Six days before he died of pancreatic cancer, Arvindkumar Alagarswamy knew his time was coming. “I fear I am going to die,” he told Lakshmi, his wife of 13 years. It was nearly midnight on April 13 and Lakshmi pleaded Arvind not to give up.

Arvind, 36, just laid back, his frail frame sinking deeper into his hospital bed. He looked like he was giving up.

From the time doctors at Global Hospital in Chennai had diagnosed him of inoperable, late-stage pancreatic cancer three months earlier, Arvind knew it was always going to be a one-sided battle. Pancreatic cancer is mostly fatal. It is mostly detected after cancer cells have spread beyond control and the survival is rare — less than two per cent of those diagnosed live more than five years. Even Steve Jobs, his role model had succumbed to pancreatic cancer in 2011.

But for Lakshmi, 35, Arvind giving up was just not him. “He always figured a way out, no matter what,” she says. “He would decide the next and work towards it undyingly.”

That doggedness along with sheer hard work, smarts and salesmanship had made Arvind the CEO of a firecracker among Indian health technology startups. Over six years, Arvind had co-founded, built up and steered Attune Technologies through several near-death experiences. He raised over $16 million from investors including Norwest Venture Partners, Qualcomm Ventures and Mercatus — valuing Attune at nearly $60 million. Attune’s cloud-based software solutions helps small to medium-sized hospitals automate and integrate operations on a single platform. The software powers functions of billing, lab management, patient records and finance for hospital customers such as Medall in Chennai and Dermpath Consult in Dubai.

With nearly $10 million in revenues, Arvind’s goal was to take Attune’s top line to $100 million in the next three to four years.

For Attune, Arvind’s death in the early hours of April 20 “was like losing the only engine of a plane in flight,” says Mohan Kumar, Norwest’s executive director in India. Kumar, a former head of Motorola’s India engineering centre, didn’t have a playbook to refer to when the news first came in.

In many ways, Arvind was the quintessential Indian tech entrepreneur — a Madras University electronics and communications engineering grad, a software systems postgrad from BITS Pilani, a few years spent in software jobs, a management diploma from IIM-Calcutta, and then, bitten by the startup bug.

When I first heard of Arvind’s death and about the crisis Attune was facing, I realised it’s an important story to tell for many existing and wannabe entrepreneurs looking to build their startups. Admittedly, it piqued my interest even further when Lakshmi told me that my number and email were on Arvind’s phone! I don’t recollect meeting him but it could well be that he wanted to pitch his Attune story to a journalist. I will never know.

The life of a startup and its founder(s) gets mostly captured through stories of funding, management changes, mergers and acquisitions, and so on. What gets lost is the human aspect of entrepreneurship involving the families who sacrifice their time and emotions, friends and colleagues. And, the founders’ own real dreams, bordering on the ethereal, about making a dent in the universe.

FAMILY MAN — ALSO, AN ENTREPRENEUR

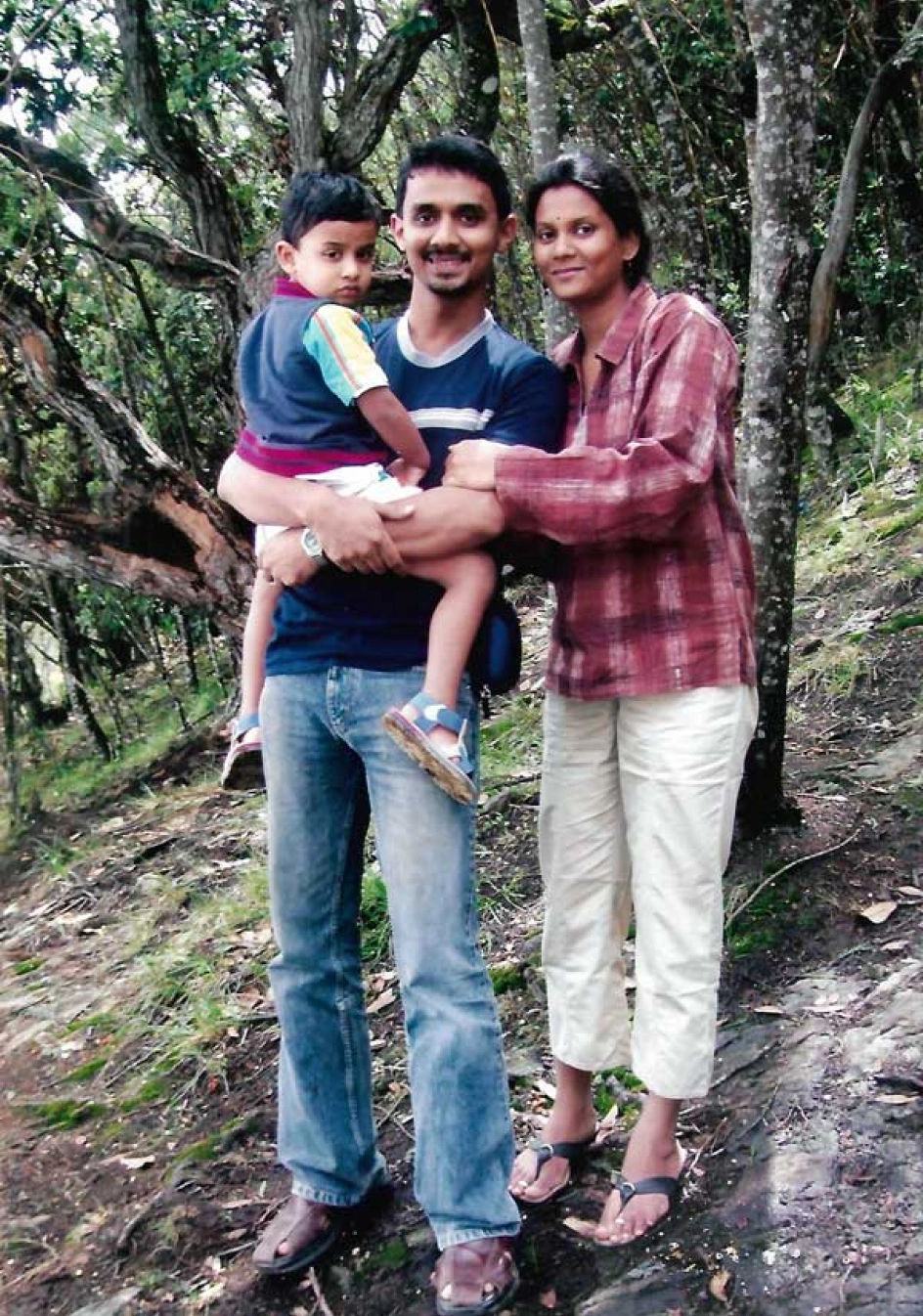

Lakshmi — her full name is Santhanalakshmi Arvind — can’t stop talking about Arvind. She’s at times breathless while recollecting their lovebird days in college, at times wistful when she points to pictures of Arvind on the bedroom wall, and smilingly complains about how she was the wife number three after his first two loves: cricket and entrepreneurship.

The mother of two boys has been a software engineer for well over a decade with stints at Satyam Computer Services and Accenture. She now works as lead project manager with iNautix, a technology captive centre in Chennai of BNY Mellon Bank in the US.

We are meeting at Arvind’s three-bedroom apartment in Thiruvanmiyur, a residential pocket in south Chennai famous for its temples and large campuses of technology companies. A. Krish Vikram, seven years old, keeps lurking around during the interview, feeling restless and perhaps jealous of the time Lakshmi is spending with me. Her elder son, A. Vidwath Paraakram, 12, is composed and keeps calling Krish out to ensure we have a conversation free from distractions.

Arvind and Lakshmi didn’t disagree on how to name their kids. “Arvind gave the first names to our sons, while I picked their second names,” she says. The boys are coping with the loss of their father in their own ways, she says, but are mostly holding back their emotions. Krish wrote a few lines how he’s missing his father in his school notebook some days ago; the teacher showed Lakshmi the notebook.

Arvind, she adds, wanted to learn carnatic music with Vidwath. “The younger one is mad about cricket, just like his father.”

She opens Arvind’s laptop, and pulls up some files for me. They are startup ideas that her husband carefully documented — from a laundry business to a platform for finding paying guest accommodation in Chennai and another one about an indoor badminton club. Details of target audience, the demographics, finances, business plan, all sorted out.

HEY, JUNIOR!

The first time Lakshmi saw Arvind was when he was ragging juniors at Chennai’s Jerusalem College of Engineering.

“I was really scared when he asked me to sing a song at the bus stop, in front of everyone.”

Lakshmi was a year junior to Arvind in the college and did computer science.

“I said I couldn’t do it.”

Surprisingly, at least for her batchmates, Arvind let her go.

And that’s how she fell for him.

“Secretly, I started liking him.”

They got married in Chennai on June 11, 2003 after Arvind convinced his Brahmin family that he would spend his life with Lakshmi who belonged to a different caste.

Back then, Arvind used to work at DSQ Software in Chennai. But three months after the wedding, he got a software architect’s job with Philips Software in Bangalore and relocated. Lakshmi joined him after a few months.

“Cricket made him popular everywhere,” recalls Lakshmi. At Philips, Arvind helped his team win an inter-company cricket tournament scoring 80 runs off 39 balls.

It was at Philips that Arvind started developing a passion for health care and technology and a desire to build a world-class product from India.

“He didn’t like the fact that India centre of multinational companies such as Philips weren’t allowed to build a product from scratch; he wanted to change that,” says Lakshmi.

When Arvind first shared with his parents his plans to quit the professional world in May 2008, his father, a retired company secretary, was concerned.

“We Brahmins are risk averse people. We have been conditioned to work on 9 to 5 jobs, save up cash and put anything extra in fixed deposits,” Smitha Alagarswamy, Arvind’s sister who now lives in Australia, tells me on the email. “Having grown up in a family like that, it was not just a leap for him but breaking the barrier.”

SAVING ATTUNE

“Oh my God!” Norwest’s Kumar, who calls Arvind “a dear friend”, whispered to himself when he entered the Attune office on the morning of April 21, the day after Arvind passed away.

Almost everything appeared broken to him, not because things were that bad, but more because almost everyone in Attune was aligned to functioning with a leadership style that didn’t exist. Attune’s rockstar founder was no more there to steer the startup.

“For an outsider, startups can look really chaotic if you suddenly jump inside them,”

– Kumar

arvind’s friend

When Kumar first heard about Arvind’s cancer in January he couldn’t tell if it would be fatal. A week before he passed away, Arvind even texted Kumar saying he would be back in June or July after another round of chemotherapy.

“Most of the changes we brought at the board level and across the company, were aimed at managing the crisis in the interim, until Arvind returned,” he says.

The board had planned for the short term, asking co-founder Ramki — that’s how Ramakrishnan Venkataraman is called by everyone around him — to take over sales apart from product functions. Kumar himself started spending more time with Attune’s customers and taking a hard look inside.

Couple of days before Arvind passed away, Kumar got a call from Chennai. It was Ramki on the line. Arvind’s doctors had given up and it was only a matter of time — another day at best. On April 19 night, Kumar decided to take an early flight the next day to Chennai.

Ramki called Kumar just when he was about to board his flight next morning. Arvind had died.

HOW T0 DISCOUNT A ‘IF I AM HIT BY A TRUCK’ SITUATION

- Delegate important tasks, develop a strong second line

- Do an informal stress test of your company and teams once a year

- Processes may seem bureaucratic but they are there for a reason. Embrace them and make sure your team does.

- Have a co-founder who can scale in terms of leadership when needed

- Must read; Chasing daylight; How my forthcoming death transformed my life by Eugene O’Kelly , former CEO, KPMG

- Work hard, play hard

It was clear that Attune was faced with something worse than its near-death experiences of the past. The death of a founder can be fatal for a startup, as Sascha O. Becker and Hans K. Hvide of University of Warwick and University of Bergen note in their May 2016 paper after researching hundreds of startup founders’ deaths.

Kumar puts Attune’s chances of survival at only 20 per cent at the time of Arvind’s death. The late CEO led important functions of sales and top customer engagements. “Even now, I would put it as 50:50.”

(Kumar clarifies while the above was an immediate reaction on Arvind’s death, he was talking about organisational dynamics and the company meeting its current year goals. The company had built a strong second line of leadership that was hired in the last 12 months. Raji Iyer was hired as head of marketing, Harish S as head of customer support, and Hari Ambrish as head of engineering and products. The new senior executive team takes time to settle and they did not have enough time with Arvind.)

With Arvind gone, quick fixes weren’t enough at the company.

Kumar spoke to other two investors of Attune — Karthee Madasamy of Qualcomm Ventures and Ravindran Govindan of Singapore-based Mercatus Capital, and told them that the turnaround plan will have to be executed carefully, but without shying away from some bold steps needed to put the startup back on the growth path.

Ramki was made the interim CEO and a townhall with the company’s some 200 employees was organised.

“What’s happened is unprecedented, we stand by the company and we must protect Arvind’s legacy, make this successful,” Kumar told everyone.

Acquire to survive

Then, Kumar started looking at different functions within the startup with forensic eyes. That followed some unpleasant discoveries about the startup’s prospects ahead.

First of all, it appeared that while Attune’s solutions were good, most hospitals weren’t ready to pay for it, the customers were haggling too much on the price.

“The (Indian) market didn’t seem to be ready,” says Kumar.

And because Arvind was almost like a single-man sales and marketing army, the function of customer engagement (and, even, finance) had started taking a toll in his absence over six months.

“If Arvind were around, he would sign up over a dozen new customers and all the problems would get dwarfed,” says Kumar.

The same problems can look insignificant from a founder’s point of view.

“Founders are optimistic and they believe in last minute miracles.”

– Kumar

arvind’s friend

But from an investor lens, the same situation could appear disastrous. “The plane needed new engines while still in the flight,” says Kumar.

Ramki proposed that Attune aggressively push for market expansion outside India.

The company started beefing up its sales teams for the markets of Middle East, Thailand, Sri Lanka and Indonesia.

And then, Kumar started on a plan that would appear excessively bold — even, downright risky — to many.

“Attune’s biggest challenge was that its products were operationally focused on making large hospitals and lab chains save costs by using cloud hosted software solutions. It takes time to close a deal and very price sensitive,” says Kumar.

But the hospitals overseas and some in the Indian market were looking to pay for solutions that would help them build new revenue. Cost savings were nice to offer but it wasn’t as compelling a proposition as boosting sales, Kumar realised.

So, in June, Attune acquired two startups for over $4 million, and added products that had existing footprints in new markets.

Kumar wouldn’t disclose the names of these startups. “The first company was added to get into “improving revenue side of providers” and the other was for market expansion into LatAm markets,” he says.

And, more than just the new market access, Attune now had two more entrepreneurs in leadership positions.

“We now have two more founders with similar domain expertise,” he says.

What about the risks of integrating two new startups at a time when Attune itself was in a turbulent phase of its journey? Kumar agrees it’s a risky move but says extraordinary situations require bold bets.

“Who will be the CEO?” asked executives of the two new startups who were joining Attune.

“Let’s forget that for now, and focus on how each of your products can help Attune become $100 million revenue company in three-four years,” Kumar told them.

The move seems to be working so far although it’s still too early to call it a home run. For instance, Attune has now Spanish language customers in Latin America after one of the acquired startups helped cross-sell the product in local language.

“We now have three new engines on the plane but they should be firing in sync otherwise the plane could crash,”

– Kumar

arvind’s friend

What about cash to fund growth? Attune’s existing investors are raising $2 million in an internal round to help with the crisis for now.

In about six to nine months, the company will hopefully have a permanent CEO and will have growth and stability to show to potential investors.

Arvind’s life

Amit Nigam and KSS Sudhakar, two of Arvind’s IIM-Calcutta batchmates, were busy discussing their startup CheckGaadi.com on April 21 morning in Bangalore when a Whatsapp alert of Arvind’s death stunned them.

“We just couldn’t believe it, we didn’t know anything,” says Nigam who first met Arvind in November 2007 when they started their post graduate program for executives at IIM-Calcutta. Since then, Nigam and Arvind were thick.

Two months before he died, Arvind wrote an introduction email for Nigam connecting him with online funding platform Letsventure’s Shanti Mohan for the funding help. He wrote it from the hospital bed but Nigam didn’t know how sick his friend was.

“I had no clue. I now look back and realise what he would be going through while writing that email,” says Nigam. Arvind and his family kept everything to themselves until the last day. Only a few in the family apart from the co-founders and investors of Attune were aware that the end was close.

The IIM batchmates picked a car and drove from Bengaluru to Chennai. By the time they reached, the funeral was over. Dumbfounded, both Nigam and Sudhakar walked to the nearby beach before going to Arvind’s home to commiserate with the family.

“When we reached his home, no one was crying; his father told us Arvind made them promise they won’t weep,”

– Amit nigam

arvind’s IIM-Calcutta batchmate

In the 2007 executive MBA batch at IIM-Calcutta, Arvind and Sudhakar were the only ones who opted for entrepreneurship after graduation, shunning corporate jobs. “We called the duo — OOPS,” says Nigam. OOPS is B-school lingo for those who sit out of the placement season.

Arvind, who had worked in the health care technology domain across different roles at Philips Software and iSOFT until November 2007, started thinking of a health care startup while at IIM.

“He would bring up health care technology in almost every discussion in the class, no matter how relevant it was or not,” says Sudhakar. “I was like ‘Who’s this guy?’”

“I was also out of “the Ivy League” he kept with fellow batch mates who went out to have beer occasionally,” he says.

They were close, still. Arvind asked Sudhakar to join the founding team sometime during mid 2008.

By November last week of 2008, Sudhakar relocated to Chennai along with his wife and one-an- half-year-old son to join the founding team of Attune. By then, other founding members including Ramki, Anand Gnanaraj and Mohanaraj Paramagurusamy were also on board. While Arvind met Ramki when they worked together at DSQ Software in Chennai, others were “the friends of friends.”

With the help of some seed capital from Mohanraj, an old friend and a Sri Lankan settled in London, Arvind managed initial expenses. Mohanraj has been a “guardian angel” for the family since Arvind passed away, Lakshmi tells me, as her younger son runs around in her Thiruvanmiyur apartment.

The first year was tough. Attune’s founding team struggled on many counts — funding, getting the product-market fit right, and sales were among top challenges.

“During those days, there were no salaries and it became really difficult for everyone,” says Lakshmi.

So bad, that Sudhakar was beginning to find it impossible to cope with the startup’s struggles. His ailing father, existing loans, and rising family expenses made life uncomfortable. “I was not able to ensure a decent life to my family, had to send my son to a really cheap kindergarten and the cultural differences with others in the team made it impossible to carry on,” says Sudhakar.

Finally, Sudhakar quit Attune and returned to Bangalore to join Wipro.

“While Arvind did ask me to stay on, he didn’t make extra efforts thinking it was the best thing for me to leave and make ends meet,” says Sudhakar.

Losing a cofounder so early and running a cash-starved startup were among the early challenges Arvind had to steer through.

The startup struggles continued till late 2009 when Attune received angel funding from Mercatus Capital, a Singapore-based fund focused on backing early-stage startups. Raising money for a fledgling startup is never easy, what makes it tougher is when it’s not fancied by funders like, say, an ecommerce startup would be. Around that time, enterprise software startups weren’t receiving much attention and funding.

By the time Arvind and Ramki met Mercatus’ Ravindran Govindan, the company had too little cash left, barely enough to survive another two months. After Mercatus agreed to invest, the money was still taking time to hit the bank account.

During those days, both Arvind and Ramki borrowed money from their sisters and friends and family to ensure they survived.

“He struggled to pay the salary of employees, and he used to be really stressed every month end. I believe the lowest point in his journey was when he had to borrow money from me,”

– Smitha

Arvind’s sister in Australia.

During times of struggle, when Arvind would hardly spend time with his wife and sons, Lakshmi would jokingly say she wanted a divorce.

“Don’t divorce me now, you won’t get any alimony because I am not earning a salary. Do it after we raise funding and make money,” Arvind would tell her.

The first big funding for Attune happened when Norwest led by Kumar, invested $6 million in December 2012.

“Arvind had the ability to close sales deals and raise money; this could not be replaced,” says Mohan. “We bet on Arvind, we bet on Attune.”

The big $10 million funding led by Qualcomm Ventures came just last year, in October.

Some of his early customers had an emotional connect with Arvind, not a dry, transactional relationship.

A. Velumani, the founder of Thyrocare Technologies, a fully automated diagnostics company that listed its shares earlier this year in April, was one of the early Attune customers and also was a Norwest investee company. That’s how Velumani and Arvind got introduced in 2011.

Velumani, who lost his wife Sumathi to pancreatic cancer this February, couldn’t believe when he first heard that Arvind was down with the same form of cancer. Just a few months ago, Arvind had come to invite him for an event where Attune was receiving an award from research firm Frost & Sullivan.

“He was the first man outside the family who came to know about it (Sumathi’s cancer) since I knew I could not make it to that event and I wanted him to know the true reason. I did not cry but his eyes were wet,” says Velumani.

“When I heard that he is also having the same problem, I felt too bad that God was merciless. My children did cry a lot that they lost their mother too early only till they heard that Arvind’s children had it still bad,” adds the Thyrocare founder.

When he went to meet Arvind weeks before he died, Velumani couldn’t believe what he saw: Arvind had lost nearly 30% of his body weight from a few months ago and looked to be fighting a lost battle with cancer.

“I only hope Arvind and my wife both are in heaven and they emotionally what both of them lost – in family, life and society too early,”

– Velumani

founder of Thyrocare Technologies

Land plot = Seed capital

With funding and growth, Arvind’s life became hectic and at times really draining on his health.

“One night he came home from a trip at 12 am, woke me up and i kept thinking it’s a hallucination,” says Lakshmi. “Then, at 3 am he woke me again and said he was going to Singapore.”

Lakshmi recollects another trip when Arvind came back from Tanzania and asked her to become an entrepreneur. “He pitched a really good idea about employee engagement platform I could work with a former Accenture colleague,” she says.

Arvind would travel over 20 days a month, hunting for hospital deals in markets as diverse as Indonesia, Thailand, Africa and the Middle East.

Ramki, who first met Arvind at DSQ Software when a cricket team was being selected, says the biggest life lesson for him has been the brief time entrepreneurs get to spend with family, friends or, even, themselves.

“I now spend more time with my family,” he says, wiping tears. I am meeting him at the Attune office at Guindy in south central Chennai.

I come back to Arvind’s home and find his parents waiting for me.

His father, Muthuswamy Alagarswamy, 67, and a company secretary greets me with empty and red eyes. His mother, Padmavathy Venkatesan, 60, looks like she will burst into tears anytime but holds back. I am uncomfortable and don’t know how to reach out to them.

“Nothing brings more pride to a mother than someone calling her son inspiring, intelligent,” she says in Tamil, which Swamy translates it for me.

Swamy remembers how until last year he and Arvind would ride around Chennai on a TVS motorcycle looking up property for investment. In fact, the seed capital for Arvind’s startup came from selling a plot for around Rs 20 lakh.

After finishing Class 12, Arvind told his father he wanted to pursue a career in cricket as an opening batsman. “I used the examples of engineers-turned cricketers (Anil) Kumble and (Javagal) Srinath to convince him to pursue engineering,” says Swamy.

Third stage cancer

The end began with what appeared to be a dull stomach pain that Arvind talked about in April last year. By June, it was sporadic but severe back pain.

“The pain made him weak, slowly. We never suspected it could be cancer,” Lakshmi says.

In December, the pain in his back got so bad on a flight back from London that Arvind knew he had to seek help. He had also rapidly lost weight; he weighed in at 72 kg, which made his 5’ 11” frame on the lean side. (He had reduced to 50 kg in his last days at hospital.)

He got himself admitted in Chennai’s Global Hospital on January 5. It took a fortnight before the doctors diagnosed the real problem: pancreatic cancer.

On the evening of January 20, a junior radiologist at the hospital looked through scans of Arvind that showed swollen lymph nodes in the body. By then, the lymph nodes had swollen at least 20-times their normal size, a sign that it was what doctors call “third stage” when the cancer spreads to lymph nodes and major blood vessels. The patient, Arvindkumar Alagarswamy, didn’t have much time.

January 23: Lakshmi waited till midnight for the doctor came into the room. Arvind was still awake, awaiting the verdict. “It’s pancreatic cancer, and it’s secondary,” hepatologist Dr Joy Varghese told the anxious couple.

“I was dumbfounded, everything around me blurred,” says Lakshmi.

The doctor met Lakshmi separately and told her Arvind was headed to a critical and advanced stage. She wept uncontrollably, she tells me.

Sometime in the second week of February, there’s a little ray of hope, at least on the face of it, but enough for the family to regain hopes of a miracle.

That was Arvind’s first week of chemotherapy when a massive dose of cell-destroying chemicals is injected to stop or slow the growth of cancer cells.

“He regained energy… stayed up long nights sending emails to his office, poured coffee for all…. We felt we would be fine soon,”

– Lakshmi

Arvind’s wife

In the middle of all this, Lakshmi had sent Arvind’s reports to Johns Hopkins University’s pancreatic research centre. “They clearly told us there’s no hope. ‘We’re sorry.’”

After the first chemo session, doctors advised Arvind be shifted to home. But within weeks, things started worsening and he had to be admitted again, this time in Apollo Hospital.

“It was the first time I found Arvind scared of things… pain,” she says.

THE MIRACLE THAT DIDN’T COME

In January, Arvind had told the doctors to tell him when he was sinking so that he could prepare.

“But when the time came, Arvind’s mom refused to let doc… do his job as she never wanted her son to be told he is going to die. We all believed God will somehow do the best… a miracle,” says Lakshmi. Arvind made it almost a ritual to visit the Anantha Padmanabha temple in Adyar every week.

On April 17, the Sunday before he passed away, Lakshmi asked if she could bring their sons to meet him.

“He signaled no, and I started wondering if he’s detaching from everything.”

The night before he died, Lakshmi offered him tender coconut water. No, he said. Then, tears started rolling down Arvind’s cheeks, as if he almost knew it was the last night.

Even while discussing Arvind’s last few days, Lakshmi shows unusual calm and poise. “He groomed us this way, to be independent, positive and cheerful.”

In the early hours of April 20, at 4.20 am, Arvind lost the battle for his life.

As I take my leave of Lakshmi and Arvind’s parents and walk down the apartment block’s parking lot, I see a new, metallic grey B Class Merc Arvind had bought just last September, his first luxury acquisition. He drove a Hyundai i10 before that.

“A busy man is one who finds time to follow his passions, he always used to say,” Lakshmi had told me earlier.

Arvind’s life — and death — is the story of the joys and grief of an entrepreneur’s life. It goes beyond the hype of valuations, battles with dominant investors, and billion dollar listings. It is the story about the sense of immortality that all of us entrepreneurs carry proudly on our shoulders. That works most of the time. But, like in Arvind’s instance, doesn’t sometime.

As Eugene O’Kelly, the late former CEO of consulting firm KPMG wrote in his book, Chasing Daylight: How My Forthcoming Death Transformed My Life: “Confront your own mortality, sooner rather than later.”

Don’t forget to play hard while you work hard, dear founders.