Illustrations by Somesh Kumar

Photographs by

Pankaj Mishra

Saba Khan was five years old when she first began borrowing comic books from a neighborhood kirana shop in Bagh Dilkusha, on the outskirts of Bhopal. She would thumb through Chacha Chaudhary and Natraj comics for one rupee an hour, racing against time to finish them before returning the worn-out copies.

“I would finish them in a few minutes!” she recalls with the same excitement she felt as a child.

But even then, a question gnawed at her—why should anyone pay to read?

It was a question that lingered, even as Saba’s life unraveled around her. An accident involving her parents pulled her out of school time and again. The dream of a steady education seemed as fragile as the pages of the comics she devoured.

Yet, something inside her never wavered.

A Library Takes Root

By the time she clawed her way to the eighth standard, Saba, a girl taunted for teaching others while she dropped out, had started her first library in Bagh Farahat Afza. It was a modest setup where children from the community would gather to read.

“Khud school nahi jaati aur doosron ko padhati hai,” the neighborhood gossiped.

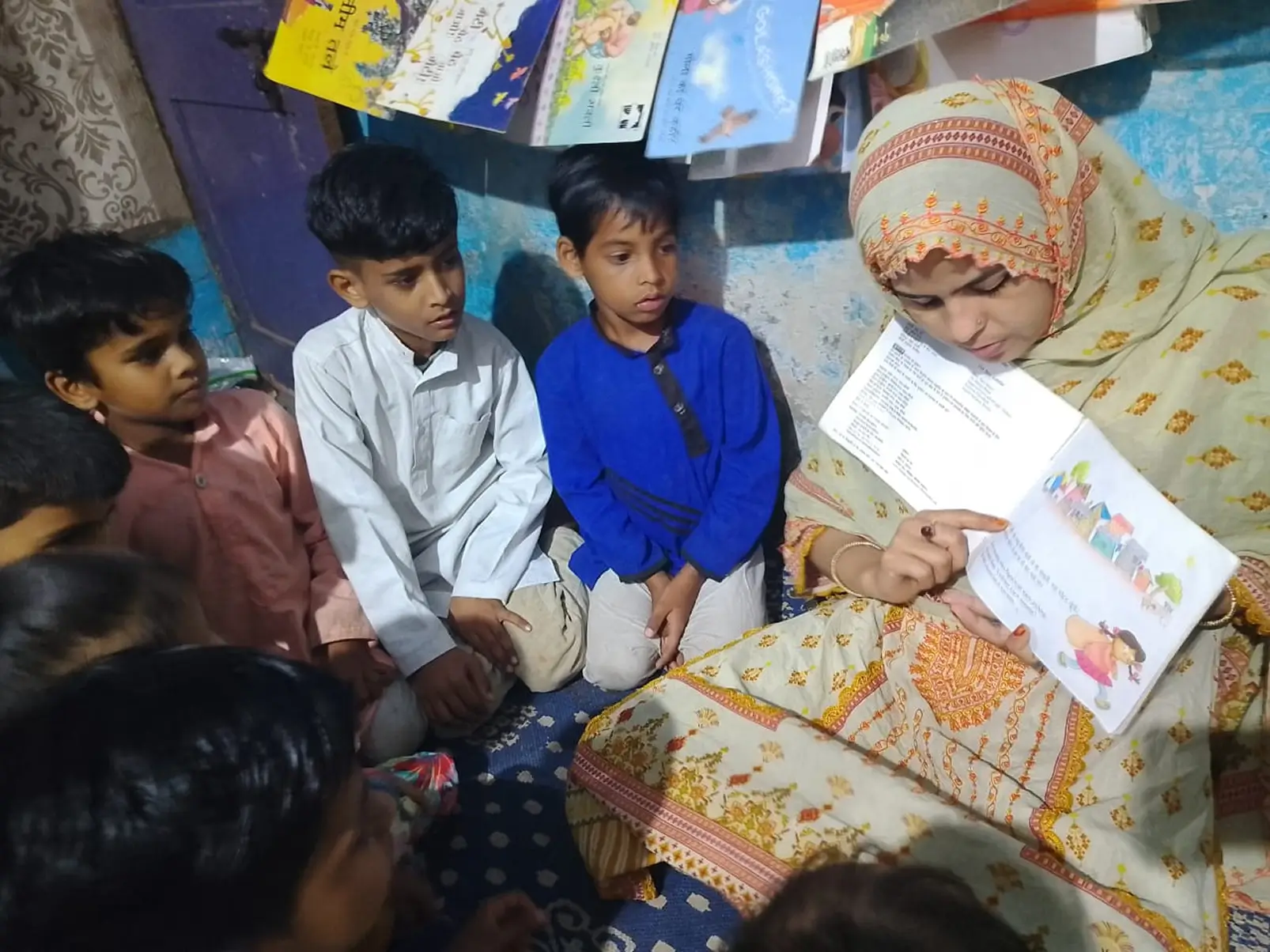

She wasn’t fazed. Every evening, that library—nothing more than a small, dimly lit room—came alive with young readers eager to escape into a world of stories.

In October 2024, I walked with Saba into the lanes of Bhopal’s Gandi Basti, also known as PC Nagar.

It was like stepping into a hidden pocket of Bhopal. The lanes were narrow but clean, lined with modest homes. Each lane twisted into different paths, leading to families living quiet, close-knit lives. The ground was soil, and trees offered shade where they could.

With its tin roof, the makeshift library stood out against the modest surroundings. I wondered how it must feel inside during Bhopal’s scorching summer. The walls were alive with color—handmade newsletters and posters crafted by the children who visited regularly. Each poster spoke of the library’s impact, from quotes about books to childlike drawings of imagined worlds.

Zoya, now 23, started coming to the library as a curious 11-year-old. She now manages the PC Nagar library.

Saba’s work has now expanded to a dozen libraries around Bhopal. Communities offered her spaces to run them, no questions asked. “On rainy days, families ensure the books stay dry, even if the rest of their house gets wet,” Saba told me.

This year, out of 56 applicants, 22 girls will head to college through the Savitri Bai-Fatima Shaikh fellowships offered by Saba’s network of libraries.

Librarians like Saba Khan are turning books into agents of change. They promote literacy and challenge societal norms through simple read-aloud sessions, from caste discrimination to gender roles. With support from programs like the Adhyayan Foundation’s Read-Aloud initiative, these librarians are transforming libraries into hubs of learning, activism, and community.

Books on the Doorstep

During the COVID-19 pandemic, when schools all over India were closed, the importance of libraries grew even more. Nita Luthria Row, executive director of the Adhyayan Foundation, recalls starting a Read-Aloud program in Goa to help children continue learning in a time of uncertainty.

“We wanted children to develop a positive relationship with books and reading,” Nita said. “The read-aloud creates a warm, caring environment, especially for children from lower socio-economic backgrounds who tend not to have much exposure to books beyond textbooks.”

A tweet about this program caught the attention of Uma Mahadevan-Dasgupta, Additional Chief Secretary, Panchayat Raj, in Karnataka. Inspired, she invited Adhyayan to pilot the program in Gram Panchayat libraries across two districts.

Nita remembers how library supervisors in rural Karnataka embraced this shift. “It was a bold experiment, and its results surprised everyone, including us,” she shared. Supervisors who had once been unnoticed began hosting weekend read-aloud sessions that attracted children to their libraries in numbers they had never seen before. “Children would knock on their doors even on days the library was closed, pleading for it to open.”

When the world shut down during the pandemic in Bhopal, Saba and her team took to the streets, delivering books door-to-door. It started small to keep the children reading, but soon, parents and other family members began picking up the books.

In Bhopal’s Mother India Colony, a 14-year-old girl named Muskan, who had never been to school, asked for books. When Saba returned to her neighborhood two days later, the young girl asked for a sanitary pad. The library, it turned out, had become a place for many needs.

As Saba’s libraries expanded, so did their impact. Zoya, who first came to the library as an 11-year-old in 2012, runs her own community library. Zoya’s elder sister is in college, which is a small but significant shift in the community.

The Right to Read

In a place where girls are often married young, Saba’s libraries offered a different path: toward education. The impact was felt in the growing number of readers and how families began thinking about their daughters’ futures.

Saba recalled a time when girls from the Mehtar community were denied admission to a local school because of their caste. The teachers dismissed the girls as unworthy of education. “Their homes are so dirty,” the teachers at nearby Kasturba School scoffed.

With Saba and the educators’ support, the girls returned to school the next day, demanding their right to study. The library had become more than just a place to read—it had become a place for fighting back against injustice.

Saba doesn’t just build libraries; she grooms the young librarians who run them, teaching them how to nurture a community of readers. “The kids borrow books, go home, and start their own mini-libraries,” she said, smiling. “Sometimes they even get adults involved with read-aloud sessions.”

Saba Khan is not alone in her quiet revolution. Across India, librarians like her are transforming the act of reading into something radical, something cool. From the remote hills of Uttarakhand to the towns of Maharashtra and the rural corners of Karnataka, these librarians—many of them women—are reimagining what it means to hold a book, share knowledge, and bring communities together through the power of stories.

A Network of Change

In Kalyan, Maharashtra, Sajitha S.K. has been using her library as a tool for societal change. Last year, she held a read-aloud session of मेरा नाम गुलाब है (My Name is Gulab), a story about a young girl confronting the injustice of her father’s work as a manual scavenger. The book by Sagar Kolvankar resonated deeply with the children, sparking a discussion on the dignity of labor.

“The children realized the unfairness of the stigma attached to Gulab’s family,” Sajitha shared. “They began to see that change is possible, and they could be part of it.”

After reading My Name is Gulab, children in her community began practicing waste segregation and even role-playing tasks once seen as “shameful.”

Small Victories in Kodagu’s Libraries

Working across rural libraries in Kodagu, Varsha Vijaya Kumar, Project Manager for the Karnataka Read-Aloud Program at Adhyayan, faces a complex landscape of challenges. Resistance to change is common—libraries often lack basic amenities like toilets, and in some areas, girls aren’t sent to school or libraries at all.

Child marriages and poverty compound the struggle, making it difficult to convince families of the importance of reading and learning. “There are days when I lose hope,” Varsha admits. “But then, I erase it all from my memory and start fresh the next day.”

Despite these hurdles, there are moments of breakthrough, as seen in the stories of librarians like Damyanti and Yashoda. In Kundacheri, Damyanti describes the children as birds: “They come to the library like birds, find what they’re looking for—be it books, games, or friends—and fly away.” Inspired by a training session on nature by the Nature Conservation Foundation, her analogy captures the freedom and curiosity that the library now represents for these children.

This grassroots effort has expanded through programs like Oduva Belaku in Karnataka. Spurred by a tweet, Uma Mahadevan-Dasgupta, Additional Chief Secretary of Rural Development, launched a read-aloud initiative across 6,000 gram panchayat libraries. The program, supported by Adhyayan Foundation and Bachpan Manao, trains library supervisors to lead read-aloud sessions, shifting their role from bookkeepers to community leaders.

It’s already transforming districts like Chikkamaguluru, Tumakuru, Belagavi, and Kolar, where libraries once seen as quiet corners are now vibrant learning centers, sparking curiosity and engagement among children.

In Gaalibedu, Yashoda has witnessed a shift in the library’s atmosphere since receiving training. “Before, the children would just linger around,” she recalls. “But now we have conversations. They ask questions, and we find answers together. I feel like I know how to engage with them.” This newfound connection between librarian and child has transformed the library from a passive space into a dynamic center of learning and dialogue.

When the Read-Aloud program first reached rural Kodagu, children were hesitant. “They told me they preferred reading by themselves,” Nita Luthria recalled. But once the sessions began, their attitudes shifted. The simple act of being read unlocked a new joy, and the children began to eagerly look forward to these sessions.

One story that stands out is that of Philomina, a teenage girl with a physical disability, frustrated by her circumstances and disconnected from her studies. Her mother, who had struggled to manage her temper, confided in Padmavathi, the gram panchayat librarian of Nerugalale in Karnataka’s Kodagu district.

Padmavathi began visiting the girl weekly, reading aloud to her in the comfort of her home. Slowly, these sessions became the highlight of the girl’s week. “Her mother said the girl had become more amenable and happy thanks to those visits,” Nita shared.

Reading aloud is quietly becoming a social movement, shaping not just the children but also the librarians—often overlooked figures in India’s everyday life. Once unnoticed, they are now treated with respect and greeted warmly in their villages. “Children knock on their doors even when the library is closed,” Nita Luthria shares. Women now gather at the libraries for skill-sharing sessions, and librarians are invited as guests of honor at village functions.

A Mother’s Legacy

As Saba looks back, her thoughts often turn to her mother, who passed away a month ago. Growing up, she felt ashamed that her parents fought for laborers instead of having “normal” jobs. “Now I understand why they did it, and I’m ashamed for ever feeling that way,” she admits.

Her mother didn’t fully grasp what NGOs were, but she proudly told others, “Meri beti bachchiyon ko kitaabon ke zariye taleem se jodne ka kaam karti hai”—she helps connect girls to education through books. Saba’s mother, who learned to read later in life, loved books.

“Ammi’s passion for reading lives on through the libraries I run,” Saba reflects. Like her parents, Saba continues the fight—this time, through the power of books, opening new worlds for girls just like she once was.

A shorter version of this story first appeared in The Times of India. You can read it here.