable information such as IP and MAC addresses of the advertiser. And third, to share details such as date and time of posting, the location of the advertiser, and any information to aid the investigation. The email was sent at 6 pm.

By then, Behera had telecast the story on Zee Kalinga, and the story shot to the top of the Odia news cycle. News channels began putting it on scrolling tickers. Subudhi began to receive several calls.

Subudhi told them that about the post. “I told them that I needed to fight because there were many similar cases… So many innocent people were being harassed. They don’t even know that they are in a trap. So I want to fight for that,” she says.

Subudhi met her advocate, who advised her to let the police continue their investigation. As the day wore on, Subudhi hadn’t spoken to her family. News had reached her village near Puri, and people began calling up her family. “That there is some sex website where Subudhi’s picture is put up. They were scared,” she says.

“They called me, but I was in the middle of fighting, finishing the formalities, driving to various offices, documenting all the pictures, and writing emails,” she recalls.

As she got back from the advocate’s house at night, she felt broken. “I pulled over, raised the windows of my car, and began crying like hell,” she says.

“I remember thinking I may win this fight. But people, who remembered the Subudhi who fought against child marriage and stood in an election; they will now think of her as someone who was on a porn website.”

Subudhi’s story is not unique, but an example of a growing new wave of online harassment. The assaulter seeks to punish or take revenge for personal or professional reasons.

They use Facebook, Twitter, or a slew of lesser-known sites such as Locanto and Gigololist to harass. They scrape photographs from Facebook, Twitter, or WhatsApp. They post defamatory content by morphing the photo, or they pose as the victim soliciting sex online. In some cases, the harassers also put up phone numbers.

Online complaint boards such as consumercomplaints.in are replete with such stories.

One victim writes that someone posted pictures of her on Locanto as a 30-year-old widow from Chennai, unable to control her “sexual feelings.” The post also lists her phone number. She complains that several people have called her for “call girl facilities.”

Another victim from Bangalore writes about receiving messages from “multiple perverts soliciting sex.” The ad listed her email ID.

A woman from Tamil Nadu lodged a police complaint after someone posted her phone number. She asks Locanto to take down the ad and verify phone numbers before posting ads. She says the ad was spoiling her reputation and giving her mental stress.

In some cases, the women targeted by these ads are relatives of business rivals. An Odia businessman found a prostitution ad using his wife’s name and Facebook profile photo. The post also listed his mother’s phone number. The ad promised a “safe and high quality service” at their home and a concession to college students.

FactorDaily reached out to a few victims. A Chennai businessman recounted an incident involving his cousin and her husband. In early 2015, the husband began receiving phone calls inquiring about charges for his wife. The frequency increased over the next few days.

On investigation, they came across a post on Locanto. It was titled “I love to sk big ck” with the husband’s phone number. Despite writing to Locanto, the advertisement remained online for a few months. Meanwhile, the calls increased in frequency. “My cousin is a mother to two college-going children. This was extremely distressing to her,” says the businessman, asking not to be identified. “This also caused a rift in the marriage.”The family suspected a business rival since the phone number was used for business. They suspected a Mumbai-based rival. The Chennai businessman and the husband confronted the rival and warned him to take the post down. Though he denied any involvement, the post was taken down in a few days. The husband stopped receiving calls. But, the Chennai couple did not approach the police. “We did not want the publicity and intrusion that a police investigation would entail,” says the businessman.

Photo: Sriram Vittalamurthy

Debarati Halder, a law researcher from Ahmedabad, has counselled cybercrime victims for a decade. She says that for most victims, the priority is to take down the content. “Pursuing and prosecuting perpetrators is only a second priority,” she says.

Like the Chennai businessman, most victims don’t take the legal route. Primarily, they need to convince the website to remove the content. And for sites based outside India, this is often the only practical route.

Take the case of Subudhi, whose picture appeared on a website based in Germany. Locanto does not have any servers in India nor does it have any offices here. So, she wrote an email to Locanto to take down the post. Two days later, it was off the website. Locanto did not respond to an email for comment.

Dr. A Nagarathna, who heads the Advanced Centre for Research, Development and Training in Cyber Laws and Forensics at the National Law School India University Bangalore, says many victims attempt this tactic first.

Often, victims get police officers or employ lawyers to write to these sites. But there’s no legal weight or force to these requests.

“The effectiveness of these methods is completely dependent on how benevolent the website is feeling. At the end of the day, it depends on whether the recipient will respect this request,” says Nagarathna.

A few websites have laid out community standards, and users can flag content that breaks them. Facebook, for instance, prohibits bullying, harassment, and credible threats of violence.

But Indian law enforcement officials find these standards opaque. A police officer from Tamil Nadu, who works on cybercrime cases, says they are a law unto themselves. “It’s really hard to understand what makes it into their standards, and what doesn’t,” the officer says.

Nagarathna says that these standards vary from society to society. “What is decent and moral according to one society may not be the same as another society. Differences in the laws between the service provider’s country and India also play a role,” she says.

FactorDaily reached out to Facebook to understand how they handle complaints.

Once Facebook receives a complaint, the Community Operations team reviews that content. “Our global team reviews these reports rapidly and will remove the content if there is a violation,” a spokesperson from Facebook says.

They claim reports are reviewed 24 hours, seven days a week, and a vast majority of them are reviewed within 24 hours.

Facebook says they have real people looking at reported content in more than 40 languages across the world. This includes more than ten in India.

“These include native language speakers because we know that it often takes a native speaker to understand the true meaning of words and the context by which they are shared,” the spokesperson says.

But language issues still persist. The Tamil Nadu police officer cited several instances when offensive content in Tamil was not taken down soon enough.

Facebook has also begun using automation to enforce some of these standards. “After someone reviews and removes a photo or video for nudity or pornography, this system may remove the same photo or video if it surfaces in other places,” the spokesperson adds. Facebook has also introduced new features to prevent people from misusing profile photos.

Big Tech companies such as Google, Facebook, and Twitter have realised that they need to tackle these issues head-on.

In May this year, after a slew of live streams and videos showed people hurting themselves and others on Facebook, the company has announced that it will be adding 3,000 people to their community operations team. This is in addition to the 4,500 that reviews reports every week.

In a post, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg wrote “These reviewers will also help us get better at removing things we don’t allow on Facebook like hate speech and child exploitation. And we’ll keep working with local community groups and law enforcement who are in the best position to help someone if they need it – either because they’re about to harm themselves, or because they’re in danger from someone else”.

Twitter, highly criticised for allowing harassment on it’s platform, has also announced that it will toughen its rules on online sexual harassment.

Both Facebook and Google have also promised to act against fake news by improving reporting tools, hiring more reviewers, and improving their algorithms.

Taking the legal route is another option.

The law provides redressal to victims under the Information Technology Act, 2000 and the Indian Penal Code (IPC). Some amendments were also added to the IPC after the Nirbhaya rape in 2012.

While it’s hard to come by granular data on these crimes, the latest National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) report this year shows 957 cases filed for publication or transmission of obscene or sexually explicit content.

This is the second largest category of cyber crimes, much higher than other categories such as cyber terrorism or banking fraud.

Another 157 cases have been filed under Section 66E which prohibits transmission of images of private area of any person without their permission.

NCRB also categorizes cybercrimes based on motives. In 2016, 686 cases were filed under the category of insult to modesty of women, while another 569 cases were filed for sexual exploitation.

Many cases of online harassment have also been filed under categories of causing disrepute (448), extortion (571), and revenge (1056).

Though these laws are comprehensive, very few victims have received relief.

NCRB data shows that only 12 people were convicted in 2016 for publication or transmission of obscene or sexually explicit content.

One reason is that you have to get a court order that directs websites to remove this content. This procedure is time-consuming.

Another reason is that the police don’t see cases through to the end. “In fact, many police officials show no interest in registering cases because they may not be aware what cyber crimes are all about and how to conduct inquiries in such cases,” says Halder.

She points that victims from smaller towns are apprehensive about approaching the police. Often, the police blame the victim. Or they release the accused after deleting the post and any related material from his phone. They assume that the accused won’t be able to retrieve this back, she says.

Cumbersome procedures make things further difficult.

If the server is located outside India, it is complicated to collect evidence. The Code of Criminal Procedure requires the Investigating Officer to write to a local magistrate. The magistrate, in turn, sends the request to the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI).

The CBI scrutinizes the application. Nagarathna says the CBI rejects a lot of cases at the vetting stage. “Unless they feel it is a very sensitive and serious case, they won’t forward the request,” she says.

Once vetted, a copy is marked to the ministries of External Affairs and Home Affairs. The Ministries then forward it to the diplomats of the country where the server is located.

Once the request reaches the host country, it has to be processed through a similar stack in reverse: justice department, a local magistrate, local police, and then the company that hosts the server.

“The entire process takes months, sometimes six months, and sometimes a year,” says Nagarathna.

She says that cybercrime investigations follow procedures designed for conventional crimes like murder. “Here, you have a crime committed in seconds. But, you’re still following a procedure which is so time-consuming,” she says.

Photo: Shamsheer Yousaf

Out in Elampillai village on the outskirts of Salem, Tamil Nadu, all these issues tragically came to a head last year.

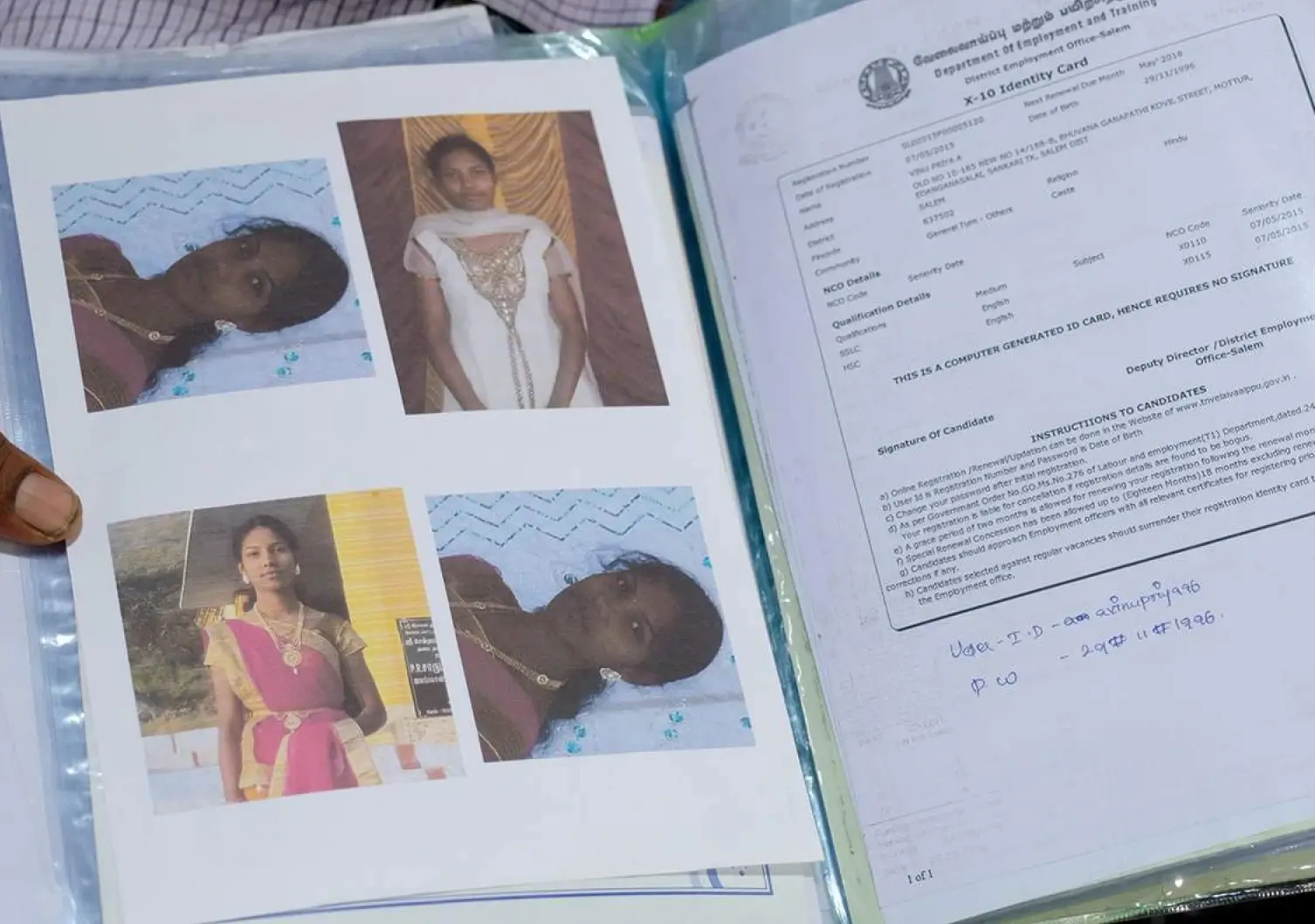

Manjula Annadurai gets no sleep these days, often crying through the night, while her husband Annadurai is often lost in his thoughts. Their only daughter, Vinupriya, hanged herself on June 27 last year. She was 20.

The story of Vinupriya’s suicide begins on the night of June 22 in 2016. Annadurai received a call from his nephew, Sathish Kumar, to ask if Vinupriya had a Facebook profile. Vinupriya said she did not.

Sathish came to his house and showed them a Facebook profile in Vinupriya’s name. It featured a photo of her in a bikini.

“It was a morphed photo,” explains Annadurai. “I was using Vinupriya’s photo as my WhatsApp profile picture. Somebody took that photo and morphed her face onto a photo of a scantily clad woman.”

The Facebook page also mentioned a phone number. It was the same number that Annadurai used for WhatsApp.

“We started getting calls late into the night. We were really terrified,” says Manjula. There were calls from Kerala, Mumbai, Hyderabad; from everywhere, she adds.

“We didn’t sleep for five nights. The impact was visible on my daughter. She started shrivelling up,” says Manjula.

To Annadurai, the sight of his daughter crying was too much to bear. Vinupriya was very close to him. The couple made a modest living weaving sarees, but they sent Vinupriya to an English medium school. They talk with pride on their daughter’s proficiency in English.

After completing her BSc in Chemistry, Vinupriya stayed at home for a year. But, her mother believed that a graduate like her should be working. So she got a job as a teacher at a school nearby.

She had plans for the future: Master’s degree, marriage, and life in a big city.

Annadurai liked to pamper Vinupriya. When she wanted a saree for a family function, Annadurai took her to Salem for saree shopping. It took two days for her to find the

perfect pink half saree.

The saree cost Rs 5,000, outside Annadurai’s budget. But he bought it, he says, because she had set her heart on it. Annadurai still keeps photos of her in that saree closeby.

When the morphed photos surfaced last year, Annadurai wanted to get the post taken down immediately.

He visited the Superintendent of Police (SP) at Salem the next day. He referred him to the Deputy SP’s office in the adjacent town of Sankari.

The DSP, in turn, sent him to the local police station at Magudanchavadi. Over there, the local inspector asked him to approach the cyber crime police station in Salem — right next to the SP’s office where Annadurai had started off.

At the cybercrime station, the officer told him taking down the profile would take 15-20 days. They claimed that the server was in Ireland. They also asked for a mobile phone in bribe so that they could communicate with Facebook. “They said without the mobile phone, blocking the profile would take another 20 days,” Annadurai recalls.

Photo: Shamsheer Yousaf

Annadurai says he met a police officer at a phone shop opposite the bus station in Salem. They bought a GSM sim card based mobile phone for which Annadurai paid Rs 2,000 and the cop Rs 300.

Meanwhile, the local police at Magundanchavadi wanted to question Vinupriya. They asked her and Manjula to meet them next to a school.

Sitting in their car, the sub-inspector asked if Vinupriya had given her photo to anybody. She said she hadn’t.

“The Sub Inspector shouted ‘You have given your photo to somebody. Tell me the truth’,” says Manjula. They didn’t believe Vinupriya.

“He yelled ‘If you make me get down the car, I’ll knock out your teeth’,” adds Manjula.

“His way of questioning was humiliating and torturous. And my daughter took it all to her heart,” Annadurai says.

Meanwhile, the late night calls continued.

On June 27, Manjula and Annadurai went to Magudanchavadi police station. They asked about the investigation but did not get a satisfactory reply. So they set out for the DSP office at Sankari, 25 km from their village.

On their way there, they received a call from a neighbour. He said Vinupriya wasn’t answering the door. They immediately turned around for home but soon received another call him.

Vinupriya was being rushed to the General Hospital in Salem. By the time they got there, she had been declared dead. She had hanged herself.

A suicide note was found beside her.

“What is the point of living after my life is finished,” she wrote. She asked for everyone’s forgiveness. That she had not made any mistake.

“Believe me. One second Sorry.. Sorry.. (sic),” she ended the note in English.

Manjula and Annadurai refused to accept their daughter’s body or let the hospital conduct a post-mortem until the police caught the culprit. They protested in front of the hospital.

The police sprung into action. They got the Facebook page pulled down the same day. They received the IP address from Facebook the next day.

A day later, they arrested Suresh, a textile worker from a village 2 km from Vinupriya’s house. They charged him for uploading obscene content and abetment to suicide. The cop who had asked for a bribe was suspended.

The family accepted her body after the accused was arrested. He was released on bail soon after.

“I lost my Vinupriya. There might be another Vinupriya, or a Mythili or any other girl elsewhere. Somebody can do this to them, right,” asks Annadurai.

Photo: Shamsheer Yousaf

This is why he wants the culprit to be punished severely. “Soon,” he says, clutching at a picture of Vinupriya in her pink half saree.

He burnt the dress in Vinupriya’s pyre. “It was her favourite dress. She loved it so much that I couldn’t bear to see it after she died,” he says.

Manjula starts to cry inconsolably.

The 2015 judgement in Shreya Singhal v. Union of India has changed the landscape on dealing with online harassment.

This judgement dealt with orders to block and remove online content. The Supreme Court struck down Section 66A of the IT Act, 2000 that censored online speech.

The Court ruled that it did not qualify as a reasonable restriction on freedom of expression. It also found its implementation excessive and vague. The abuse of Section 66A is well documented. The police arrested two girls from Mumbai in 2012 for a post on Bal Thackeray’s funeral.

The scrapping of Section 66A is seen as a victory for free speech. But the judgement also made it difficult to get offensive content removed.

How the Law changes facebook’s actions

Number of pieces of content restricted by Facebook in India over the years

| Period | No. of pieces restricted |

|---|---|

| Jan 2013 – Dec 2013 | 4,765 |

| Jan 2014 – Jun 2014 | 4,960 |

| Jul 2014 – Dec 2014 | 5,832 |

| Jan 2015 – Jun 2015 | 15,155 |

| Jul 2015 – Dec 2015* | 14,971 |

| Jan 2016 – Jun 2016* | 2,034 |

| Jul 2016 – Dec 2016 | 719 |

*For these time periods Facebook noted that following the decision of the Supreme Court, they “ceased acting upon legal requests to remove access to content unless unless received by way of a binding court order and/or a notification by authorized agency”.

Earlier, under Section 79A, intermediaries had to take down offensive content within 36 hours of notice once notified by an affected individual.

But the Shreya Singhal judgement shielded intermediaries from this liability. Now, they are compelled to remove content only after either a court order or a government order asks to take the content down. Requests from individuals have no legal force.

Since, this judgement there has been a significant drop in blocking content.

As per Facebook’s government requests report, the website restricted access to 15,155 pieces of content in January-June 2015 and 14,971 pieces in July-December 2015.

NCRB Cyber Crimes

Cyber Crimes registered in 2016 Under sections of IT act

| Section | No. of cases |

|---|---|

| Tampering computer source documents | 78 |

| Damage to computer/computer system | 3,321 |

| Receiving stolen computer resource or communication device | 196 |

| Identity theft | 1,545 |

| Cheating by personation by using computer resource | 1,597 |

| violation of privacy | 159 |

| cyber terrorism | 12 |

| publishing or transmitting of material containing sexually explicit act | 930 |

| publishing or transmitting of material depicting children in sexually explicit act | 17 |

| Retention of information by intermediaries | 10 |

| breach of confidentiality/privacy | 35 |

| other cyber crimes | 713 |

| TOTAL | 8,613 |

Following the judgement, during January-June 2016, this number dropped to 2,034. It fell even further to 719 during July-December 2016. In a note below the report, Facebook attributed this decline to the Supreme Court judgement.

Unlike Vinupriya, Subudhi received great support from the police from the beginning. Until the politicians began meddling in the case.

Besides Subudhi, FactorDaily has spoken to Chadha, Subhidi’s mentor and child rights activist, who corroborated the account. FactorDaily has also reviewed emails and SMS messages which Subudhi sent regularly to update Satyabrath Bhoi, DCP of Bhubaneshwar.

The day after she filed the FIR, Subudhi was travelling to Puri, when she got a call from a party colleague. He wanted to meet her urgently. “I told him if it’s about the case, I’m not interested. But he pleaded with me, so I went to his office,” she recalls.

Once she reached there, he handed over his phone to Subudhi. It was a call from a former minister from her party. Subudhi says he began talking about a nephew of his. That he is a relative, but they do not keep in touch anymore.

Initially, Subudhi was confused by his talk.

“He said that if you take any action, or if anything is proved, or any case is going on, let him get punishment and penalty,” she says.

Subudhi asked him who was he talking about.

“Suryanarayan,” he told her.

At this point, she says, she realised that he was referring to the Surya that the DCP had shown a picture of.

“By then, I was sure Surya was involved in my case. I felt that they were trying to convince me that I shouldn’t speak up if something comes up during the inquiry. I told him that I was unwilling to compromise,” she says.

Odia media has widely reported that the Surya is the nephew of Sanjay Das Burma, a former Minister of State in the government. Subudhi also named him in a press conference she held on June 3. Burma has not responded to a request for comment from FactorDaily at the time of publishing.

The colleague who had invited her for the discussion, suggested it was an in-party matter. He advised her to be careful and speak cautiously, she says. “I told him I was not accusing anybody and left his house,” she adds.

The pressure on Subudhi to drop the case continued. On the way to Puri, she received a series of calls from several party workers. An ex Zilla Panchayat member from Puri called her and said that Surya was innocent. Another girl called the next day, claiming to be Surya’s sister. She said that her name was in the post and that her brother was not involved.

Subudhi sent an SMS to the DCP with the phone numbers and the corresponding names as per Truecaller. She added: “Calling me since yesterday to tk bk withdraw case — Linkan Subudhi.”

With the calls persisting, Subudhi complained about the political pressure to State Women’s Commission on June 2. Later in the day, she met Chief Minister Naveen Patnaik.

Subudhi has had access to him ever since she came back to Odisha after the Noida attack.

But, an incident before the meeting underlined the pressure she was facing. A government official took her aside and tried to convince her not to discuss the issue with the CM. “He told me ‘This is an internal party matter. Keep calm. Keep quiet. We’ll solve it.’,” she says.

Subudhi stood her ground. “I replied ‘Today this will happen. And, tomorrow, you’ll ask me to sleep with somebody saying it’s an internal party matter and ask me to keep silent. To keep it within the party’,” she says.

Soon, Patnaik came out and met her. “The CM was friendly and sympathetic. He said he had spoken to the police and they were taking action. ‘Very soon you’ll get a response’,” she says. Odia media widely reported the meeting.

During the meeting, she missed a few calls from the DCP. When she called back, the DCP said they had nabbed the culprit. “I asked him if I could meet him. He said yes,” she recounts. Subudhi left for the Commissioner’s office with Chadha.

The first thing that struck Subudhi odd was that this was not the same person whose photo the DCP had shown her. This was not Surya, but Mithun Sahoo.

“Do you know me,” asked Chadha, who is well known across Odisha as a social activist.

Sahoo, shivering in the air-conditioned conference room, replied yes. That he had seen her on TV on several occasions.

“Then, do you know her,” Chadha asked, pointing to Subudhi.

“No, I don’t know,” he replied.

Chadha began asking elementary questions to Sahoo to catch him in a lie. As the questioning went on, he started to contradict earlier answers.

“First, he says he knows nothing about this case. Then, on the police officials’ cue, he says, ‘Yes I have confessed,’” says Subudhi.

A clue to Sahoo’s relationship with the former minister came out when Chadha asked him which party his family votes for. In the flow of conversation, Sahoo replied that he voted for the former minister.

After this conversation, Chadha said this was not the culprit and walked out of the room.

Photo: Sriram Vittalamurthy

Subudhi stayed back to get more information. She asked him how he got her picture. He was unable to answer. “An officer in the room prodded him ‘Did you get it from the net? Did you get it from Google Search’,” Subudhi recalls.

He replied yes.

“Whatever they were feeding at that point, giving clues to him, he was answering that,” says Subudhi.

Subudhi asked what search term he’d used to find her picture. “Did you search for ‘Odia girl’ or anything like that,” she asked him. He said yes.

Subudhi handed over her phone to him and asked him to find her picture using Google search. “He looked at the officer, then he looked at the phone. He looked at the officer again. He typed something, but couldn’t find anything,” says Subudhi.

The police officials continued to offer cues. “Did you search for Odia girl, Odia sexy girl, Odia women, Odia popular girl,” she recalls one of the officers prodding him. He still couldn’t find Subudhi’s photo.

Subudhi got up to leave. “I told the DCP, ‘Sir, this is not the guy,’” she says. She also told the Commissioner that he was not the culprit.

A day after she met Sahoo, she said at a press conference in Bhubaneswar that the police had arrested the wrong person. Following her press conference, local activists staged protests and demanded arrest of former minister Sanjay Das Burma.

Subudhi is familiar with computers and website technologies from her job as an IT consultant. Before meeting Sahoo, she had asked the Commissioner what evidence they had.

The DCP showed her the user id, password, and the cache history of the browser on the phone. Subudhi asked them if they got the database server logs from the website. Subudhi says the police agreed to email the details to her.

After the meeting with Sahoo, she asked for the details. The Commissioner said that he would mail them to her immediately. “ But he did not,” says Subudhi.

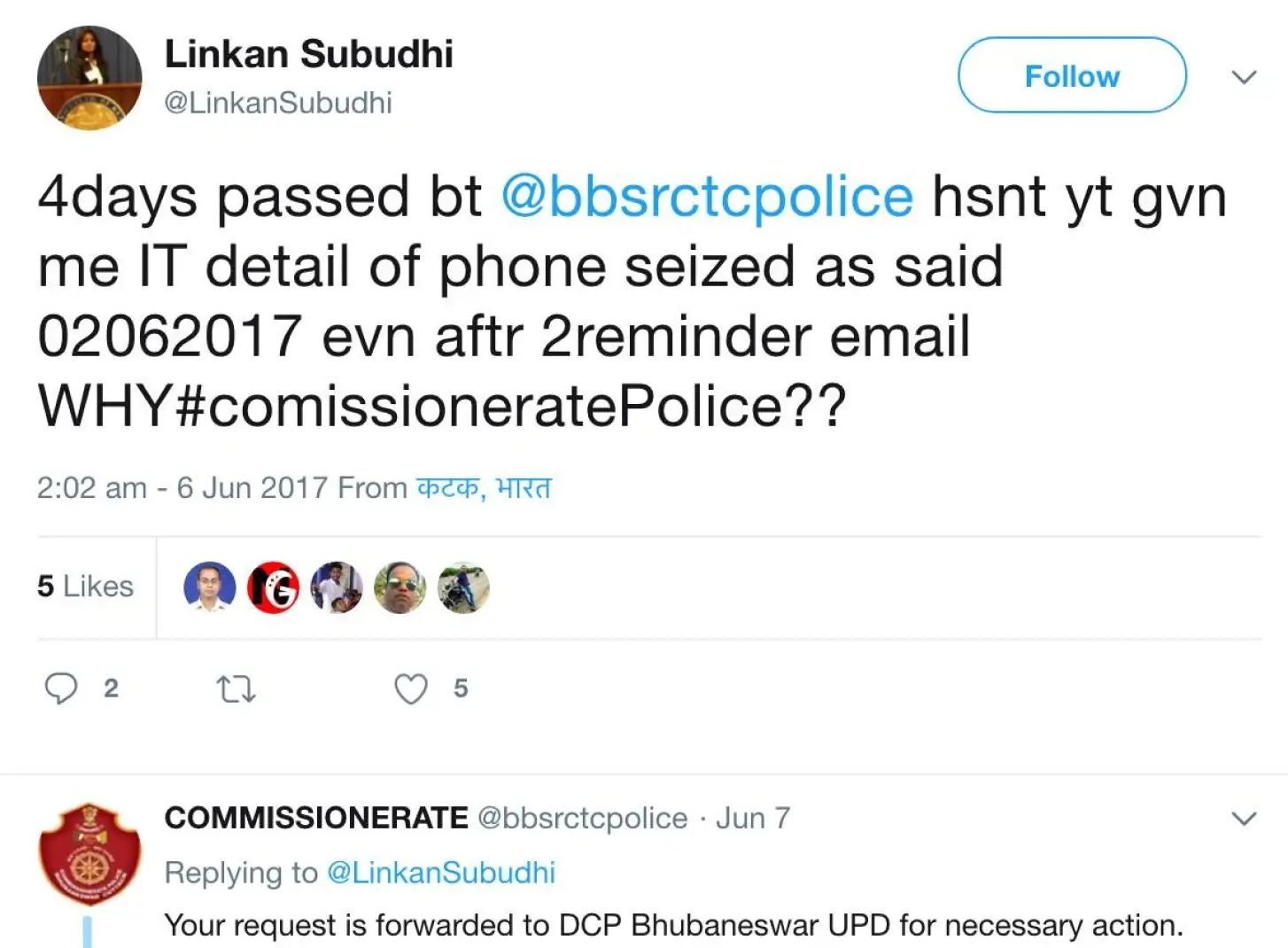

A few days after there was no response from the police, Subudhi tweeted to the Commissioner.

The local police station in-charge called her the next day. Subudhi says they just wanted to convince her that they got the right man. They told her that they hadn’t collected server details.

By the end of the interaction, the officer told her that she was asking too many questions. “He told me that he had another case,” says Subudhi. “He then folded his hands and said ‘Namaste’ as a cue for me to leave.” Further emails to the Commissioner yielded no response.

Fighting against a powerful former minister in her party has had a toll on Subudhi’s political career. Her party members began shunning her.

A fellow party member met her after the press conference at her house and asked her: “‘Why did you name the minister? Come with me, and we will go and talk to him. Just say you’re sorry’,” Subudhi recounts. “Why should I be sorry,” she replied to the person.

Today, the party has completely outcast her, she alleges. “They used to call and ask me to come to every party meeting. They have stopped inviting me. Now they’ve outcast me because they think I’m wrong,” she says.

“They want a compromise. A silent compromise,” Subudhi says.

She hasn’t given up hope yet. Sahoo was out on bail on June 29 as the police had not submitted a report. She’s filed an appeal in the High Court, but her case is yet to be heard.

Though her political career has come to a standstill and there has been no progress on her case, Subudhi sees some change. “In Odisha, more women are now coming forward to complain and file FIRs in similar cases,” she says.

“That’s progress”.

(with inputs from Monica Jha)