AS CSAM SURGES IN INDIA, A NEW DRIVE TO PROSECUTE OFFENDERS

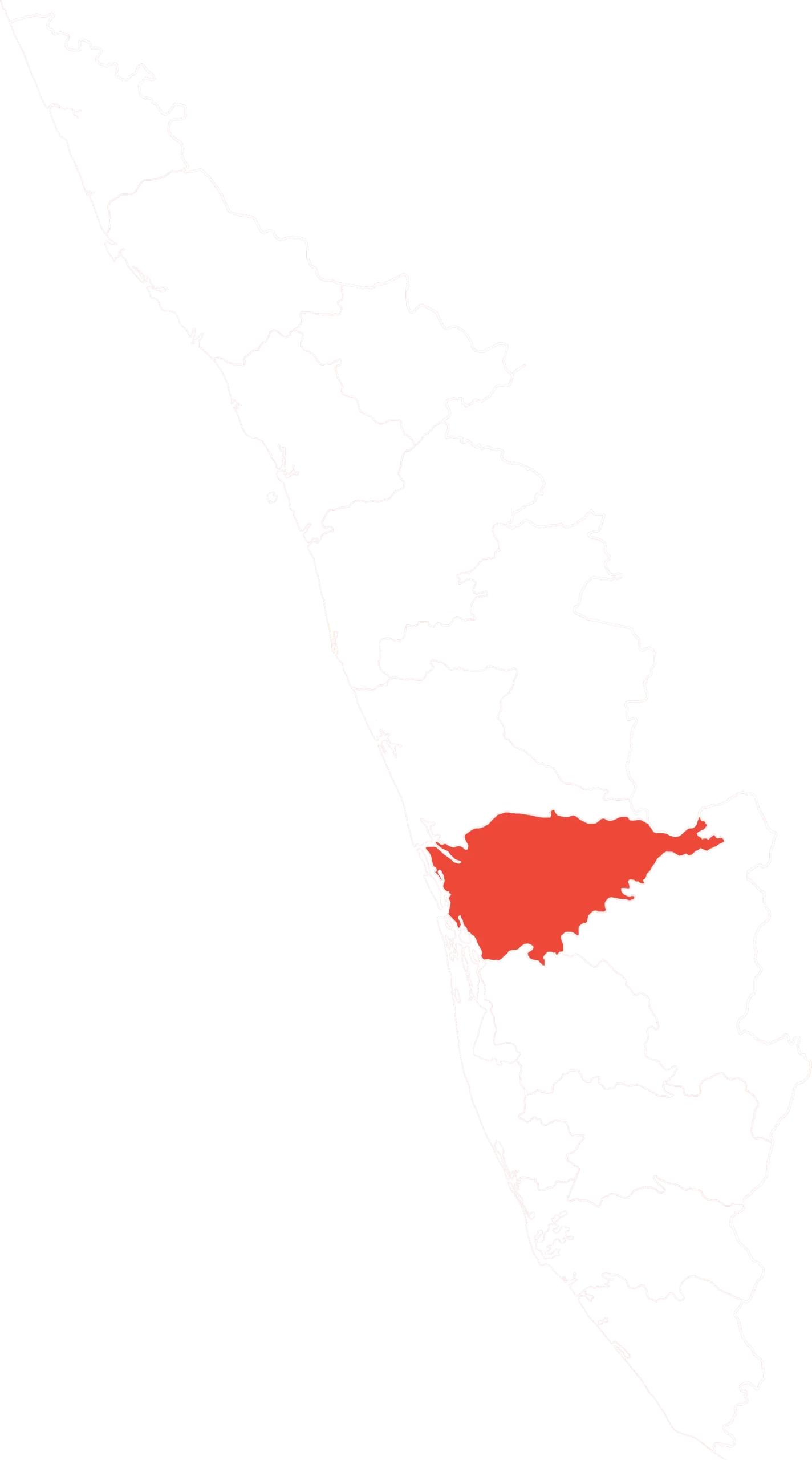

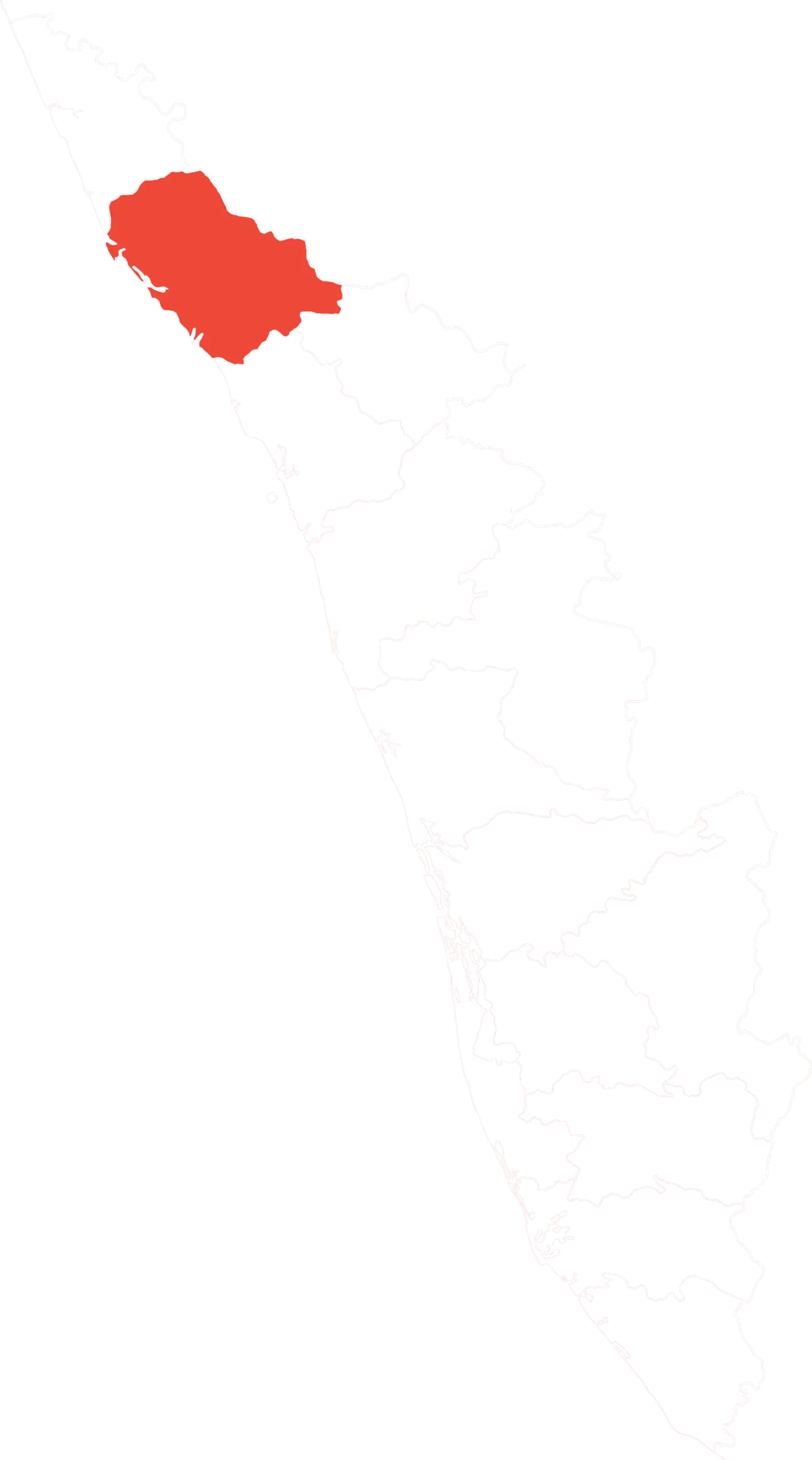

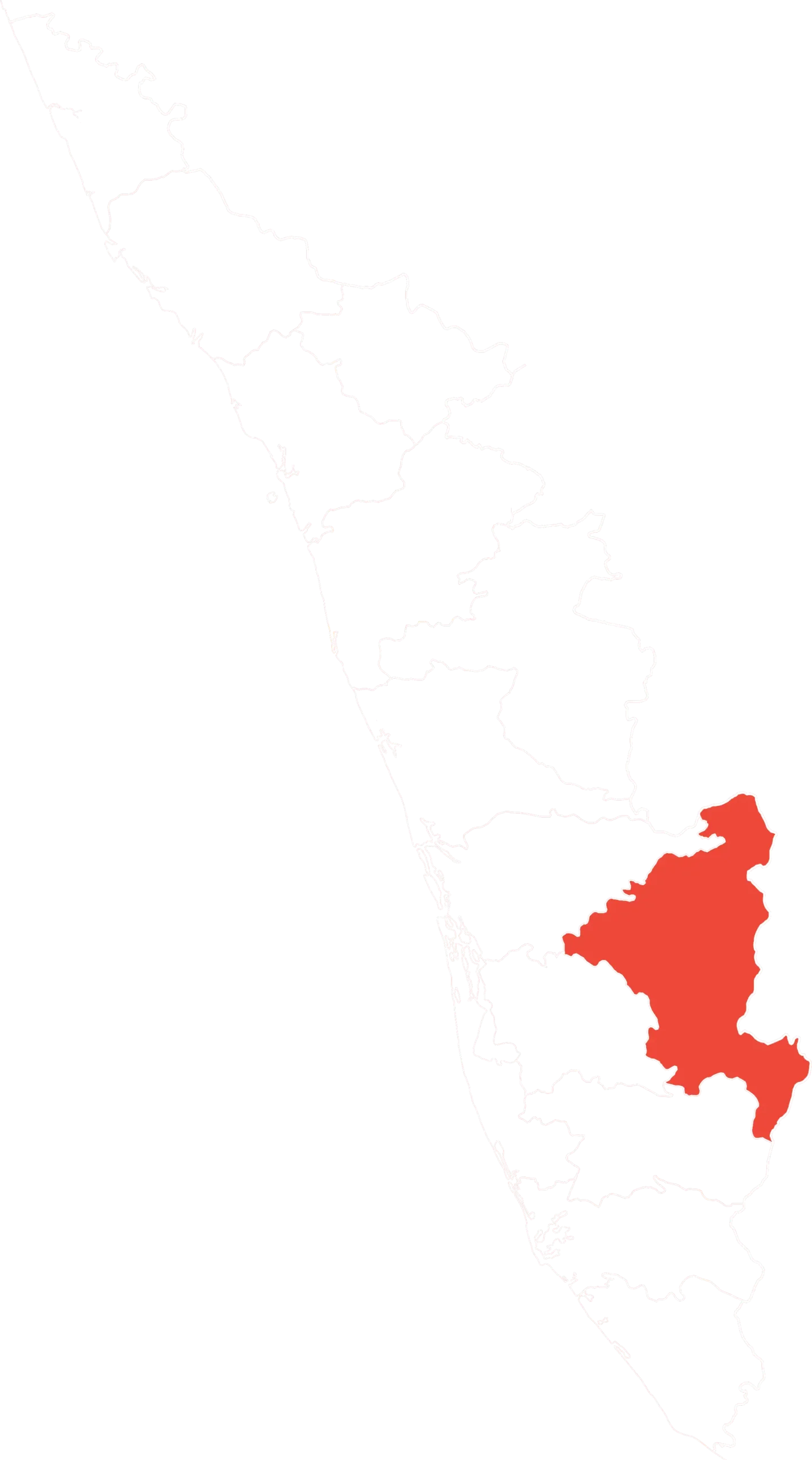

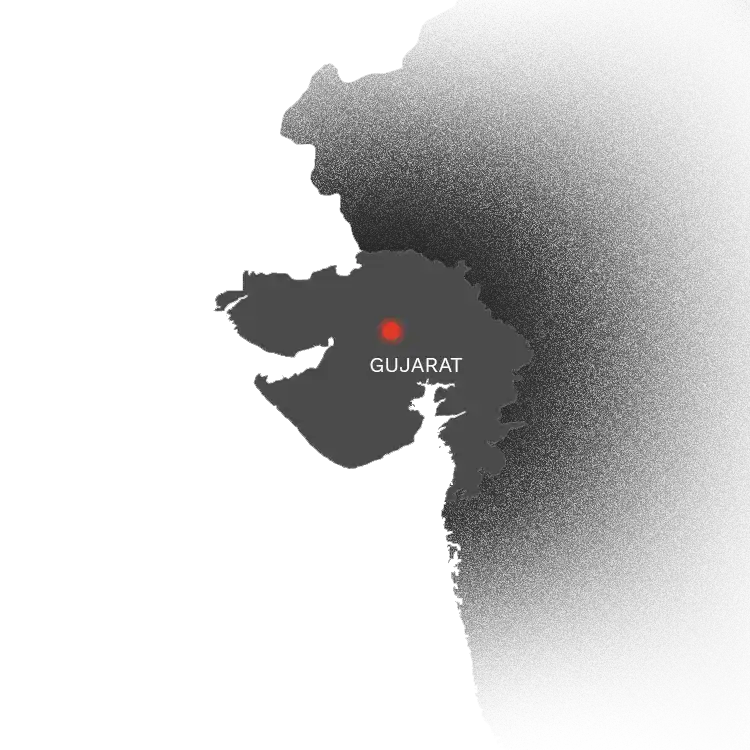

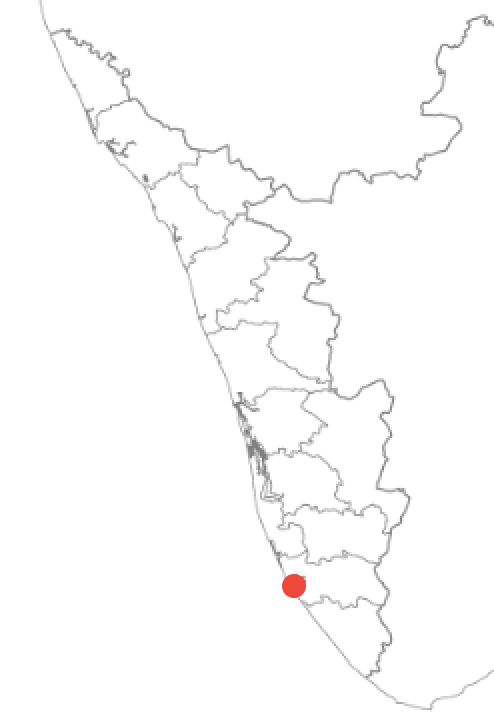

OPERATION P-HUNT 20.1 As dawn broke over the ancient port city of Kollam on June 27, the police team looked up at the passing clouds anxiously. “Not today, please,” was the common thought. It had rained all through Friday. Even during the ‘before times’ of the coronavirus pandemic, the monsoon was never a good time for any large outdoor operation in Kerala.

Some light rain fell, but the rest of Saturday was clear and the Kollam police’s raids across the district to check the tide of Child Sexual Abuse Material (CSAM) went off smoothly. The Kollam raids were part of a state-wide crackdown after police noted a surge in CSAM traffic on the Internet during the lockdown. Incorrectly termed child porn (porn implies consenting adults), CSAM refers to visual material portraying a sexual act involving a child.

The Kollam police teams hit nine addresses. “Nine people had been tracked down for accessing and sharing child porn on [the] Telegram app,” a Kollam City Cyber Cell officer said.

By evening, the Kollam police had picked up nine suspects and taken them to the local police stations for questioning. The various devices seized from the suspects—ranging from mobile phones to laptops and pen drives—were sent for forensic analysis. By the end of the day, the police had registered cases under the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act and the Information Technology (IT) Act against all nine, all men under the age of 25.

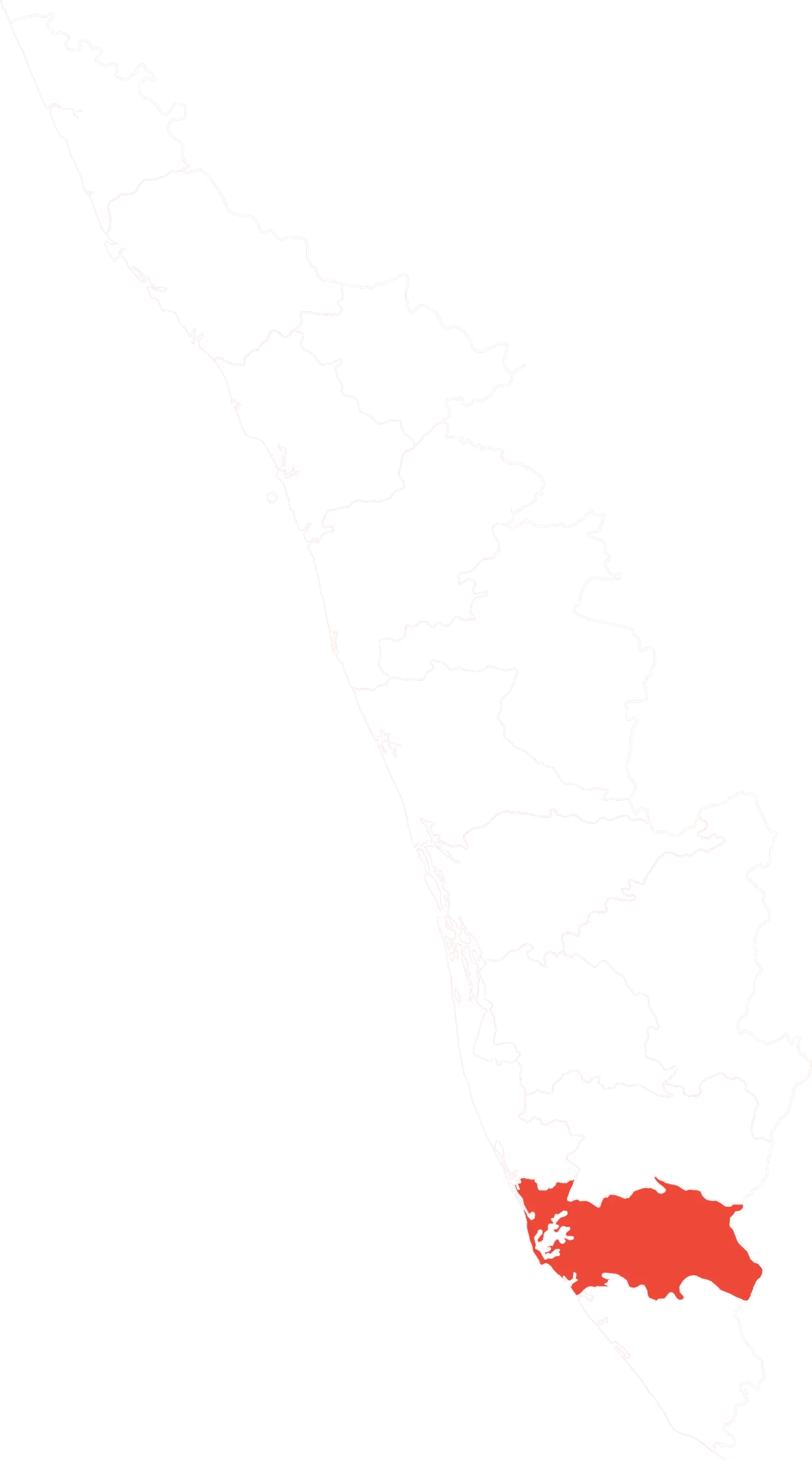

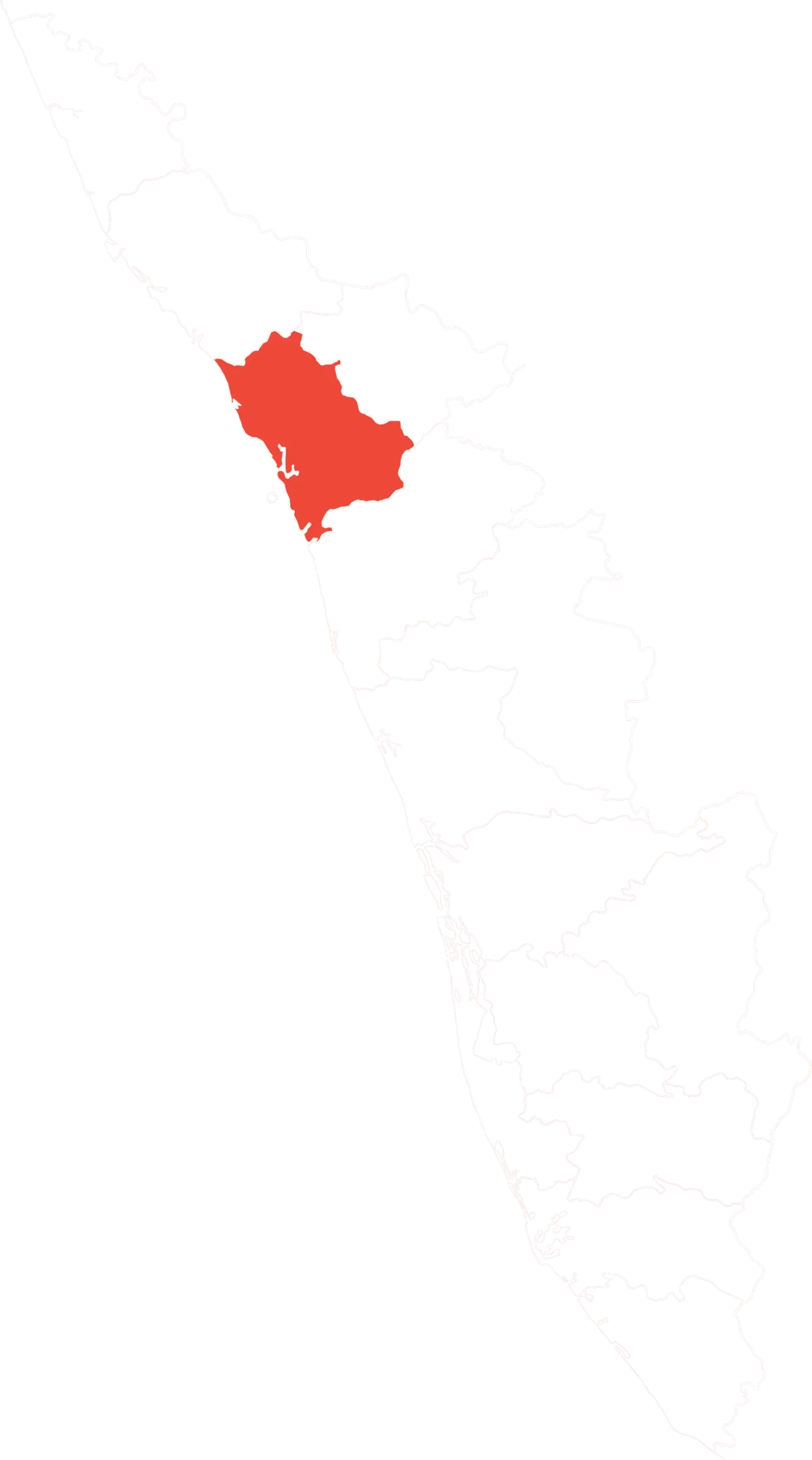

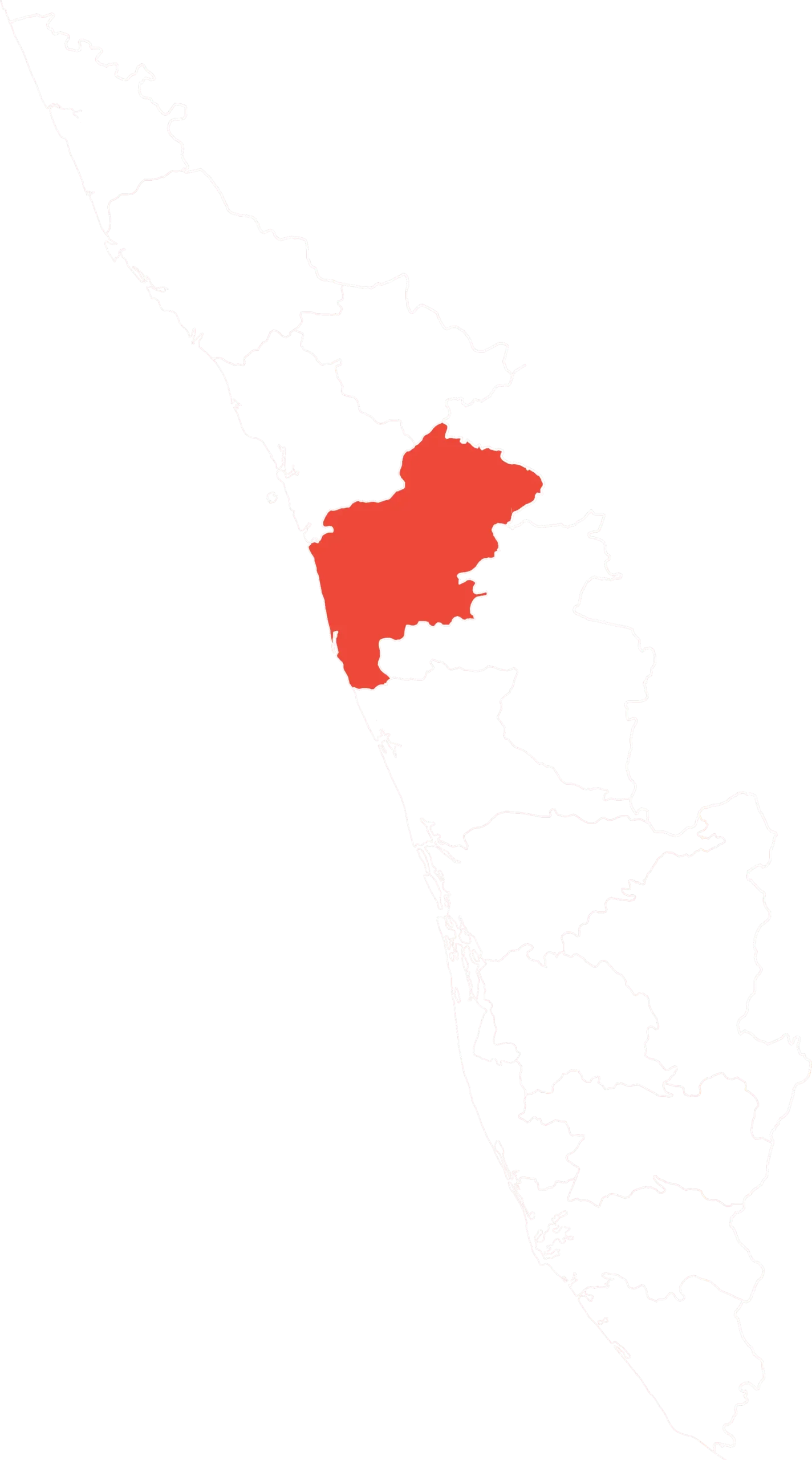

For Kerala police, which has the oldest and most visible operation in India against CSAM, the Kollam operation was the largest in that day’s crackdown, codenamed P-HUNT 20.1. The ‘P’, ostensibly, stood for paedophiles; and the 20.1 for the first operation of the year 2020. Version 1 of the P-HUNT, the first dedicated operation by any Indian police force against CSAM, was organised in 2017.

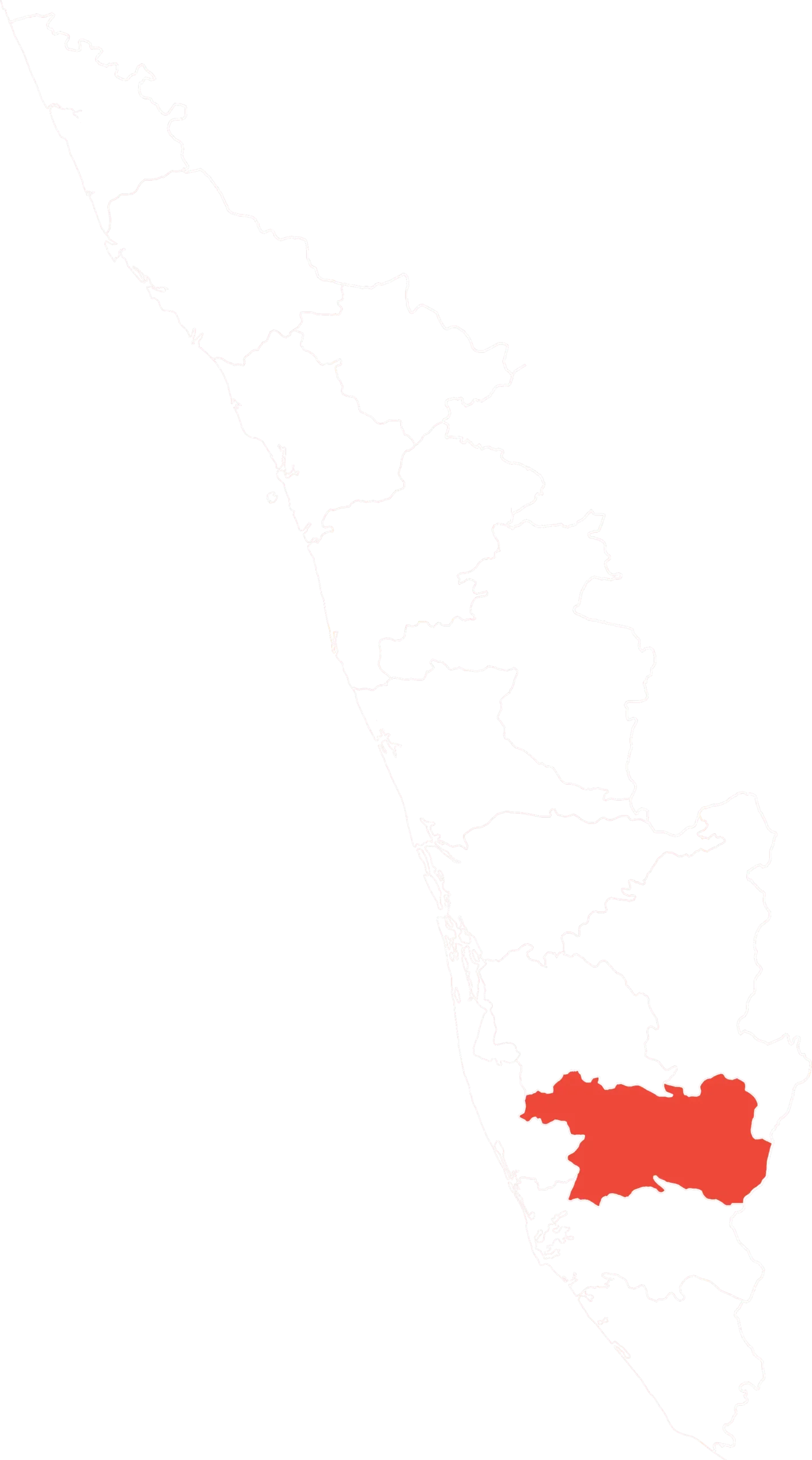

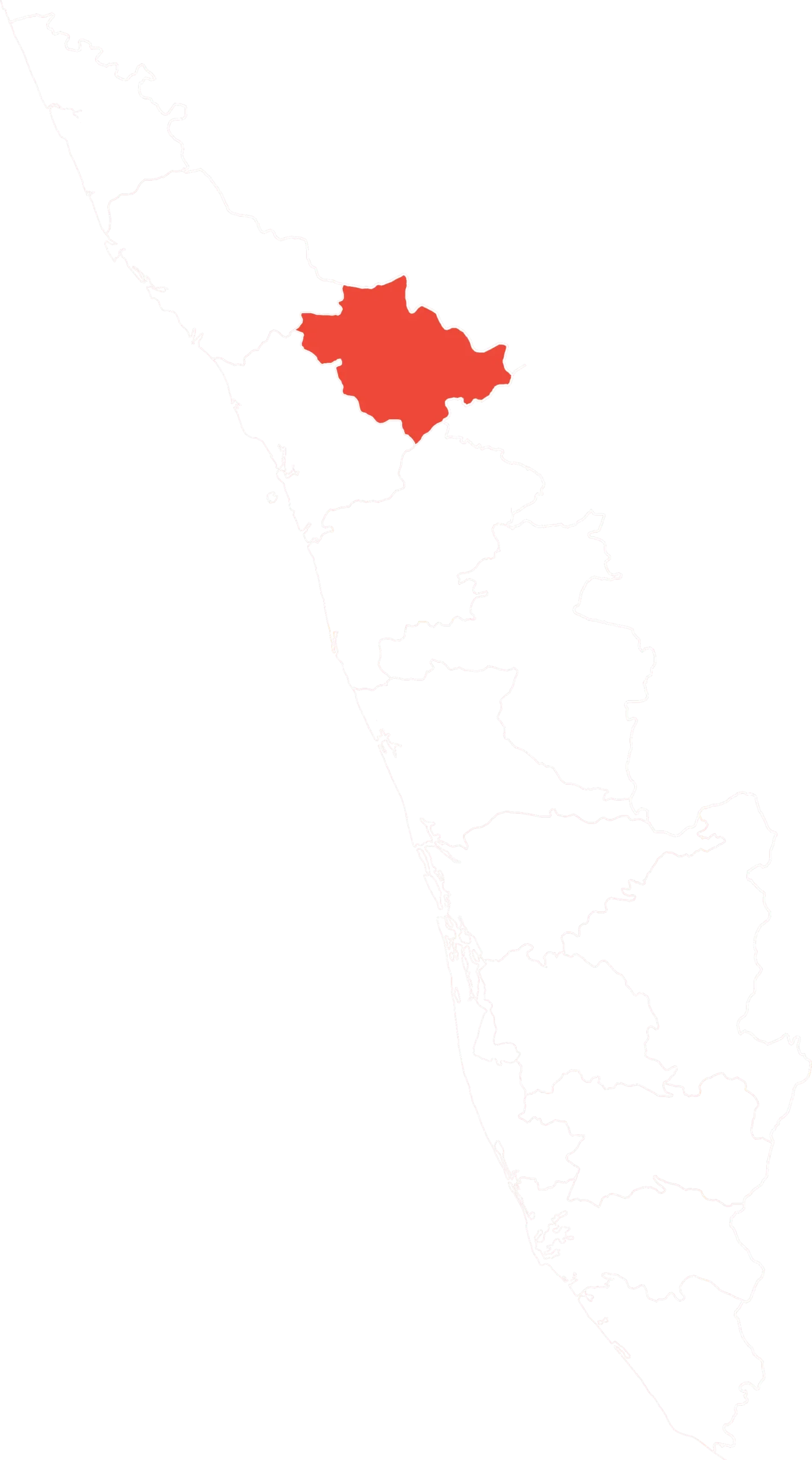

In October 2019, the police had picked up 38 people from 21 places across 11 districts. In April 2019, it had arrested 21 people in a similar raid across 12 districts. This year, in the first week of June, following a tipoff from UNICEF, the United Nations body for children, the police had arrested three people who were members of a WhatsApp group that circulated CSAM.

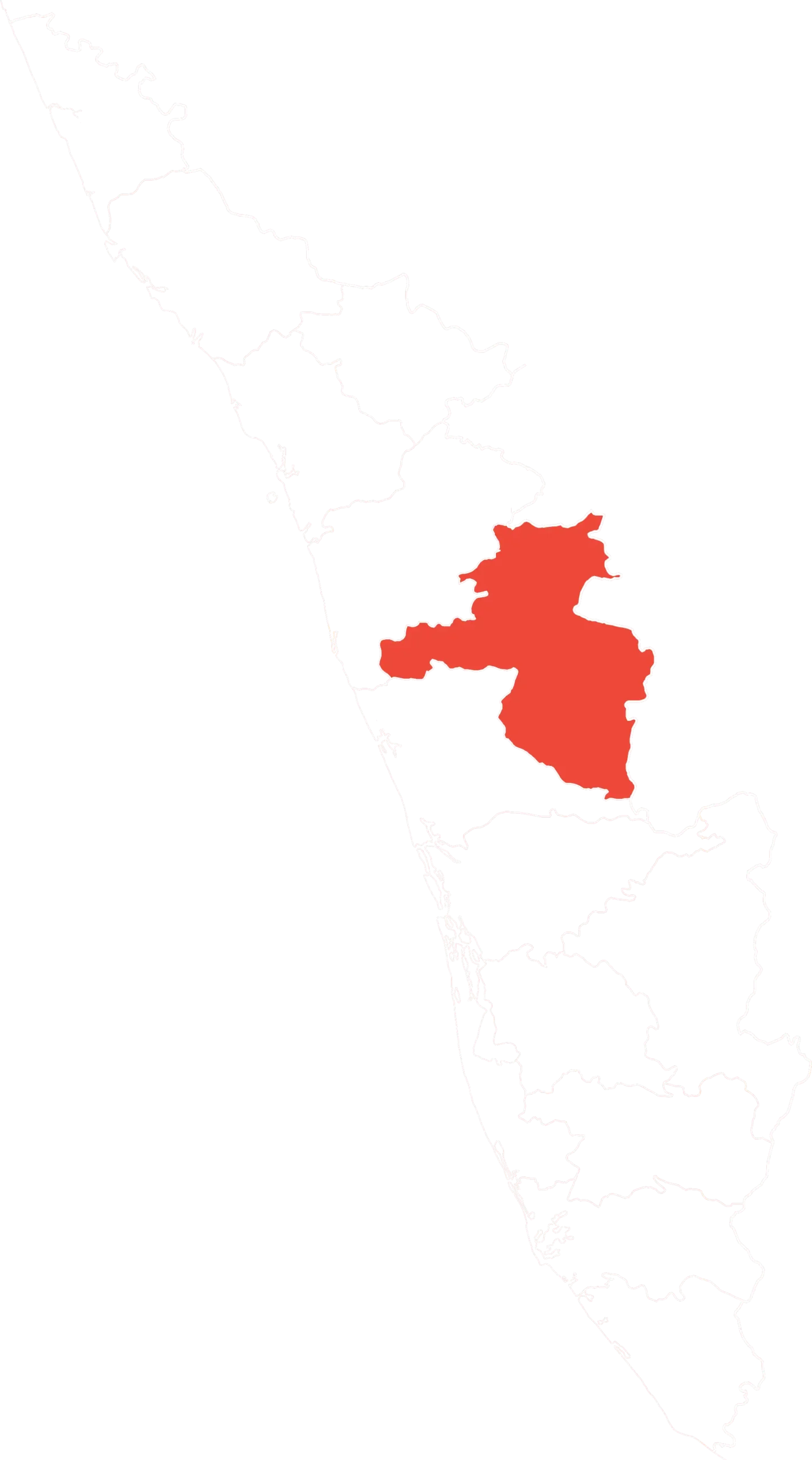

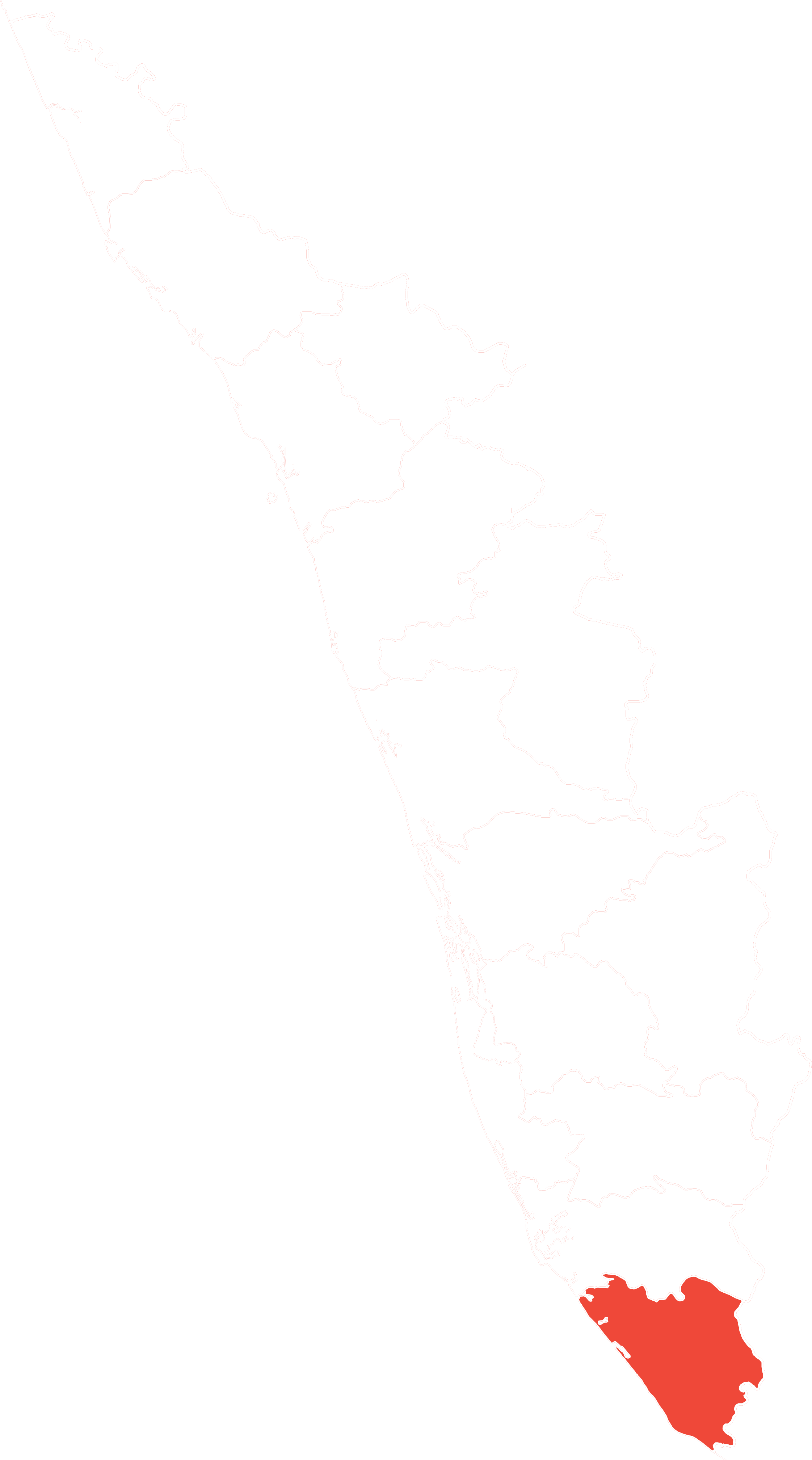

For the June 27 raid, the net was cast wider—Kerala Police formed 117 teams across the state, registered 89 cases and arrested 47 suspects. Not all offenders could be traced or arrested that day. For evidence, it had seized 143 devices, including laptops, mobile phones, modems, hard disks, memory cards, and computers.

“(State Police) Headquarters tightly co-ordinates these raids. They pass on a list of names, addresses, and phone numbers to the district headquarters. And then a date is fixed so that we raid the suspects simultaneously across the state,” says a police officer who took part in the operation. Simultaneous raids are important as the Police try and arrest all the members of a particular WhatsApp or Telegram group, he adds. “Otherwise, members will get tipped off and abscond if we do it one by one”.

The raids were based on information from the Counter Child Sexual Exploitation Centre (CCSEC), India’s first dedicated unit to prevent child sexual exploitation via the Internet, set up in 2019 by Kerala Police.

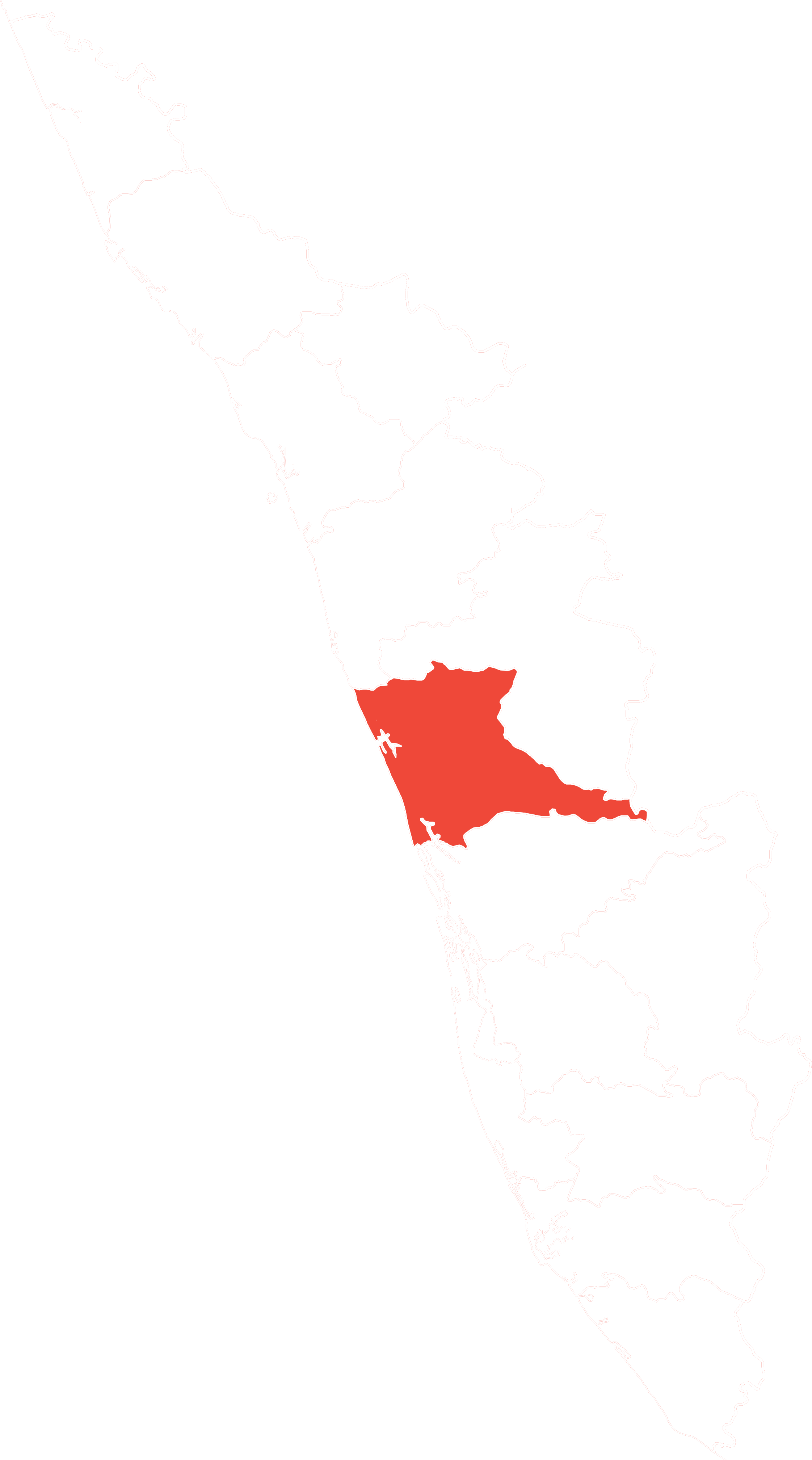

The CCSEC works closely with Interpol, the international criminal police organisation based in France, to collect information on CSAM usage across Kerala. An officer with CCSEC told FactorDaily that Kerala Police has been given access to a portal—the Internet Crimes Against Children and Child Online Protective Services (ICACCOPS)—that allows it to see reports of CSAM usage in Kerala, along with the user’s IP address, date and time of access, the URL of the content, as well as the actual content. “Every few months, we collate all the incidents whose IP addresses are from Kerala. We segregate the information by district, pass it on to district headquarters, and plan a simultaneous raid.”

The International Centre for Missing & Exploited Children (ICMEC), a privately-funded NGO that works with law enforcement agencies, the UN and Interpol, has shown selected officers of Kerala Police how to use special technology tools to track and investigate CSAM.

“(State Police) Headquarters tightly co-ordinates these raids. They pass on a list of names, addresses, and phone numbers to the district headquarters. And then a date is fixed so that we raid the suspects simultaneously across the state,” says a police officer who took part in the operation. Simultaneous raids are important as the police try and arrest all the members of a particular WhatsApp or Telegram group, he adds. “Otherwise, members will get tipped off and abscond if we do it one by one”.

After the Union government imposed the COVID-19 lockdown in end-March 2020, Kerala police began to monitor 11 social media websites including WhatsApp, Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Telegram. But the focus was on two platforms—WhatsApp and Telegram. Some of these groups—named Sreyayude, Thavalam, Manthanga Girl and Thanasertha—had over 200 members each.

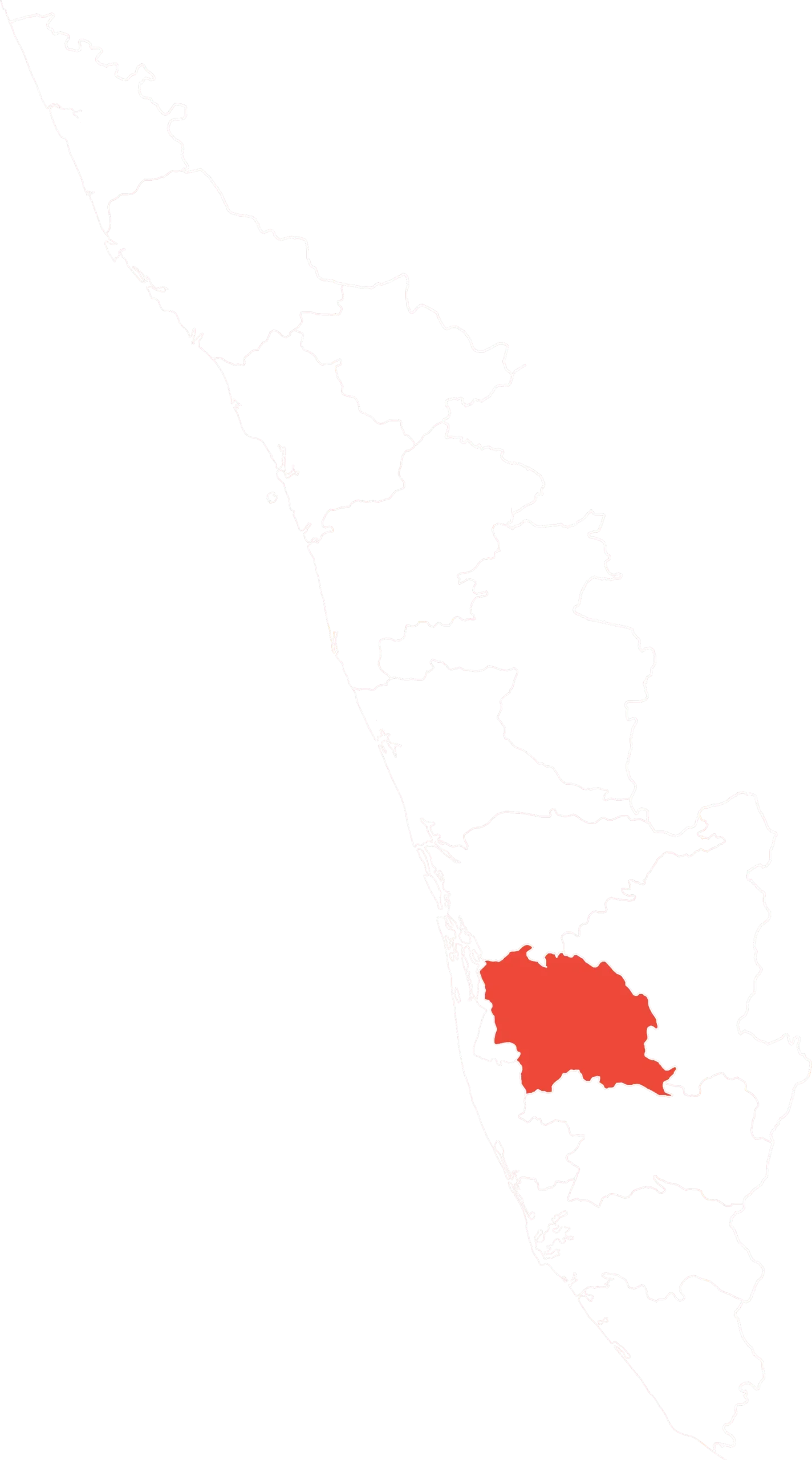

The arrests revealed how consumption of CSAM spanned the spectrum of society. In Idukki, it was a doctor in his early 30s working at a primary health centre, while in Kottayam, it was a hotel management graduate working in West Asia who got stuck in India when he came home and the government announced a sudden lockdown. In Kannur, it was a man in his late 30s who had done a short stint in the Indian Navy and then taken up a job in Abu Dhabi. He had come to Kerala recently.

According to the police, many of those arrested were men in their early 20s. In Kollam, everyone arrested was below 25 years old, including a 16-year-old. In the case of the minor, police officers have said that they will consult mental health experts and send him for counselling.

According to the CCSEC officer, some people had sold CSAM for small amounts of money. “In about three or four cases, the persons involved provided CSAM content in return for money. The sums involved were typically between Rs 25 and Rs 50 and transacted over Paytm or UPI,” he said.

Source: Kerala Police

INDIA AND CSAM

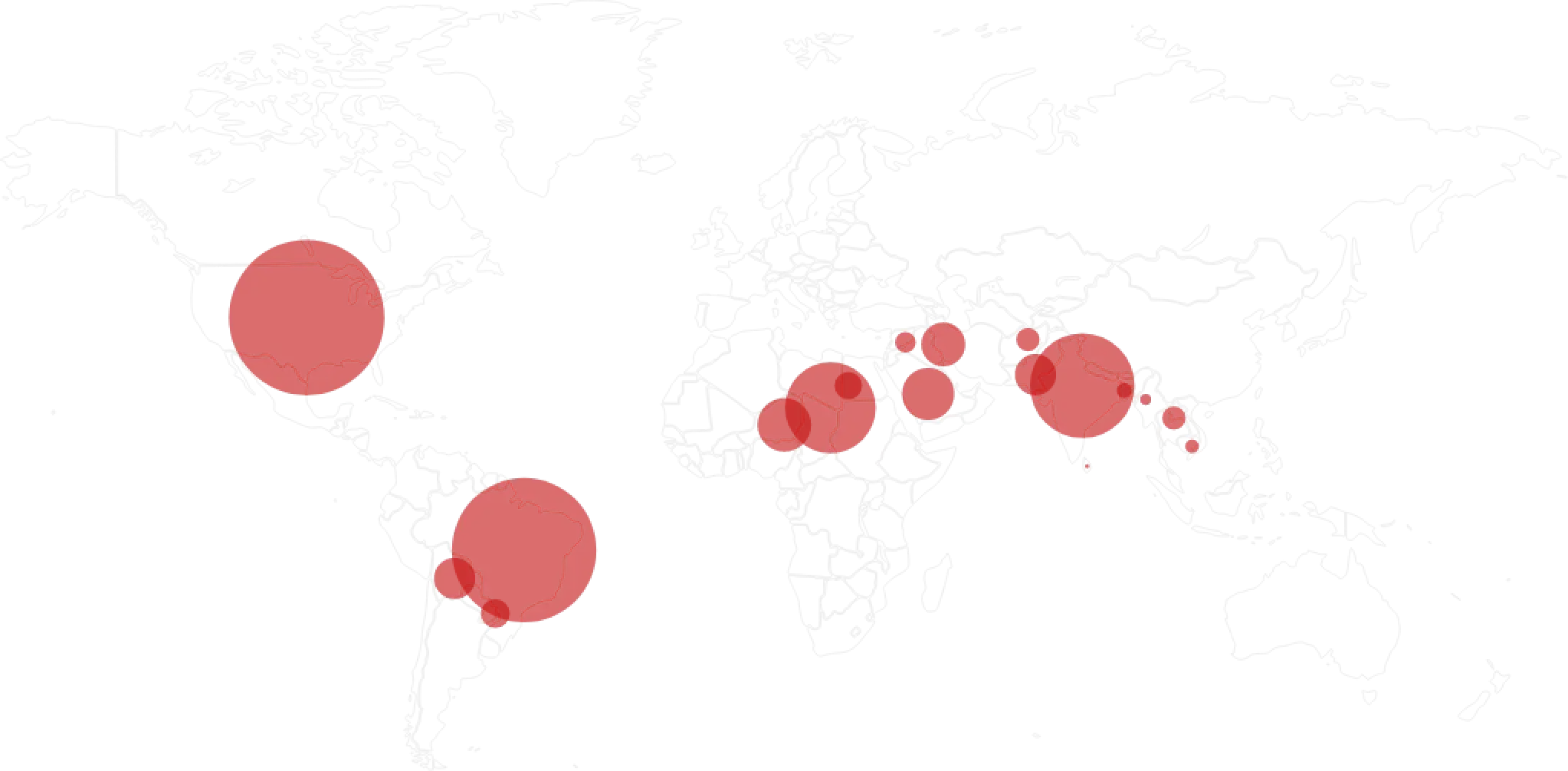

An idea of how much CSAM has flooded Indian cyberspace can be gathered from a 2019 report by the US-based National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC). The Center runs a CyberTipline on which US federal law requires companies such as Facebook, Twitter and Apple to report instances of CSAM on their platforms. Over 1,400 companies have registered with the Cyber Tipline, and their reports are geotagged.

In 2019, the NCMEC got 16.9 million suspected CSAM reports, of which nearly 1.98 million were from India—the single-largest out of 241 countries. The Indian subcontinent ranks high when it comes to CSAM consumption. Pakistan came second with 1.15 million reports and Bangladesh generated more than half a million reports.

Tap on Districts

| Total cases |

| Afghanistan 163,120 |

| Algeria 700,535 |

| Bangladesh 556,642 |

| Brazil 398,069 |

| Burma/Myanmar 233,681 |

| Colombia 264,582 |

| Egypt 276,596 |

| India 1,987,430 |

| Iraq 1,026,809 |

| Jordan 123,537 |

As far as companies go, Facebook (which includes WhatsApp and Instagram) sent 93 per cent of the tips (15.8 million out of 16.9 million reports worldwide). Google nearly 450,000 and Microsoft 123,000. Snapchat reported 82,000 cases and Twitter 45,000.

There are several caveats. For one, the use of proxies and anonymisers distorts and undercounts the numbers in many countries. The NCMEC report also notes that 1.6 million reports don’t mention the country for reasons such as no IP address or proxy IPs.

Then, reports by companies also depend on their infrastructure for detecting CSAM. Facebook has invested considerably in CSAM detection, which is why it accounts for more than 90 per cent of CSAM reports. At the other end, while websites such as 4chan and 8chan have a long history of easy availability of CSAM, they have reported very few cases to NCMEC.

HISTORY OF CSAM PROSECUTION IN INDIA

2008

India had been considering laws against CSAM since the 1990s. The Information Technology Act, which was passed in 2000, was aimed at giving legal recognition to electronic commerce and checking cybercrime. It was only in 2008 that the first legal provisions to prosecute CSAM were passed, when the IT Act 2000 got Section 67(B). Under this, publishing or transmitting CSAM can land you in jail for up to seven years.

Information Technology Act

CRIMES

- Publishing or Transmission of images of children in sexually explicit act or conduct.

- Creating, collecting, seeking, browsing, downloading, advertising, promoting, exchanging or distributing CSAM.

- Cultivating, enticing or inducing children into an online relationship

- Facilitating the abuse of children online

- Recording electronically any sexually explicit act with children

PUNISHMENT

- First conviction: Up to 5 years imprisonment and up to Rs 10 lakh fine.

- Subsequent conviction: Up to 7 years imprisonment, and up to Rs 10 lakh fine.

2012

More laws against CSAM came in 2012 when Parliament passed the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act. While the IT Act focuses on prosecuting offenders for accessing CSAM, the POCSO Act cracks down on the use of children for producing CSAM, among other things.

POCSO Act

- Using a child for pornographic purposes—up to five years sentence for the first offence, and seven years for the subsequent offence.

- Participating in pornographic acts with a child will be punishable according to the remaining provisions of POCSO Act.

- Storing pornographic material involving a child will be punishable with up to three years sentence.

2019

In 2019, India amended the POCSO Act to distinguish possession of CSAM into three categories. For possessing and failing to report; for transmitting; and for commercial purposes.

POCSO Act 2019 AMENDMENT

- Storing CSAM but failing to delete or destroy or report to the police, will attract Rs 5,000 for the first offence, and Rs 10,000 for subsequent offences.

- Storing CSAM for transmission will be punishable with up to 3 years in jail.

- Storing CSAM for commercial purposes will be punishable by jail time of 3 to 5 years for the first conviction, and 5 to 7 years for subsequent convictions.

India’s laws against CSAM are comprehensive, says A Nagarathna, a legal scholar who heads the Advanced Centre on Research, Development and Training in Cyber Laws and Forensics at the National Law School of India University, Bengaluru.

“But the implementation is completely lacking,” she says.

The numbers back her. The NCMEC recorded nearly 2 million instances of access to CSAM from India in 2019 alone. But the National Crime Records Bureau’s data show that we are prosecuting a tiny fraction of this.

Consider the IT Act, which prosecutes the publishing of CSAM under Section 67(B). NCRB started collecting data on cybercrime since 2014 and has data on prosecuting CSAM from 2014 till 2019.

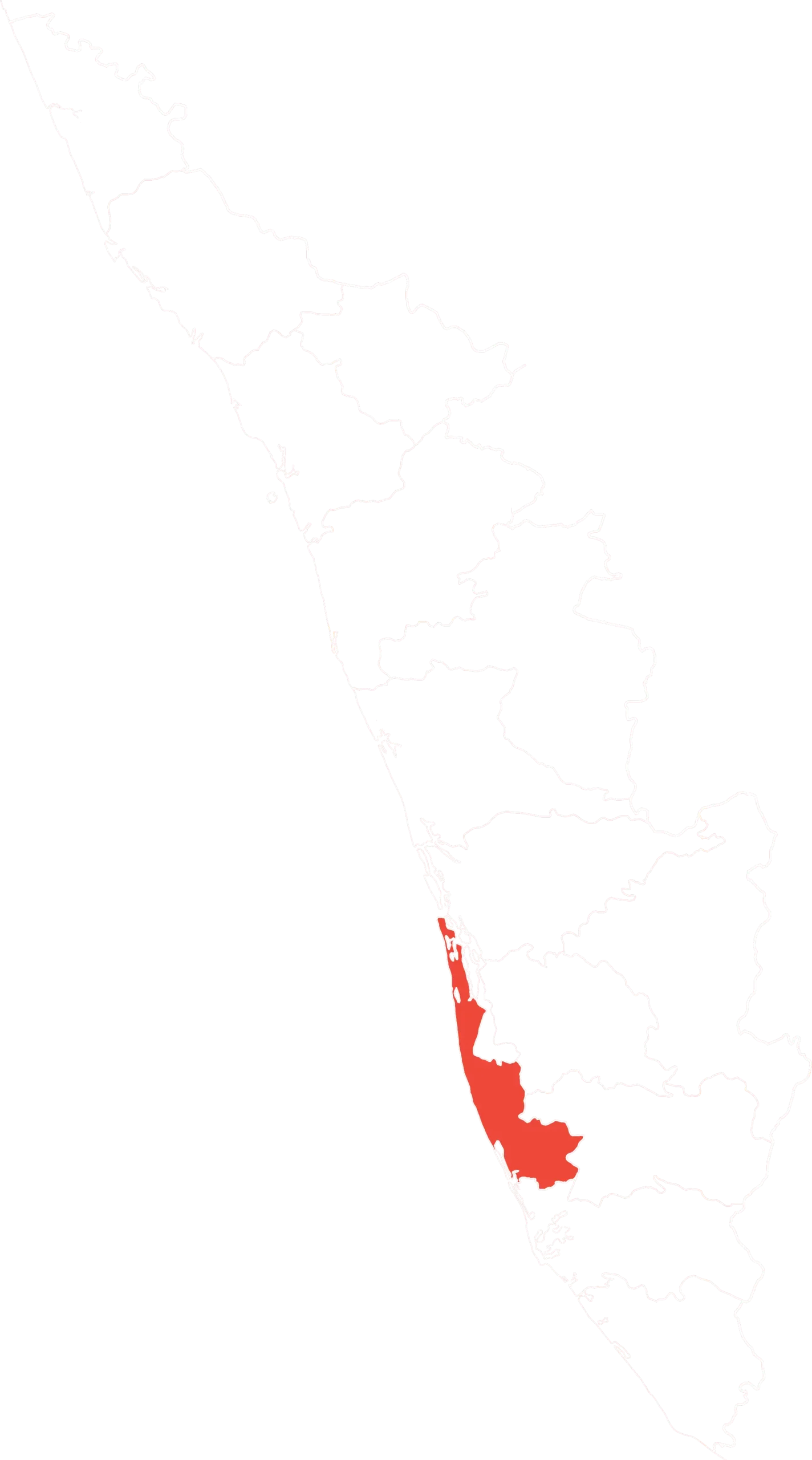

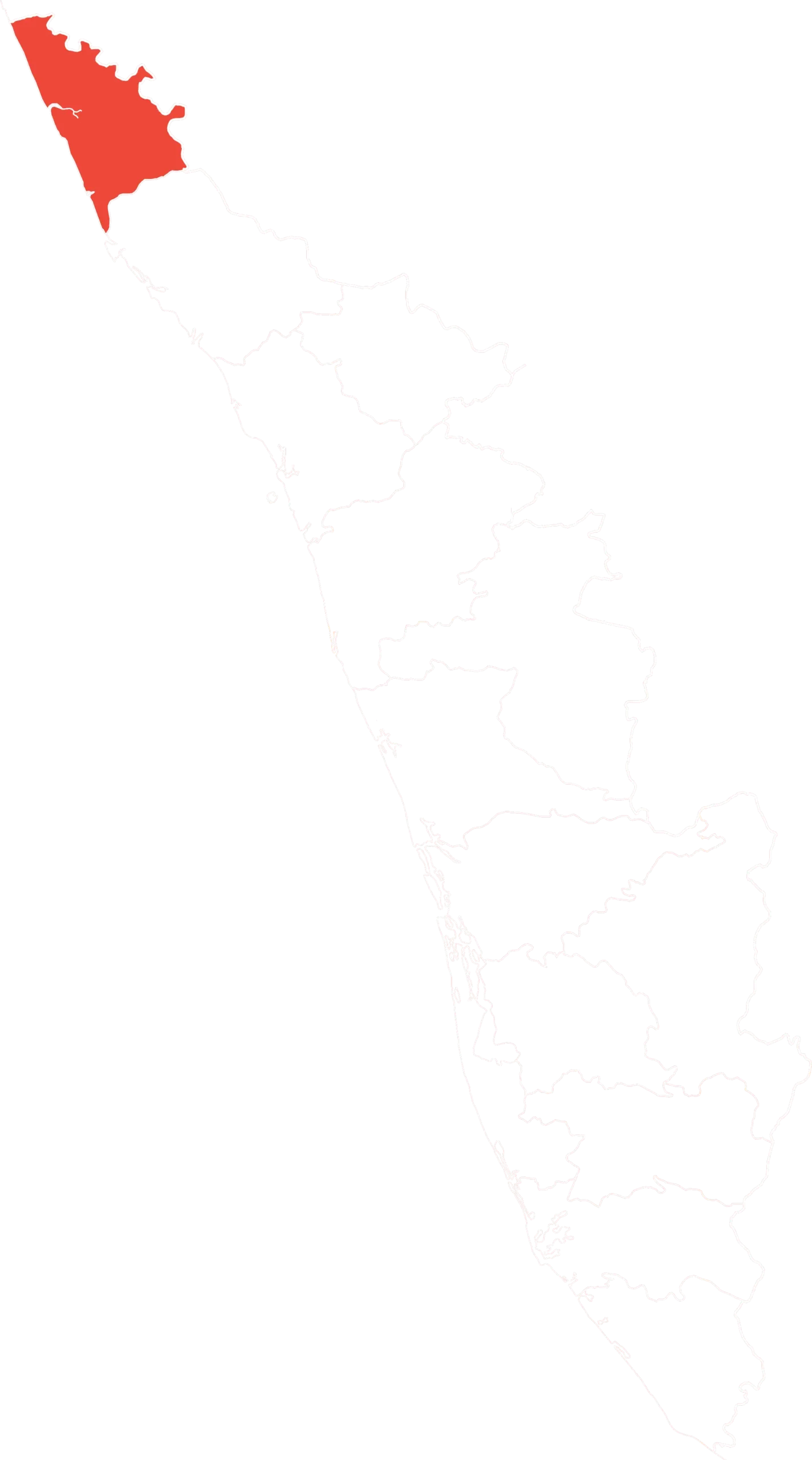

Only five and eight cases were filed in 2014 and 2015 respectively under Section 67(B). Since then, numbers have increased—17 cases were filed in 2016, 46 in 2017, and 82 in 2018. In 2019, 102 cases were registered under Section 67(B), with Kerala(27) and Uttar Pradesh(25) accounting for half of these cases.

More shockingly, the police in the 19 metropolitan cities filed only 15 of these cases in the four years between 2016 and 2019. Delhi accounts for six of these, while Bengaluru, Chennai, and Mumbai have filed two cases each.

Police have filed charge sheets for 120 of the 260 cases across India between 2014 and 2019, a follow-up rate of 46 pc. But at the courts, CSAM convictions turn into a trickle.

In the six years between 2014 and 2019, trials were completed in only eight cases: Six people have been convicted in these cases. By the end of 2019, the courts had a pendency percentage of 98.8 pc for cases filed under the IT Act to prosecute CSAM.

The POCSO Act has seen more prosecutions than the IT Act—between 2014 and 2019, 2481 cases have been filed under Section 14 and Section 15 of the Act.

In particular, the last few years have seen a significant drive to register more cases, with 374 cases in 2017, 812 cases in 2018, and 1114 cases in 2019. Odisha leads in registered cases with 885 cases, followed by Bihar (368), Rajasthan, Kerala, and Jharkhand.

But, just as in IT cases, our biggest cities have seen very few prosecutions. Of the 2,347 cases filed from 2016-2019, only 87 of these were filed in the largest 19 metros. Jaipur alone accounts for more than half with 27 cases. Hyderabad filed no cases in these four years, while Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata, Chennai, and Bangalore filed 42 cases altogether.

POCSO SECTION 14 and 15

(2014-2019)

Source: National Centre for Missing and Exploited Children

Once POSCO cases are registered, the police have largely been prompt in filing charge sheets. Between 2014 and 2019, over 80 per cent of FIRs were converted into charge sheets.

But it is at the courts where prosecution gets stuck. Between 2014 and 2019, out of 1,777 cases that were pending trial, only 295 cases could be decided: 129 cases resulted in convictions while 164 resulted in acquittals.

The NCRB data on trafficking also classifies cases where children have been trafficked under the head of “Child pornography”. Between 2016 and 2019, 316 such cases have been recorded in Karnataka, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, and Rajasthan.

“Whether it is the POCSO or IT Act, cases registered are quite low,” the NLSIU’s Nagarathna says.

There are many reasons behind this—reluctance to register cases, cases not being reported and so on. “When it comes to any cybercrime including this, we hardly have any police officers who take it seriously. Unfortunately, for child sexual abuse, they should be more proactive. But it remains the same,” she says.

According to Nagarathna, police officers need training in handling digital evidence. “We have done a lot of sensitisation programmes for Special Juvenile Police units on sexual offences. But this training does not cover online sexual offences,” she says.

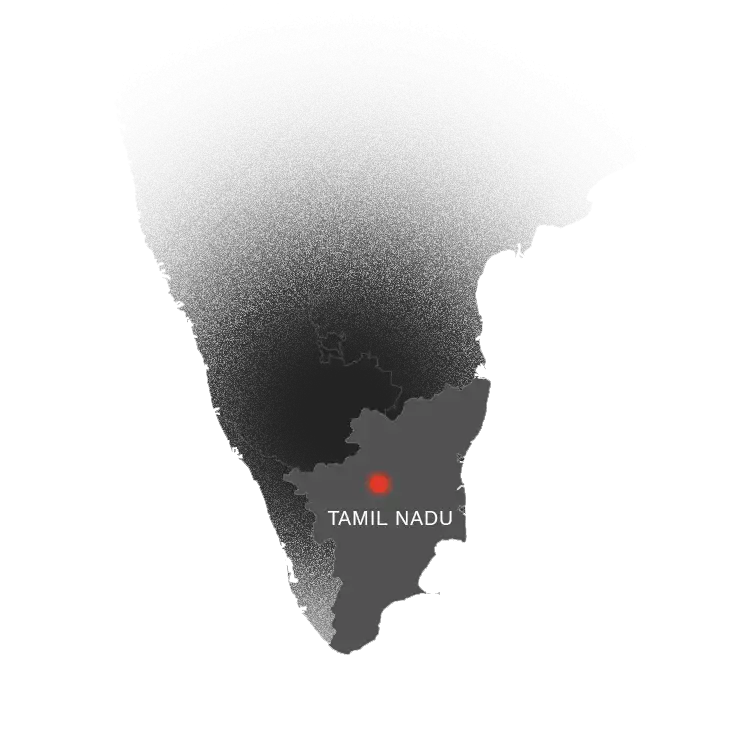

What the NCRB data does not show is how widespread the problem is in India. Vidya Reddy, the Founder-Director of the Chennai-based NGO Tulir – Centre for the Prevention and Healing of Child Sexual Abuse, says that consumption of CSAM happens across class and geographies.

Reddy had participated in the drafting of the 2008 amendment to the IT Act, which criminalised possession of child sexual images.

She cites how a case filed by Tulir in 2015 against a Tamil Facebook group showed that the problem was widespread. This group posted everyday pictures of kids doing normal things such as eating ice-cream, playing in the park, accompanied by Tamil text, transliterated in English, asking “Enna Pannla”—“What should we do?”

“What followed was the most violently graphic sexual comment from people,” says Reddy. “There were 3,000 people commenting on a picture. And those 3,000 people obviously see an eight-year-old eating an ice-cream in a very sexual way,” she said. Reddy says that when a complaint was raised with Facebook, the company responded that the text was not considered as an obscenity by the community guideline moderators working in English.

So, Tulir filed a case against the Facebook page and the police arrested not just the administrator but also went after others. “When they did arrest some of the guys who made the comments, they were your average Joes,” she says. “There was the guy next door, there was a fellow who worked at a Kirana shop, there was a stockbroker, there was a courier delivery guy. They were not just from Tamil Nadu, but from all over the world, not restricted to any geographical part.”

THE TIPPING POINT: CSAM PROSECUTION GETS A BOOST

This mismatch between CSAM consumption and prosecution in India would change only in 2018 with the introduction of a bill in the United States.

In the US, the NCMEC runs CyberTipline, a centralised mechanism that the public, as well as electronic service providers (ESPs) such as Facebook and Google can use to report CSAM. The ESPs account for nearly 99 per cent of the reports. The NCMEC reviews each tip and then forwards it to US law enforcement agencies for investigation.

On December 12, 2018, President Trump signed into law the CyberTipline Modernization Act of 2018, which allowed the CyberTipline to forward tips to foreign law enforcement agencies approved by the US government. Importantly, foreign law enforcement agencies would have access to tips on CSAM from companies based in the US.

In India, matters moved rapidly. By February 2019, the Union Cabinet approved access to Tipline reports from NCMEC to prosecute offenders. On April 26, 2019, a little over four months since the law was passed in the US, the NCMEC signed an agreement with the NCRB, giving the Indian agency access to CyberTipline reports.

The NCRB would also be able to share these reports with law enforcement agencies across India. Access to the Tiplines comes with a few restrictions—the Tipline has to be accessed on a standalone computer through a VPN, and tipline reports cannot be shared with anyone other than law enforcement agencies.

This NCMEC deal helped Indian police departments enforce the IT Act. One of the reasons that only a handful of cases under the IT Act have been recorded is that the Indian government has no jurisdiction over the servers run outside India by companies such as Facebook, Google, Twitter, and Telegram. With the NCMEC deal, the government has found a way to circumvent this when it comes to CSAM content. Now, ESPs like Facebook, Google, and Microsoft report to NCMEC, and they in turn forward these reports to NCRB.

The Indian government has also beefed up the laws to prosecute CSAM. In July 2019, Parliament passed an amendment to the POCSO Act which, among other things, promises more stringent punishments on CSAM. For using children for pornographic purposes, jail was set to a minimum of five years. This could go up to life imprisonment or death if aggravated penetrative sexual assault had happened.

The amendment also increased the punishment for storage of pornographic material to five years. It included two offences. One, failing to destroy, delete, or report CSAM. Two, transmitting, displaying, and distributing such material. In March 2020, the government notified the updated POCSO Rules 2020, making these new amendments effective from March 9.

The sum of these actions has been an unprecedented surge in prosecutions across the country. By March 2020, the NCRB had shared 32,719 NCMEC CyberTipline Reports. The NCRB says more than 182 FIRs have been filed (many states have not yet set up the specialised units, and those that have done so are yet to get going).

Even the CBI has got into the act. It has set up a special unit—the Online Child Sexual Abuse and Exploitation Prevention/ Investigation (OCSAE) unit — to investigate CSAM.

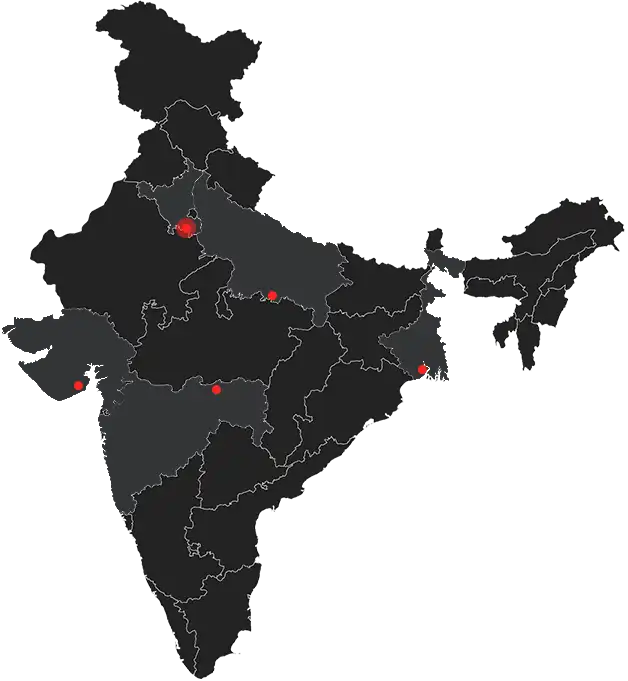

In October 2019, based on a tipoff from the German Embassy, the CBI booked cases against seven people in Delhi, Tamil Nadu, Haryana, West Bengal, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh. These arrests were based on the conviction in Germany of Sascha Treppke who was a member of 29 WhatsApp groups that shared CSAM. Seven people from India were also members of these groups. The OCSAE unit also booked a Delhi-based firm for hosting websites with CSAM content on servers based in Russia.

In November 2019, Women and Child Development Minister Smriti Irani informed Parliament that 377 websites had been taken down for hosting child sexual abuse material.In the first week of October 2020,the Kerala Police completed Operation P-Hunt 20.2, the second simultaneous raid across the state for prosecuting CSAM. This raid saw 41 persons arrested for accessing CSAM on WhatsApp and Telegram. A press release from the Kerala Police stated “There is still heightened online activity seen from Kerala by those seeking child abuse material on the net, and particularly the dark net.”

CASES RISE BUT SOME TAKE YEARS TO FILE

While there has been an improvement in filing cases, there is still a question mark on successful conviction, given the poor record of the courts. Long delays in filing charge sheets are common as a result of long turnaround times for analysing phones by Forensic Science Laboratories (FSL) . Additionally, difficulty in obtaining information from servers located outside India has led to poor conviction rates in cases under the IT Act.

One reason is that the confiscation of digital evidence continues to be a challenge for investigating agencies. “We are talking about evidence from computers, mobile phones, servers, and ISPs. Often the content is uploaded on platforms like Google or Facebook who are not based in India,” says NLSIU’s Nagarathna.

Under The Code of Criminal Procedure, the Investigating Officer has to write to a local magistrate, who, in turn, forwards the request to the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI). The CBI scrutinizes the application. A lot of cases are rejected at the vetting stage. If it makes through this stage, it is marked to the ministries of External Affairs and Home Affairs. The Ministries then forward it to the diplomats of the country where the server is located. Once the request reaches the host country, it has to be processed through a similar stack in reverse: justice department, a local magistrate, local police, and then the company that hosts the server.

“Cracking a case during investigation is different from getting a successful conviction during prosecution.” The evidence in such cases are often intangible, or very technical. “Requiring the same burden of proof in a child sexual abuse case, compared to that of a conventional crime, makes it difficult,” she says.

At the same time, Nagarathna says, we need to focus as much on blocking content as on prosecution. “We are trying to focus more on finding the offender and punishing the offender. But the offending content continues to live in cyberspace,” she says. “That adds more to the psychological trauma of the victim.” India needs an approach that focuses on immediately blocking the content, as well as prosecuting the offender.

Take Kerala, which has been the most aggressive state in pursuing CSAM cases in India. In 2015, a Facebook page titled ‘Kochu Sundarikal’ (Little Beauties) was shut down: It featured normal pictures of young girls but had extreme sexual comments. Kerala police took four years to file a charge sheet as it had to gather information from Facebook, whose servers are outside their jurisdiction. It is yet to be seen if the new MoU speeds up collecting evidence for CSAM related crimes.

The other big question is about the children—the victims of CSAM. A large percentage of CSAM content flowing through social media is of South Asian origin. Yet, the government does not have any policy to deal with identifying the children featured in these photographs and videos.

A related question is if this surge in online child abuse images can lead to actual physical sexual abuse of children. According to Tulir’s Vidya Reddy, there is a lot of evidence that points to this direction. “A lot of evidence-based research has shown that there is a high correlation between people who view child sexual images and those who make physical contact with children,” she says.

US clinical psychologists Michael Bourke and Andres Hernandez made waves in 2009 with a study that showed how most CSAM offenders had also committed child sex offences physically. The study, which covered 155 men convicted of possessing child sexual images in North Carolina, found that 85 per cent admitted to having sexually molested a child at least once. On average, each offender had abused 13.5 victims.

“There’s a whole bunch of material out there which helps people rationalise that what they are interested in is perfectly legitimate and normal,” says Reddy. “It definitely gives impetus for a person to go out and abuse.”

“The bigger problems of missing children and child abuse that happens on the ground are more difficult to tackle,” said Rajput. None of these cases has been reported by victims so it’s difficult to identify or rescue the victim in these cases. This drive is aimed to deter the transmission of CSAM that happens through social media on digital devices, he said.